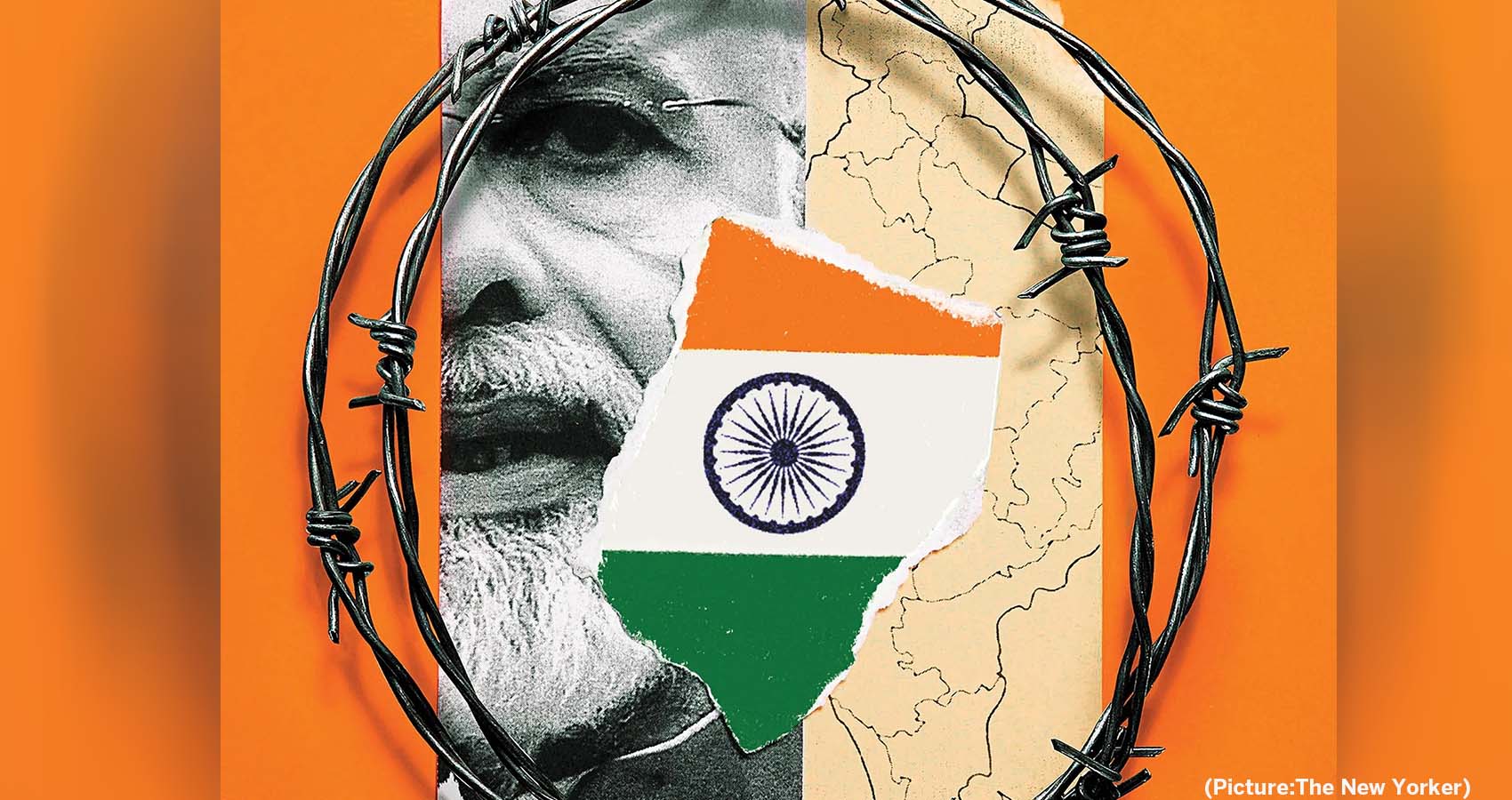

This spring, India is scheduled to hold its 18th general election. Surveys suggest that the incumbent, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is very likely to win a third term in office. That triumph will further underline Modi’s singular stature. He bestrides the country like a colossus, and he promises Indians that they, too, are rising in the world. And yet the very nature of Modi’s authority, the aggressive control sought by the prime minister and his party over a staggeringly diverse and complicated country, threatens to scupper India’s great-power ambitions.

background, Modi dominates the Indian political landscape as only two of his 15 predecessors have done: Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister from Indian independence in 1947 until 1964, and Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, prime minister from 1966 to 1977 and then again from 1980 to 1984. In their pomp, both enjoyed wide popularity throughout India, cutting across barriers of class, gender, religion, and region, although—as so often with leaders who stay on too long—their last years in office were marked by political misjudgments that eroded their standing.

Nehru and Indira Gandhi both belonged to the Indian National Congress, the party that led the country’s struggle for freedom from British colonial rule and stayed in power for three decades following independence. Modi, on the other hand, is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which spent many years in opposition before becoming what it now appears to be, the natural party of governance. A major ideological difference between the Congress and the BJP is in their attitudes toward the relationship between faith and state. Particularly under Nehru, the Congress was committed to religious pluralism, in keeping with the Indian constitutional obligation to assure citizens “liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship.” The BJP, on the other hand, wishes to make India a majoritarian state in which politics, public policy, and even everyday life are cast in a Hindu idiom.

Modi is not the first BJP prime minister of India—that distinction belongs to Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who was in office in 1996 and from 1998 to 2004. But Modi can exercise a kind of power that was never available to Vajpayee, whose coalition government of more than a dozen parties forced him to accommodate diverse views and interests. By contrast, the BJP has enjoyed a parliamentary majority on its own for the last decade, and Modi is far more assertive than the understated Vajpayee ever was. Vajpayee delegated power to his cabinet ministers, consulted opposition leaders, and welcomed debate in Parliament. Modi, on the other hand, has centralized power in his office to an astonishing degree, undermined the independence of public institutions such as the judiciary and the media, built a cult of personality around himself, and pursued his party’s ideological goals with ruthless efficiency.

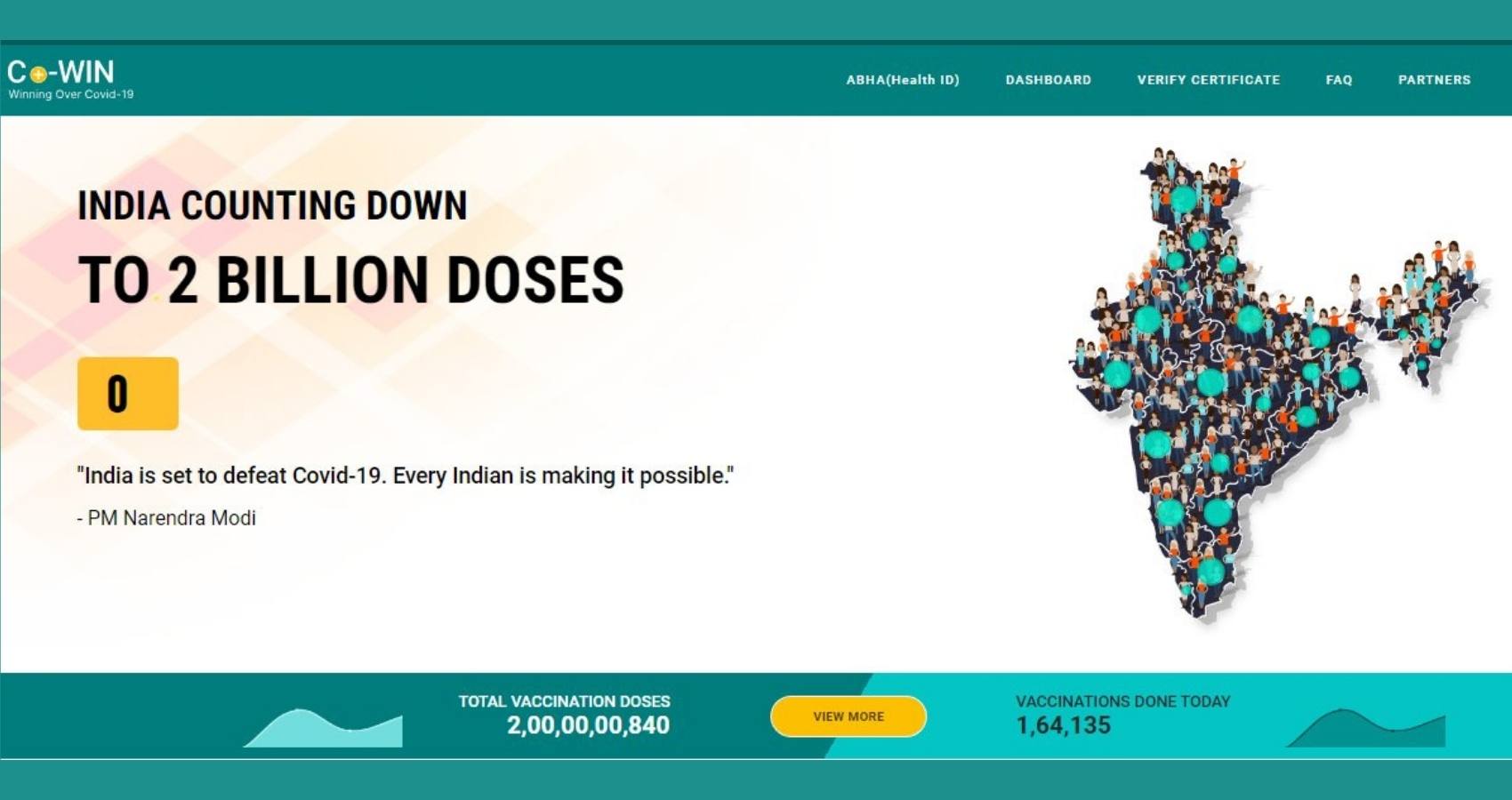

Despite his dismantling of democratic institutions, Modi remains extremely popular. He is both incredibly hardworking and politically astute, able to read the pulse of the electorate and adapt his rhetoric and tactics accordingly. Left-wing intellectuals dismiss him as a mere demagogue. They are grievously mistaken. In terms of commitment and intelligence, he is far superior to his populist counterparts such as former U.S. President Donald Trump, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, or former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Although his economic record is mixed, he has still won the trust of many poor people by supplying food and cooking gas at highly subsidized rates via schemes branded as Modi’s personal gifts to them. He has taken quickly to digital technologies, which have enabled the direct provision of welfare and the reduction of intermediary corruption. He has also presided over substantial progress in infrastructure development, with spanking new highways and airports seen as evidence of a rising India on the march under Modi’s leadership.

Nonetheless, the future of the Indian republic looks considerably less rosy than the vision promised by Modi and his acolytes. His government has not assuaged—indeed, it has actively worked to intensify—conflicts along lines of both religion and region, which will further fray the country’s social fabric. The inability or unwillingness to check environmental abuse and degradation threatens public health and economic growth. The hollowing out of democratic institutions pushes India closer and closer to becoming a democracy only in name and an electoral autocracy in practice. Far from becoming the Vishwa Guru, or “teacher to the world”—as Modi’s boosters claim—India is altogether more likely to remain what it is today: a middling power with a vibrant entrepreneurial culture and mostly fair elections alongside malfunctioning public institutions and persisting cleavages of religion, gender, caste, and region. The façade of triumph and power that Modi has erected obscures a more fundamental truth: that a principal source of India’s survival as a democratic country, and of its recent economic success, has been its political and cultural pluralism, precisely those qualities that the prime minister and his party now seek to extinguish.

PORTRAIT IN POWER

Between 2004 and 2014, India was run by Congress-led coalition governments. The prime minister was the scholarly economist Manmohan Singh. By the end of his second term, Singh was 80 and unwell, so the task of running Congress’s campaign ahead of the 2014 general elections fell to the much younger Rahul Gandhi. Gandhi is the son of Sonia Gandhi, a former president of the Congress Party, and Rajiv Gandhi, who, like his mother, Indira Gandhi, and grandfather Nehru, had served as prime minister. In a brilliant political move, Modi, who had previously been chief minister of the important state of Gujarat for a decade, presented himself as an experienced, hard-working, and entirely self-made administrator, in stark contrast to Rahul Gandhi, a dynastic scion who had never held political office and whom Modi portrayed as entitled and effete.

Sixty years of electoral democracy and three decades of market-led economic growth had made Indians increasingly distrustful of claims made on the basis of family lineage or privilege. It also helped that Modi was a more compelling orator than Rahul Gandhi and that the BJP made better use of the new media and digital technologies to reach remote corners of India. In the 2014 elections, the BJP won 282 seats, up from 116 five years earlier, while the Congress’s tally went down from 206 to a mere 44. The next general election, in 2019, again pitted Modi against Gandhi; the BJP won 303 seats to the Congress’s 52. With these emphatic victories, the BJP not only crushed and humiliated the Congress but also secured the legislative dominance of the party. In prior decades, Indian governments had typically been motley coalitions held together by compromise. The BJP’s healthy majority under Modi has given the prime minister broad latitude to act—and free rein to pursue his ambitions.

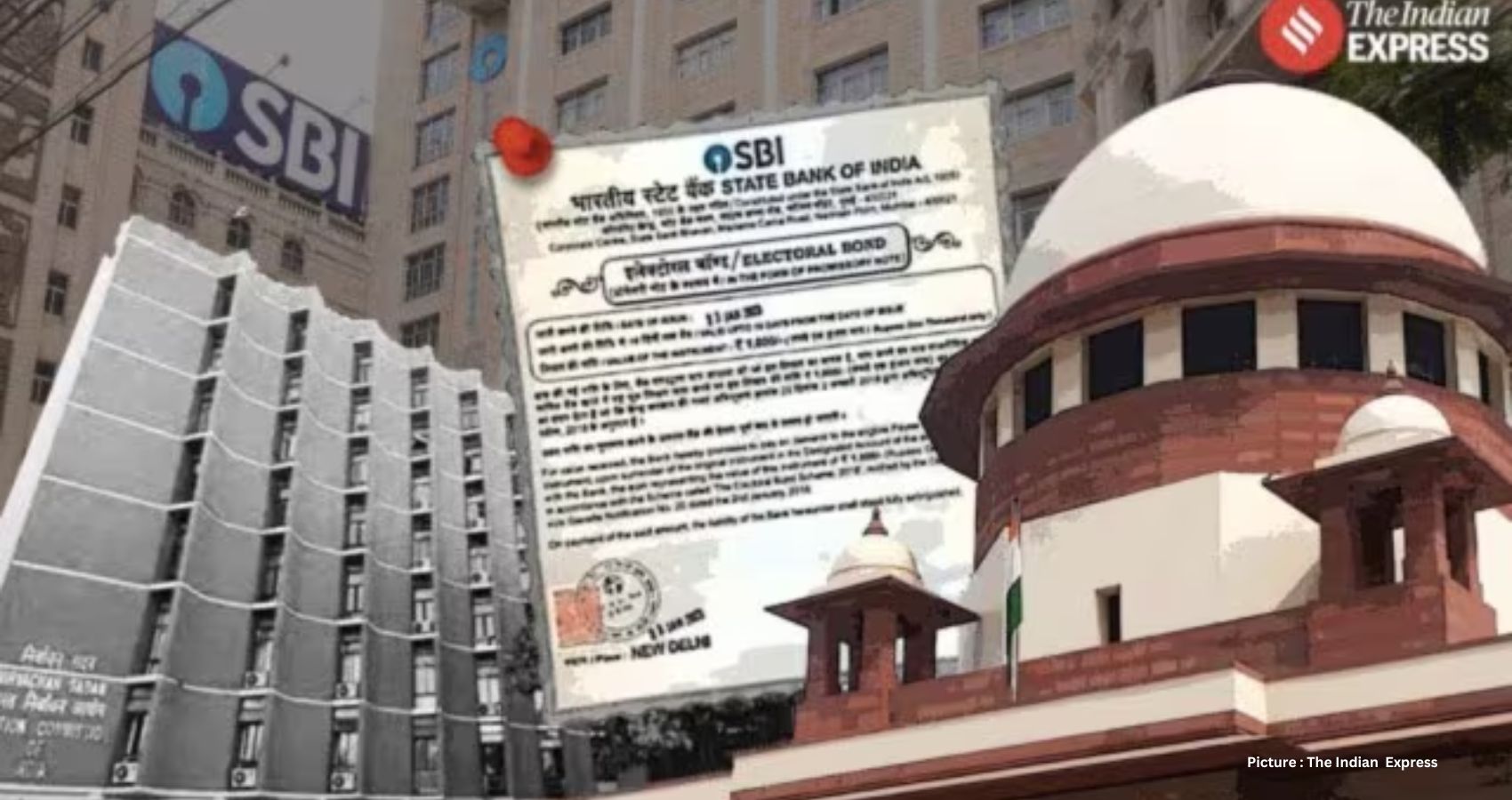

Modi presents himself as the very embodiment of the party, the government, and the nation, as almost single-handedly fulfilling the hopes and ambitions of Indians. In the past decade, his elevation has taken many forms, including the construction of the world’s largest cricket stadium, named for Modi; the portrait of Modi on the COVID-19 vaccination certificates issued by the government of India (a practice followed by no other democracy in the world); the photo of Modi on all government schemes and welfare packages; a serving judge of the Supreme Court gushing that Modi is a “visionary” and a “genius”; and Modi’s own proclamation that he had been sent by god to emancipate India’s women.

In keeping with this gargantuan cult of personality, Modi has attempted, largely successfully, to make governance and administration an instrument of his personal will rather than a collaborative effort in which many institutions and individuals work together. In the Indian system, based on the British model, the prime minister is supposed to be merely first among equals. Cabinet ministers are meant to have relative autonomy in their own spheres of authority. Under Modi, however, most ministers and ministries take instructions directly from the prime minister’s office and from officials known to be personally loyal to him. Likewise, Parliament is no longer an active theater of debate, in which the views of the opposition are taken into account in forging legislation. Many bills are passed in minutes, by voice vote, with the speakers in both houses acting in an extremely partisan manner. Opposition members of Parliament have been suspended in the dozens—and in one recent case, in the hundreds—for demanding that the prime minister and home minister make statements about such important matters as bloody ethnic conflicts in India’s borderlands and security breaches in Parliament itself.

Sadly, the Indian Supreme Court has done little to stem attacks on democratic freedoms. In past decades, the court had at least occasionally stood up for personal freedoms, and for the rights of the provinces, acting as a modest brake on the arbitrary exercise of state power. Since Modi took office, however, the Supreme Court has often given its tacit approval to the government’s misconduct, by, for example, failing to strike down punitive laws that clearly violate the Indian constitution. One such law is the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, under which it is almost impossible to get bail and which has been invoked to arrest and designate as “terrorists” hundreds of students and human rights activists for protesting peacefully on the streets against the majoritarian policies of the regime.

The civil services and the diplomatic corps are also prone to obey the prime minister and his party, even when the demands clash with constitutional norms. So does the Election Commission, which organizes elections and frames election rules to facilitate the preferences of Modi and the BJP. Thus, elections in Jammu and Kashmir and to the municipal council of Mumbai, India’s richest city, have been delayed for years largely because the ruling party remains unsure of winning them.

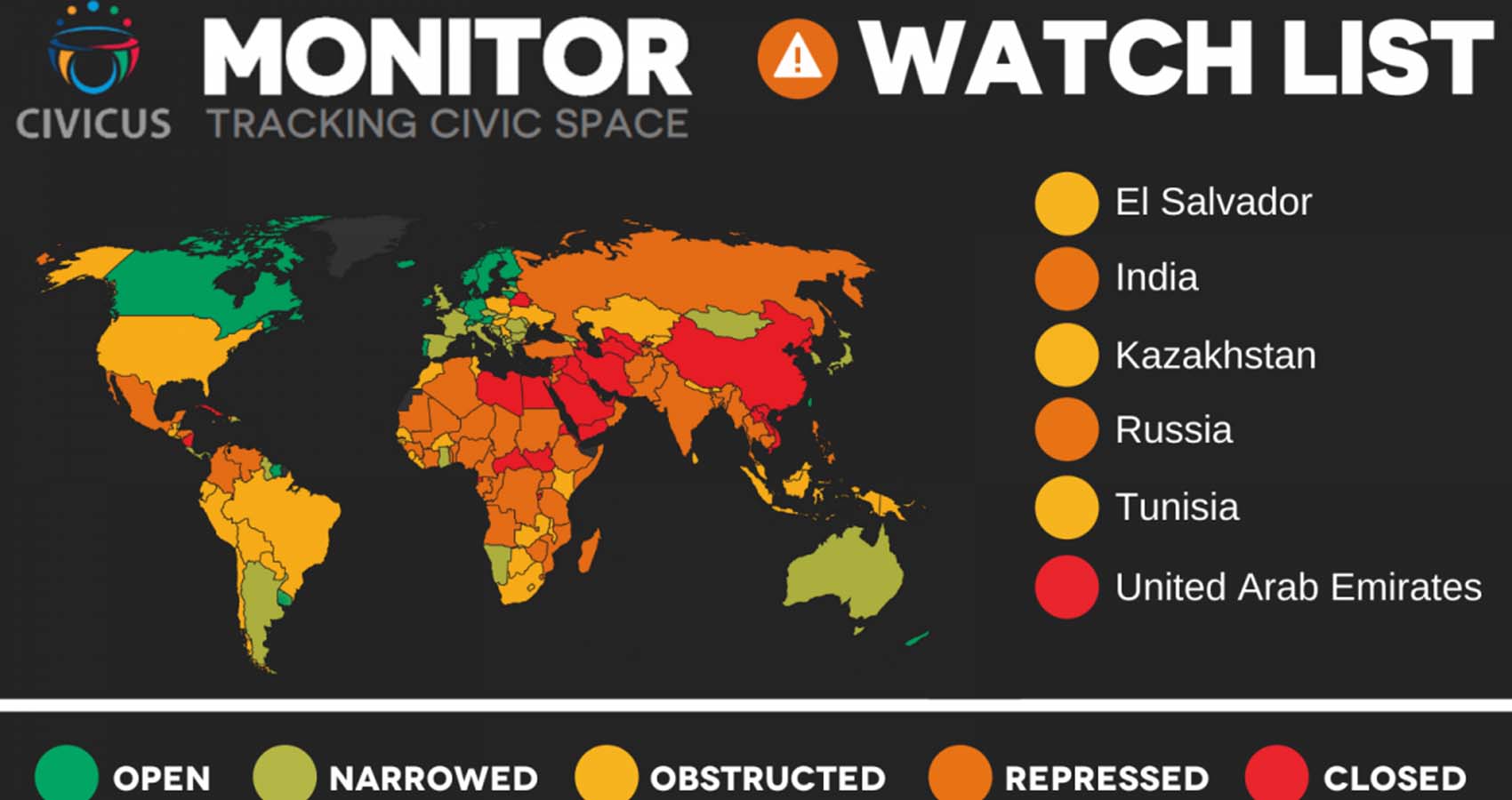

The Modi government has also worked systematically to narrow the spaces open for democratic dissent. Tax officials disproportionately target opposition politicians. Large sections of the press act as the mouthpiece of the ruling party for fear of losing government advertisements or facing vindictive tax raids. India currently ranks 161 out of 180 countries surveyed in the World Press Index, an analysis of levels of journalistic freedom. Free debate in India’s once vibrant public universities is discouraged; instead, the University Grants Commission has instructed vice chancellors to install “selfie points” on campuses to encourage students to take their photograph with an image of Modi.

This story of the systematic weakening of India’s democratic foundations is increasingly well known outside the country, with watchdog groups bemoaning the backsliding of the world’s largest democracy. But another fundamental challenge to India has garnered less attention: the erosion of the country’s federal structure. India is a union of states whose constituent units have their own governments elected on the basis of universal adult franchise. As laid down in India’s constitution, some subjects, including defense, foreign affairs, and monetary policy, are the responsibility of the government in New Delhi. Others, including agriculture, health, and law and order, are the responsibility of the states. Still others, such as forests and education, are the joint responsibility of the central government and the states. This distribution of powers allows state governments considerable latitude in designing and implementing policies for their citizens. It explains the wide variation in policy outcomes across the country—why, for example, the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have a far better record with regard to health, education, and gender equity compared with northern states such as Uttar Pradesh.

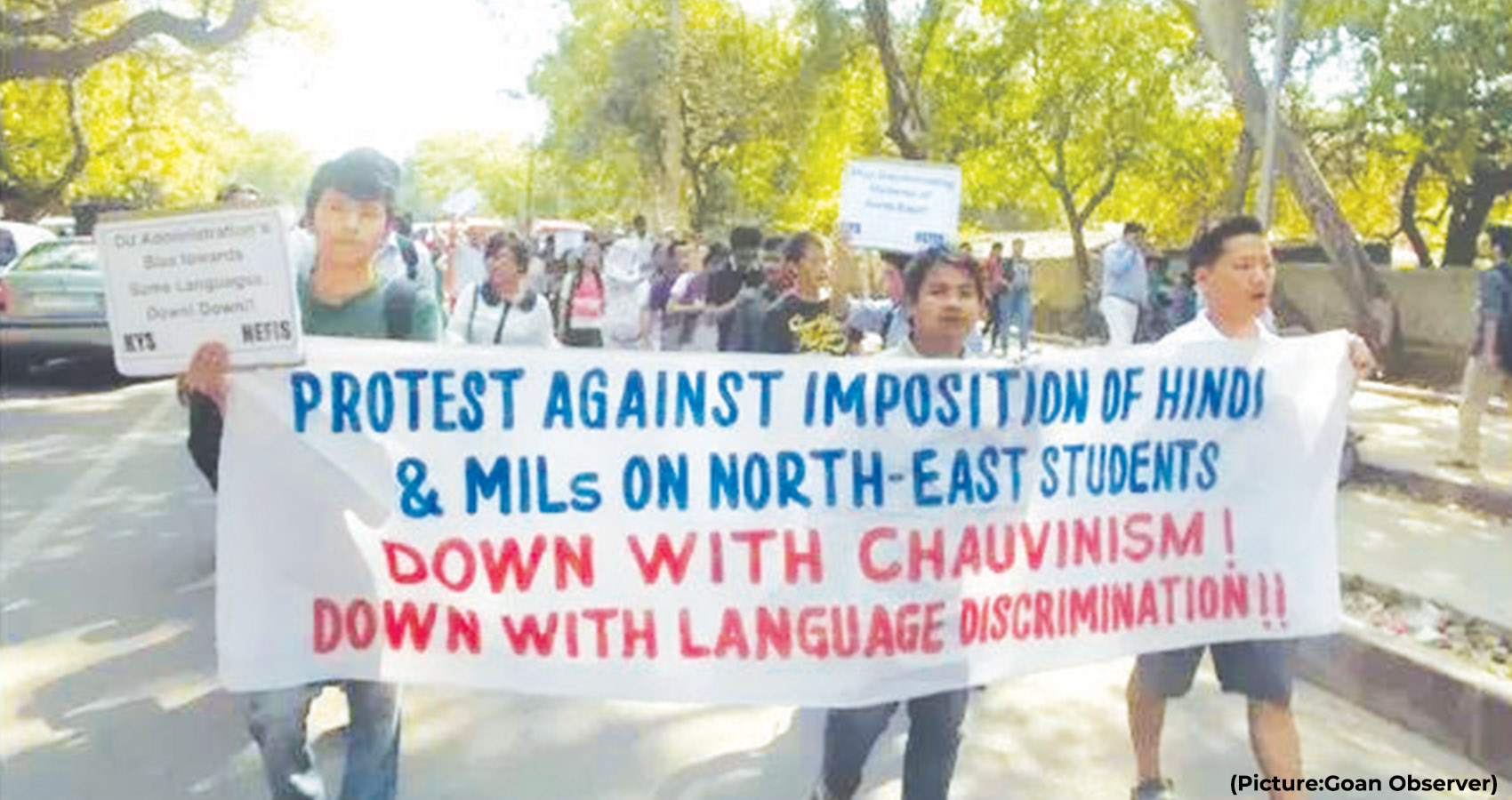

As a large, sprawling federation of states, India resembles the United States. But India’s states are more varied in terms of culture, religion, and particularly language. In that sense, India is more akin to the European Union in the continental scale of its diversity. The Bengalis, the Kannadigas, the Keralites, the Odias, the Punjabis, and the Tamils, to name just a few peoples, all have extraordinarily rich literary and cultural histories, each distinct from one another and especially from that of the heartland states of northern India where the BJP is dominant. Coalition governments respected and nourished this heterogeneity, but under Modi, the BJP has sought to compel uniformity in three ways: through imposing the main language of the north, Hindi, in states where it is scarcely spoken and where it is seen as an unwelcome competitor to the local language; through promoting the cult of Modi as the only leader of any consequence in India; and through the legal and financial powers that being in office in New Delhi bestows on it.

Since coming to power, the Modi government has assiduously undermined the autonomy of state governments run by parties other than the BJP. It has achieved this in part through the ostensibly nonpartisan office of the governor, who, in states not run by the BJP, has often acted as an agent of the ruling party in New Delhi. Laws in domains such as agriculture, nominally the realm of state governments, have been passed by the national Parliament without the consultation of the states. Since several important and populous states—including Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal—are run by popularly elected parties other than the BJP, the Modi government’s undisguised hostility toward their autonomous functioning has created a great deal of bad blood.

In this manner, in his decade in office, Modi has worked diligently to centralize and personalize political power. As chief minister of Gujarat, he gave his cabinet colleagues little to do, running the administration through bureaucrats loyal to him. He also worked persistently to tame civil society and the press in Gujarat. Since Modi became prime minister in 2014, this authoritarian approach to governance has been carried over to New Delhi. His authoritarianism has a precedent, however: the middle period of Indira Gandhi’s prime ministership, from 1971 to 1977, when she constructed a cult of personality and turned the party and government into an instrument of her will. But Modi’s subordination of institutions has gone even further. In his style of administration, he is Indira Gandhi on steroids.

A HINDU KINGDOM

For all their similarities in political style, Indira Gandhi and Modi differ markedly in terms of political ideology. Forged in the crucible of the Indian freedom struggle, inspired by the pluralistic ethos of its leader Mahatma Gandhi (who was not related to her) and of her father, Nehru, Indira Gandhi was deeply committed to the idea that India belonged equally to citizens of all faiths. For her, as for Nehru, India was not to be a Hindu version of Pakistan—a country designed to be a homeland for South Asia’s Muslims. India would not define statecraft or governance in accordance with the views of the majority religious community. India’s many minority religious groups—including Buddhists, Christians, Jains, Muslims, Parsis, and Sikhs—would all have the same status and material rights as Hindus. Modi has taken a different view. Raised as he was in the hardline milieu of the Hindu nationalist movement, he sees the cultural and civilizational character of India as defined by the demographic dominance—and long-suppressed destiny—of Hindus.

The attempt to impose Hindu hegemony on India’s present and future has two complementary elements. The first is electoral, the creation of a consolidated Hindu vote bank. Hinduism does not have the singular structure of Abrahamic religions such as Christianity or Islam. It does not elevate one religious text (such as the Bible or the Koran) or one holy city (such as Rome or Mecca) to a particularly privileged status. In Hinduism, there are many gods, many holy places, and many styles of worship. But while the ritual universe of Hinduism is pluralistic, its social system is historically highly unequal, marked by hierarchically organized status groups known as castes, whose members rarely intermarry or even break bread with one another.

The BJP under Modi has tried to overcome the pluralism of Hinduism by seeking to override caste and doctrinal differences between different groups of Hindus. It promises to construct a “Hindu Raj,” a state in which Hindus will reign supreme. Modi claims that before his ascendance, Hindus had suffered 1,200 years of slavery at the hands of Muslim rulers, such as the Mughal dynasty, and Christian rulers, such as the British—and that he will now restore Hindu pride and Hindu control over the land that is rightfully theirs. To aid this consolidation, Hindu nationalists have systematically demonized India’s large Muslim minority, painting Muslims as insufficiently apologetic for the crimes of the Muslim rulers of the past and as insufficiently loyal to the India of the present.

Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, is a belief system characterized by what I call “paranoid triumphalism.” It aims to make Hindus fearful so as to compel them to act together and ultimately dominate those Indians who are not Hindus. At election time, the BJP hopes to make Hindus vote as Hindus. Since Hindus constitute roughly 80 percent of the population, if 60 percent of them vote principally on the basis of their religious affiliation in India’s multiparty, first-past-the-post system, that amounts to 48 percent of the popular vote for the BJP—enough to get Modi and his party elected by a comfortable margin. Indeed, in the 2019 elections, the BJP won 56 percent of seats with 37 percent of the popular vote. So complete is the ruling party’s disregard for the political rights of India’s 200 million or so Muslims that, except when compelled to do so in the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir, it rarely picks Muslim candidates to compete in elections. And yet it can still comfortably win national contests. The BJP has 397 members in the two houses of the Indian parliament. Not one is a Muslim.

Electoral victory has enabled the second element of Hindutva—the provision of an explicitly Hindu veneer to the character of the Indian state. Modi himself chose to contest the parliamentary elections from Varanasi, an ancient city with countless temples that is generally recognized as the most important center of Hindu identity. He has presented himself as a custodian of Hindu traditions, claiming that in his youth, he wandered and meditated in the forests of the Himalaya in the manner of the sages of the past. He has, for the first time, made Hindu rituals central to important secular occasions, such as the inauguration of a new Parliament building, which was conducted by him alone, flanked by a phalanx of chanting priests, but with the members of Parliament, the representatives of the people, conspicuously absent. He also presided, in similar fashion, over religious rituals in Varanasi, with the priests chanting, “Glory to the king.” In January, Modi was once again the star of the show as he opened a large temple in the city of Ayodhya on a site claimed to be the birthplace of the god Rama. Whenever television channels obediently broadcast such proceedings live across India, their cameras focus on the elegantly attired figure of Modi. The self-proclaimed Hindu monk of the past has thus become, in symbol if not in substance, the Hindu emperor of the present.

THE BURDENS OF THE FUTURE

The emperor benefits from having few plausible rivals. Modi’s enduring political success is in part enabled by a fractured and nepotistic opposition. In a belated bid to stall the BJP from winning a third term, as many as 28 parties have come together to fight the forthcoming general elections under a common umbrella. They have adopted the name the Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance, an unwieldy moniker that can be condensed to the crisp acronym INDIA.

Some parties in this alliance are very strong in their own states. Others have a base among particular castes. But the only party in the alliance with pretensions to being a national party is the Congress. Despite his dismal political record, Rahul Gandhi remains the principal leader of the Congress. In public appearances, he is often flanked by his sister, who is the party’s general-secretary, or his mother, reinforcing his sense of entitlement. The major regional parties, with influence in states such as Bihar, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, are also family firms, with leadership often passing from father to son. Although their local roots make them competitive in state elections, when it comes to a general election, the dynastic baggage they carry puts them at a distinct disadvantage against a party led by a self-made man such as Modi, who can present himself as devoted entirely and utterly to the welfare of his fellow citizens rather than as the bearer of family privilege. INDIA will struggle to unseat Modi and the BJP and may hope, at best, to dent their commanding majority in Parliament.

The prime minister also faces little external pressure. In other contexts, one might expect a certain amount of critical scrutiny of Modi’s authoritarian ways from the leaders of Western democracies. But this has not happened, partly because of the ascendance of the Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Xi has mounted an aggressive challenge to Western hegemony and positioned China as a superpower deserving equal respect and an equal say in world affairs as the United States—moves that have worked entirely to Modi’s advantage. The Indian prime minister has played the U.S. establishment brilliantly, using the large and wealthy Indian diaspora to make his (and India’s) importance visible to the White House.

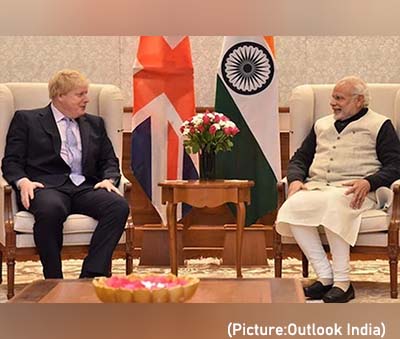

In April 2023, India officially overtook China as the most populous country in the world. It has the fifth-largest economy. It has a large and reasonably well-equipped military. All these factors make it ever more appealing to the United States as a counterweight to China. Both the Trump and the Biden administrations have shown an extraordinary indulgence toward Modi, continuing to hail him as the leader of the “world’s largest democracy” even as that appellation becomes less credible under his rule. The attacks on minorities, the suppression of the press, and the arrest of civil rights activists have attracted scarcely a murmur of disapproval from the State Department or the White House. The recent allegations that the Indian government tried to assassinate a U.S. citizen of Sikh descent are likely to fade without any action or strong public criticism. Meanwhile, the leaders of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, seeking a greater share of the Indian market (not least in sales of sophisticated weaponry), have all been unctuous in their flattery of Modi.

The rampant environmental degradation across the country further threatens the sustainability of economic growth. Even in the absence of climate change, India would be an environmental disaster zone. Its cities have the highest rates of air pollution in the world. Many of its rivers are ecologically dead, killed by untreated industrial effluents and domestic sewage. Its underground aquifers are depleting rapidly. Much of its soil is contaminated with chemicals. Its forests are despoiled and in the process of becoming much less biodiverse, thanks to invasive nonnative weeds.

This degradation has been enabled by an antiquated economic ideology that adheres to the mistaken belief that only rich countries need to behave responsibly toward nature. India, it is said, is too poor to be green. In fact, countries such as India, with their higher population densities and more fragile tropical ecologies, need to care as much, or more, about how to use natural resources wisely. But regimes led by both the Congress and the BJP have granted a free license to coal and petroleum extraction and other polluting industries. No government has so actively promoted destructive practices as Modi’s. It has eased environmental clearances for polluting industries and watered down various regulations. The environmental scholar Rohan D’ Souza has written that by 2018, “the slash and burn attitude of gutting and weakening existing environmental institutions, laws, and norms was extended to forests, coasts, wildlife, air, and even waste management.” When Modi came to power in 2014, India ranked 155 out of 178 countries assessed by the Environmental Performance Index, which estimates the sustainability of a country’s development in terms of the state of its air, water, soils, natural habitats, and so on. By 2022, India ranked last, 180 out of 180.

The effects of these varied forms of environmental deterioration exact a horrific economic and social cost on hundreds of millions of people. Degradation of pastures and forests imperils the livelihoods of farmers. Unregulated mining for coal and bauxite displaces entire rural communities, making their people ecological refugees. Air pollution in cities endangers the health of children, who miss school, and of workers, whose productivity declines. Unchecked, these forms of environmental abuse will impose ever-greater burdens on Indians yet unborn.

These future generations of Indians will also have to bear the costs of the dismantling of democratic institutions overseen by Modi and his party. A free press, independent regulatory institutions, and an impartial and fearless judiciary are vital for political freedoms, for acting as a check on the abuse of state power, and for nurturing an atmosphere of trust among citizens. To create, or perhaps more accurately, re-create, them after Modi and the BJP finally relinquish power will be an arduous task.

The strains placed on Indian federalism may boil over in 2026, when parliamentary seats are scheduled to be reallocated according to the next census, to be conducted in that year. Then, what is now merely a divergence between north and south might become an actual divide. In 2001, when a reallocation of seats based on population was proposed, the southern states argued that it would discriminate against them for following progressive health and education policies in prior decades that had reduced birth rates and enhanced women’s freedom. The BJP-led coalition government then in power recognized the merits of the south’s case and, with the consent of the opposition, proposed that the reallocation be delayed for a further 25 years.

In 2026, the matter will be reopened. One proposed solution is to emulate the U.S. model, in which congressional districts reflect population size while each state has two seats in the Senate, irrespective of population. Perhaps having the Rajya Sabha, or upper house, of the Indian Parliament restructured on similar principles may help restore faith in federalism. But if Modi and the BJP are in power, they will almost certainly mandate the process of reallocation based on population in both the Lok Sabha, the lower house, and the Rajya Sabha, which will then substantially favor the more populous if economically lagging states of the north. The southern states are bound to protest. Indian federalism and unity will struggle to cope with the fallout.

If the BJP achieves a third successive electoral victory in May, the creeping majoritarianism under Modi could turn into galloping majoritarianism, a trend that poses a fundamental challenge to Indian nationhood. Democratic- and pluralistic-minded Indians warn of the dangers of India becoming a country like Pakistan, defined by religious identity. A more salient cautionary tale might be Sri Lanka’s. With its educated population, good health care, relatively high position of women (compared with India and all other countries in South Asia), its capable and numerous professional class, and its attractiveness as a tourist destination, Sri Lanka was poised in the 1970s to join Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan as one of the so-called Asian Tigers. But then, a deadly mix of religious and linguistic majoritarianism reared its head. The Sinhala-speaking Buddhist majority chose to consolidate itself against the Tamil-speaking minority, who were themselves largely Hindus. Through the imposition of Sinhalese as the official language and Buddhism as the official religion, a deep division was created, provoking protests by the Tamils, peaceful at first but increasingly violent when crushed by the state. Three decades of bloody civil war ensued. The conflict formally ended in 2009, but the country has not remotely recovered, in social, economic, political, or psychological terms.

India will probably not go the way of

Sri Lanka. A full-fledged civil war between Hindus and Muslims, or between north and south, is unlikely. But the Modi government is jeopardizing a key source of Indian strength: its varied forms of pluralism. One might usefully contrast Modi’s time in office with the years between 1989 and 2014, when neither the Congress nor the BJP had a majority in Parliament. In that period, prime ministers had to bring other parties into government, allocating important ministries to its leaders. This fostered a more inclusive and collaborative style of governance, more suitable to the size and diversity of the country itself. States run by parties other than the BJP or the Congress found representation at the center, their voices heard and their concerns taken into account. Federalism flourished, and so did the press and the courts, which had more room to follow an independent path. It may be no coincidence that it was in this period of coalition government that India experienced three decades of steady economic growth.

When India became free from British rule in 1947, many skeptics thought it was too large and too diverse to survive as a single nation and its population too poor and illiterate to be trusted with a democratic system of governance. Many predicted that the country would Balkanize, become a military dictatorship, or experience mass famine. That those dire scenarios did not come to pass was largely because of the sagacity of India’s founding figures, who nurtured a pluralist ethos that respected the rights of religious and linguistic minorities and who sought to balance the rights of the individual and the state, as well as those of the central government and the provinces. This delicate calculus enabled the country to stay united and democratic and allowed its people to steadily overcome the historic burdens of poverty and discrimination.

The last decade has witnessed the systematic erosion of those varied forms of pluralism. One party, the BJP, and within it, one man, the prime minister, are judged to represent India to itself and to the world. Modi’s charisma and popular appeal have consolidated this dominance, electorally speaking. Yet the costs are mounting. Hindus impose themselves on Muslims, the central government imposes itself on the provinces, the state further curtails the rights and freedoms of citizens. Meanwhile, the unthinking imitation of Western models of energy-intensive and capital-intensive industrialization is causing profound and, in many cases, irreversible environmental damage.

Modi and the BJP seem poised to win their third general election in a row. This victory would further magnify the prime minister’s aura, enhancing his image as India’s redeemer. His supporters will boast that their man is assuredly taking his country toward becoming the Vishwa Guru, the teacher to the world. Yet such triumphalism cannot mask the deep fault lines underneath, which—unless recognized and addressed—will only widen in the years to come.

India, a country with 1.4 billion people and the largest democracy in the world, has a constitutional framework of India is parliamentary, which is led by the elected representative and overseen by the first person of the country, the President of India.

India, a country with 1.4 billion people and the largest democracy in the world, has a constitutional framework of India is parliamentary, which is led by the elected representative and overseen by the first person of the country, the President of India. Murmu said that she started her journey of life from a small tribal village in Odisha in the eastern part of the country. From the background that she came from, it was like a dream for her to get elementary education, she said. Her election to the top constitutional post proves that in India, the poor can not only dream but also fulfill those aspirations, she added.

Murmu said that she started her journey of life from a small tribal village in Odisha in the eastern part of the country. From the background that she came from, it was like a dream for her to get elementary education, she said. Her election to the top constitutional post proves that in India, the poor can not only dream but also fulfill those aspirations, she added.

He had posted an image from the 1983-movie Kissi Se Na Kehna, showing a hotel’s name changing from Honeymoon Hotel to Hanuman Hotel. He wrote: “Before 2014: Honeymoon Hotel. After 2014: Hanuman Hotel.”

He had posted an image from the 1983-movie Kissi Se Na Kehna, showing a hotel’s name changing from Honeymoon Hotel to Hanuman Hotel. He wrote: “Before 2014: Honeymoon Hotel. After 2014: Hanuman Hotel.”

As per media reports, over 99 per cent of the total 4,796 electors cast their votes in the presidential poll held at the Parliament House and the state legislative assemblies. As many as 10 states and the Union Territory of Puducherry recorded a 100 per cent turnout.

As per media reports, over 99 per cent of the total 4,796 electors cast their votes in the presidential poll held at the Parliament House and the state legislative assemblies. As many as 10 states and the Union Territory of Puducherry recorded a 100 per cent turnout. BSP leader Atul Singh who is in jail could not vote. Shiv Sena leaders, Gajanan Kirtikar and Hemant Godse, also did not vote. AIMIM leader Imtiyaz Jaleel also was among the eight who did not vote. Senior leaders like Union Minister Nirmala Sitharaman came in a PPE, while former PM Manmohan Singh and SP patriarch Mulayam Singh Yadav came in wheelchairs to cast their votes.

BSP leader Atul Singh who is in jail could not vote. Shiv Sena leaders, Gajanan Kirtikar and Hemant Godse, also did not vote. AIMIM leader Imtiyaz Jaleel also was among the eight who did not vote. Senior leaders like Union Minister Nirmala Sitharaman came in a PPE, while former PM Manmohan Singh and SP patriarch Mulayam Singh Yadav came in wheelchairs to cast their votes.

India celebrated its dedication commitment to prevent Covid virus as it has now provided over two billion Billion Vaccines to its 1.4 billion people. Celebrations were across the nation, after India administered 2 billion doses of vaccinations against COVID-19.

India celebrated its dedication commitment to prevent Covid virus as it has now provided over two billion Billion Vaccines to its 1.4 billion people. Celebrations were across the nation, after India administered 2 billion doses of vaccinations against COVID-19.

The report says about China that by 2030 there will be an urban population of 1.05 billion. Whereas the population of people living in cities in Asia will be 2.99 billion. In South Asia this number will be 98.76 million.

The report says about China that by 2030 there will be an urban population of 1.05 billion. Whereas the population of people living in cities in Asia will be 2.99 billion. In South Asia this number will be 98.76 million.

Senator Markey said the United States “must encourage the Indian government to fulfill its commitment to its own citizens the right of all individuals to practice and propagate religious [beliefs] enshrined in India’s constitution.” Senator Markey said it was “incumbent on the Indian government to uphold the principles of pluralism and secularism which are embedded in the Indian constitution.”

Senator Markey said the United States “must encourage the Indian government to fulfill its commitment to its own citizens the right of all individuals to practice and propagate religious [beliefs] enshrined in India’s constitution.” Senator Markey said it was “incumbent on the Indian government to uphold the principles of pluralism and secularism which are embedded in the Indian constitution.”

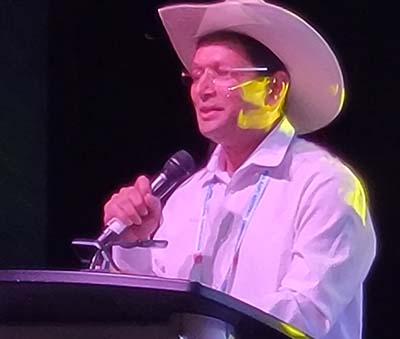

There was a sense of joy and relief on the faces of the over 1,000 physicians who have come together to celebrate their achievements, contributions, and to network and deepen their relationship even as the Covid Pandemic is waning and people are able to mingle freely and interact with one another cautiously.

There was a sense of joy and relief on the faces of the over 1,000 physicians who have come together to celebrate their achievements, contributions, and to network and deepen their relationship even as the Covid Pandemic is waning and people are able to mingle freely and interact with one another cautiously. “Our physician members have worked very hard during the covid 19 pandemic. The 2022 convention is a perfect time to heal the healers with a special focus on wellness,” said Dr. Jayesh Shah, Chair of AAPI Convention 2022. Dr. Shah praised the dedication and generosity of each member for giving their best, to make this Convention truly a memorable one for every participant.

“Our physician members have worked very hard during the covid 19 pandemic. The 2022 convention is a perfect time to heal the healers with a special focus on wellness,” said Dr. Jayesh Shah, Chair of AAPI Convention 2022. Dr. Shah praised the dedication and generosity of each member for giving their best, to make this Convention truly a memorable one for every participant. Honoring India and its 75 years of Independence Day celebrations- co-sponsored by the Embassy of India & the Consulate General of India (CGI) – Houston, AAPI delegates had a rare glimpse to the rich cultural heritage of India through a video presentation depicting the unique diversity of India and a variety mesmerizing performance of Indian/Mexican Fusion Dances, ranging from Bharatnatyam, folk dances, and the traditional Indian dances in sync with Mexican pop dances, which were a treat to the hearts and souls of everyone. National Spieling Bee Champion 2022 Harini Logan was recognized during the convention Gala.

Honoring India and its 75 years of Independence Day celebrations- co-sponsored by the Embassy of India & the Consulate General of India (CGI) – Houston, AAPI delegates had a rare glimpse to the rich cultural heritage of India through a video presentation depicting the unique diversity of India and a variety mesmerizing performance of Indian/Mexican Fusion Dances, ranging from Bharatnatyam, folk dances, and the traditional Indian dances in sync with Mexican pop dances, which were a treat to the hearts and souls of everyone. National Spieling Bee Champion 2022 Harini Logan was recognized during the convention Gala. The convention is focused on themes such as how to take care of self and find satisfaction and happiness in the challenging situations they are in, while serving hundreds of patients everyday of their dedicated and noble profession.

The convention is focused on themes such as how to take care of self and find satisfaction and happiness in the challenging situations they are in, while serving hundreds of patients everyday of their dedicated and noble profession. Some of the major events at the convention include: Workshops and hands-on sessions on well-being, 10-12 hours of CMEs, Women’s Forum, CEOs Forum, AAPI Got Talent, Mehfil, Bollywood Nite, Fashion Show, Medical Jeopardy, Poster/Research Contest, Alumni and Young Physicians events and Exhibition and Sale of Jewelry, Clothing, Medical Equipment, Pharma, Finance and many more.

Some of the major events at the convention include: Workshops and hands-on sessions on well-being, 10-12 hours of CMEs, Women’s Forum, CEOs Forum, AAPI Got Talent, Mehfil, Bollywood Nite, Fashion Show, Medical Jeopardy, Poster/Research Contest, Alumni and Young Physicians events and Exhibition and Sale of Jewelry, Clothing, Medical Equipment, Pharma, Finance and many more. “Welcome to my home city, San Antonio and thank you for coming here to the annual convention offering extensive academic presentations, recognition of achievements and achievers, and professional networking at the alumni and evening social events,” Dr. Gotimukula added. For more details, please visit:

“Welcome to my home city, San Antonio and thank you for coming here to the annual convention offering extensive academic presentations, recognition of achievements and achievers, and professional networking at the alumni and evening social events,” Dr. Gotimukula added. For more details, please visit:

So the role is more akin to that of the British monarch or monarchs in countries like the Netherlands or Spain: a referee over a parliamentary system where ministers possess the real power. Countries like Germany and Israel have presidencies similar to India’s.

So the role is more akin to that of the British monarch or monarchs in countries like the Netherlands or Spain: a referee over a parliamentary system where ministers possess the real power. Countries like Germany and Israel have presidencies similar to India’s.

When one of my cousins in Mumbai attended a Catholic school in the 1970s and 1980s, his circle of friends included people of numerous religions — Hindus, Muslims and Parsis, among others. They would go to each other’s homes and to each other’s houses of worship — even to pray, if there was an exam coming up!

When one of my cousins in Mumbai attended a Catholic school in the 1970s and 1980s, his circle of friends included people of numerous religions — Hindus, Muslims and Parsis, among others. They would go to each other’s homes and to each other’s houses of worship — even to pray, if there was an exam coming up! In short, if you’re someone in the Hindu diaspora who has economic or social power and you don’t speak up against state-sanctioned violence and discrimination in India, you might as well be participating in it. If you’re against discrimination here, then you’ve got to be against discrimination there.

In short, if you’re someone in the Hindu diaspora who has economic or social power and you don’t speak up against state-sanctioned violence and discrimination in India, you might as well be participating in it. If you’re against discrimination here, then you’ve got to be against discrimination there.

Modi’s party took no action against the two BJP leaders until Sunday, when a sudden chorus of diplomatic outrage began with Qatar and Kuwait summoning their Indian ambassadors to protest. The BJP suspended Sharma and expelled Jindal and issued a rare statement saying it “strongly denounces insult of any religious personalities,” a move that was welcomed by Qatar and Kuwait.

Modi’s party took no action against the two BJP leaders until Sunday, when a sudden chorus of diplomatic outrage began with Qatar and Kuwait summoning their Indian ambassadors to protest. The BJP suspended Sharma and expelled Jindal and issued a rare statement saying it “strongly denounces insult of any religious personalities,” a move that was welcomed by Qatar and Kuwait.

“We have noted the release of the US State Department 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom, and ill-informed comments by senior US officials. It is unfortunate that vote bank politics is being practiced in international relations. We would urge that assessments based on motivated inputs and biased views be avoided,” said foreign ministry spokesperson Arindam Bagchi.

“We have noted the release of the US State Department 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom, and ill-informed comments by senior US officials. It is unfortunate that vote bank politics is being practiced in international relations. We would urge that assessments based on motivated inputs and biased views be avoided,” said foreign ministry spokesperson Arindam Bagchi.

The prospect of upsetting Washington should be particularly concerning for Indian policymakers. The United States has become one of New Delhi’s most important partners, particularly as India tries to stand up to Chinese aggression in the Himalayas. But although Washington is not happy that New Delhi has refused to condemn Russian aggression, Indian policymakers have calculated that their country is so central to U.S. efforts to counterbalance China that India will remain immune to a potential backlash. So far, they’ve been right; the United States has issued only muted criticisms of Indian neutrality. Yet Washington’s patience is not endless, and the longer Russia prosecutes its war without India changing its position, the more likely the United States will be to view India as an unreliable partner. It may not want to, but ultimately New Delhi will have to pick between Russia and the West.

The prospect of upsetting Washington should be particularly concerning for Indian policymakers. The United States has become one of New Delhi’s most important partners, particularly as India tries to stand up to Chinese aggression in the Himalayas. But although Washington is not happy that New Delhi has refused to condemn Russian aggression, Indian policymakers have calculated that their country is so central to U.S. efforts to counterbalance China that India will remain immune to a potential backlash. So far, they’ve been right; the United States has issued only muted criticisms of Indian neutrality. Yet Washington’s patience is not endless, and the longer Russia prosecutes its war without India changing its position, the more likely the United States will be to view India as an unreliable partner. It may not want to, but ultimately New Delhi will have to pick between Russia and the West.

“The idea to bombard the courts with so many petitions is to keep the Muslims in check and the communal pot simmering,” said Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a political analyst and commentator. “It is a way to tell Muslims that their public display of faith in India is no more accepted and that the alleged humiliation heaped on them by Muslim rulers of the medieval past should be redressed now.”

“The idea to bombard the courts with so many petitions is to keep the Muslims in check and the communal pot simmering,” said Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a political analyst and commentator. “It is a way to tell Muslims that their public display of faith in India is no more accepted and that the alleged humiliation heaped on them by Muslim rulers of the medieval past should be redressed now.”

The Catholic Union has, with other Christian groups, already challenged in the Supreme Court the terrible laws that deny Dalit Christians the protection of Constitutional provisions as given to their counterparts professing Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist religions as well as those not practicing any religion at all.

The Catholic Union has, with other Christian groups, already challenged in the Supreme Court the terrible laws that deny Dalit Christians the protection of Constitutional provisions as given to their counterparts professing Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist religions as well as those not practicing any religion at all.

The gaps: 8% of all deaths in India are never registered, according to government data with just 20% of deaths being medically certified. In certain states like Bihar, Nagaland and Manipur, the registration of deaths with the civil registration system (CRS) is less than 50%. In fact, just one state — Goa — has a 100% record in registering all its deaths with the CRS. The Centre and the states, while dismissing WHO’s report, cited the death registration figures from the CRS to buttress their claims that India’s official Covid-19 fatality count is up to date.

The gaps: 8% of all deaths in India are never registered, according to government data with just 20% of deaths being medically certified. In certain states like Bihar, Nagaland and Manipur, the registration of deaths with the civil registration system (CRS) is less than 50%. In fact, just one state — Goa — has a 100% record in registering all its deaths with the CRS. The Centre and the states, while dismissing WHO’s report, cited the death registration figures from the CRS to buttress their claims that India’s official Covid-19 fatality count is up to date.

Though the Indian side stated that it would demonstrate the same speed and urgency that it did in concluding recent FTAs with the UAE and Australia in recent months, yet nothing can’t be said for sure about an Indo-UK FTA, as there are many thorny issues on both sides.

Though the Indian side stated that it would demonstrate the same speed and urgency that it did in concluding recent FTAs with the UAE and Australia in recent months, yet nothing can’t be said for sure about an Indo-UK FTA, as there are many thorny issues on both sides.

In 2021, the report said in its key findings, “The Indian government escalated its promotion and enforcement of policies — including those promoting a Hindu-nationalist agenda — that negatively affected Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Dalits, and other religious minorities. The government continued to systemize its ideological vision of a Hindu state at both the national and state levels through the use of both existing and new laws and structural changes hostile to the country’s religious minorities”.

In 2021, the report said in its key findings, “The Indian government escalated its promotion and enforcement of policies — including those promoting a Hindu-nationalist agenda — that negatively affected Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Dalits, and other religious minorities. The government continued to systemize its ideological vision of a Hindu state at both the national and state levels through the use of both existing and new laws and structural changes hostile to the country’s religious minorities”.

Professor Rohit Chopra, academic and author, drew attention to the infiltration of the Hindu supremacist ideology in all levels of the government, legacy media, and social media.

Professor Rohit Chopra, academic and author, drew attention to the infiltration of the Hindu supremacist ideology in all levels of the government, legacy media, and social media.

Dr. Shivangi is of the opinion that “It is apt time India should think alternative suppliers source. What can be a better source than US? We have a great opportunity here as our Senior Senator from Mississippi has been elected as a Ranking member of the US Armed Service Committee of the US Senate. With his assistance and good offices, especially after 2+2 summit, I hope and look forward to such increased collaboration with the successful Indo pacific QUAD treaty.

Dr. Shivangi is of the opinion that “It is apt time India should think alternative suppliers source. What can be a better source than US? We have a great opportunity here as our Senior Senator from Mississippi has been elected as a Ranking member of the US Armed Service Committee of the US Senate. With his assistance and good offices, especially after 2+2 summit, I hope and look forward to such increased collaboration with the successful Indo pacific QUAD treaty.

This reporter had asked if India was concerned over the growing diplomatic, military and economic ties between China and Russia. And in light of that concern, is India going to reduce its reliance on Russia economically and militarily?

This reporter had asked if India was concerned over the growing diplomatic, military and economic ties between China and Russia. And in light of that concern, is India going to reduce its reliance on Russia economically and militarily?

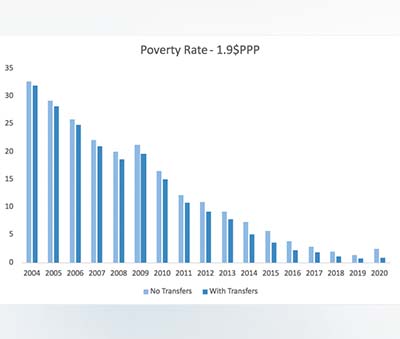

Source: NSS 2011-12 MMRP data; Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE) growth rates for estimates of monthly per capita consumption; authors’ calculations.

Source: NSS 2011-12 MMRP data; Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE) growth rates for estimates of monthly per capita consumption; authors’ calculations. Our paper presents a consistent time series of poverty and (real) inequality in India for each of the years 2004-2020. Our estimate of real inequality (Figure 3) shows that consumption inequality has also declined, and in 2020 is very close to the lowest historical level of 0.28. Poverty and inequality trends can be emotive, controversial, and confusing. Consumption inequality is lower than income inequality, which itself is lower than wealth inequality. And each can show different trends. The levels and trends are different, and intermingled use should carry a warning about this when discussing “inequality.”

Our paper presents a consistent time series of poverty and (real) inequality in India for each of the years 2004-2020. Our estimate of real inequality (Figure 3) shows that consumption inequality has also declined, and in 2020 is very close to the lowest historical level of 0.28. Poverty and inequality trends can be emotive, controversial, and confusing. Consumption inequality is lower than income inequality, which itself is lower than wealth inequality. And each can show different trends. The levels and trends are different, and intermingled use should carry a warning about this when discussing “inequality.”

Near the end of the trip, Thurman met with Mahatma Gandhi. They talked, the books record, for about three hours, covering a wide range of issues: segregation, faith, nonviolent resistance. The conversation and the trip made a lasting impression on Thurman. So when he came back to Howard, he developed his interpretation of nonviolence – not as a political tactic, but as a spiritual lifestyle. He shared his views with sermons, speeches, and eventually what came to be an incredibly influential book, Jesus and the Disinherited.

Near the end of the trip, Thurman met with Mahatma Gandhi. They talked, the books record, for about three hours, covering a wide range of issues: segregation, faith, nonviolent resistance. The conversation and the trip made a lasting impression on Thurman. So when he came back to Howard, he developed his interpretation of nonviolence – not as a political tactic, but as a spiritual lifestyle. He shared his views with sermons, speeches, and eventually what came to be an incredibly influential book, Jesus and the Disinherited.

“What does Modi need to do to India’s Muslim population before we will stop considering them a partner in peace?” Omar, who belongs to President Joe Biden’s Democratic Party, said last week.

“What does Modi need to do to India’s Muslim population before we will stop considering them a partner in peace?” Omar, who belongs to President Joe Biden’s Democratic Party, said last week.

Evidently, the negation – talking about the opponent’s past and not their own present – is the core of the mobilization technique of the BJP and its supporters, which shifts the onus of evaluation from the present to the past.

Evidently, the negation – talking about the opponent’s past and not their own present – is the core of the mobilization technique of the BJP and its supporters, which shifts the onus of evaluation from the present to the past.

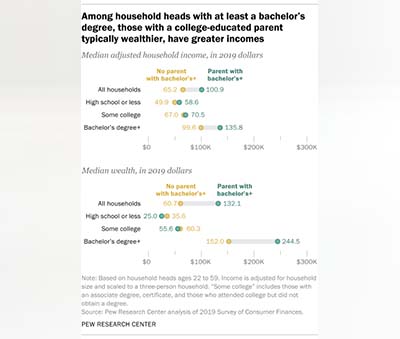

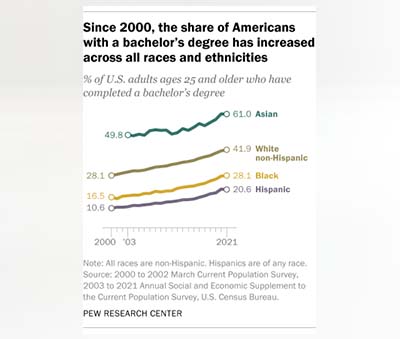

There are racial and ethnic differences in college graduation patterns, as well as in the reasons for not completing a degree. Among adults ages 25 and older, 61% of Asian Americans have a bachelor’s degree or more education, along with 42% of White adults, 28% of Black adults and 21% of Hispanic adults, according to 2021

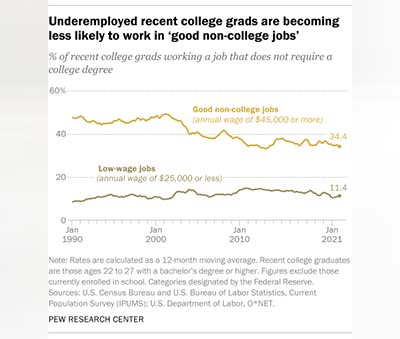

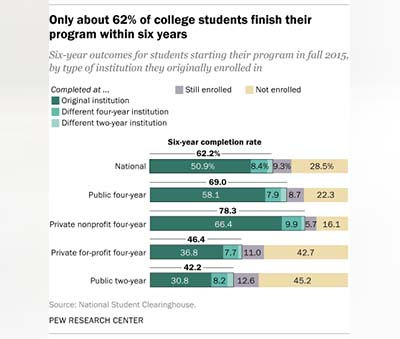

There are racial and ethnic differences in college graduation patterns, as well as in the reasons for not completing a degree. Among adults ages 25 and older, 61% of Asian Americans have a bachelor’s degree or more education, along with 42% of White adults, 28% of Black adults and 21% of Hispanic adults, according to 2021  Only 62% of students who start a degree or certificate program finish their program within six years, according to the most recent data from the

Only 62% of students who start a degree or certificate program finish their program within six years, according to the most recent data from the  The unemployment rate is lower for college graduates than for workers without a bachelor’s degree, and that gap widened as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. In February 2020, just before the

The unemployment rate is lower for college graduates than for workers without a bachelor’s degree, and that gap widened as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. In February 2020, just before the  When it comes to income and wealth accumulation, first-generation college graduates lag substantially behind those with college-educated parents, according to a

When it comes to income and wealth accumulation, first-generation college graduates lag substantially behind those with college-educated parents, according to a

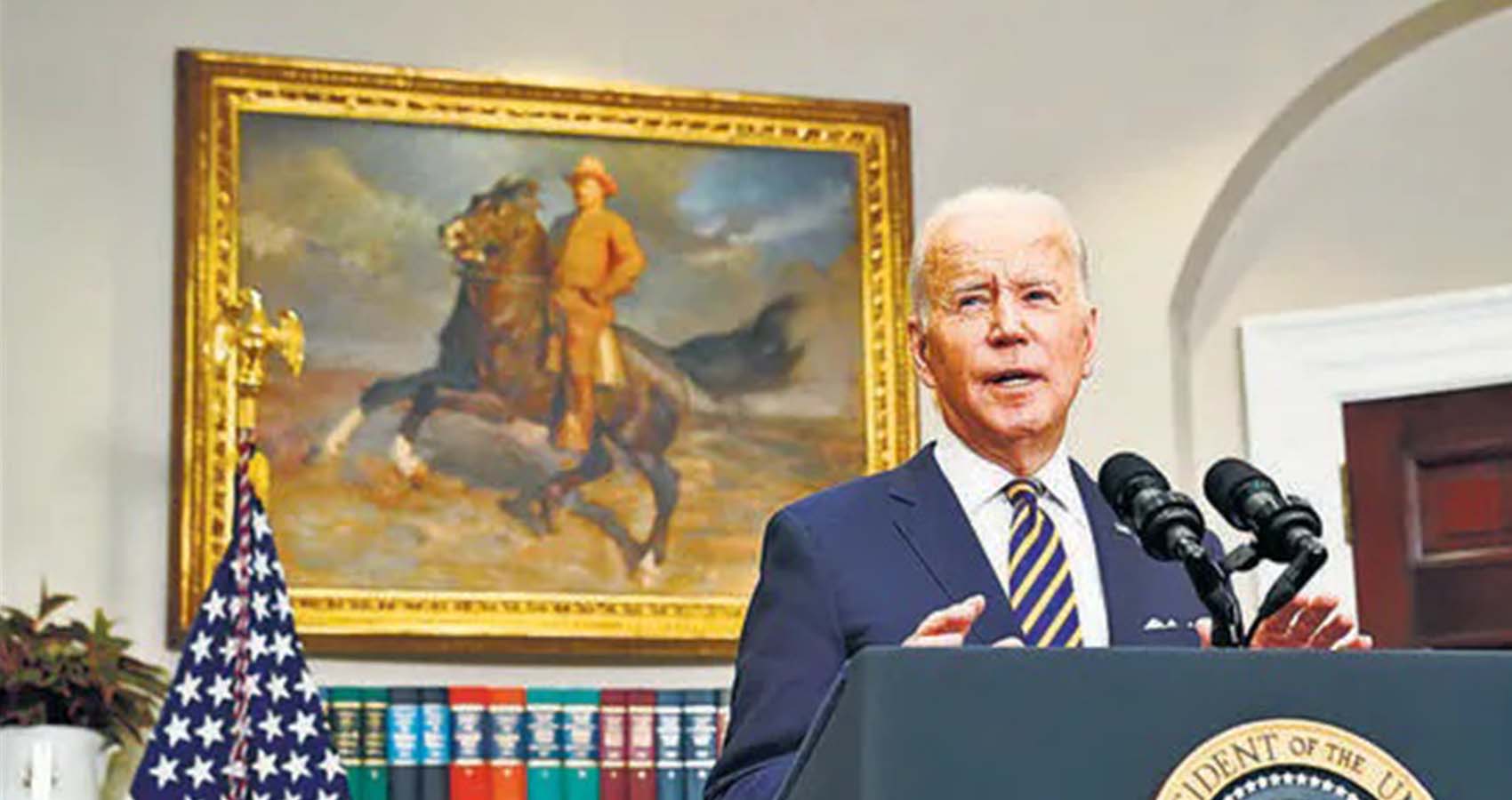

Biden told Modi during an hour-long video call Monday that the U.S. is ready to help India diversify its sources of energy, according to White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “The president also made clear that he doesn’t believe it’s in India’s interest to accelerate or increase imports of Russian energy or other commodities,” Psaki said.

Biden told Modi during an hour-long video call Monday that the U.S. is ready to help India diversify its sources of energy, according to White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “The president also made clear that he doesn’t believe it’s in India’s interest to accelerate or increase imports of Russian energy or other commodities,” Psaki said.

India’s multilingual Bollywood actor Prakash Raj has responded strongly to Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s recent remarks that Hindi should be accepted as an alternative to English. “Amit Shah ji, I want to know where do you want us to speak Hindi, learn Hindi,” asked the actor. The actor joins us on this episode of ‘Left, Right and Centre’.

India’s multilingual Bollywood actor Prakash Raj has responded strongly to Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s recent remarks that Hindi should be accepted as an alternative to English. “Amit Shah ji, I want to know where do you want us to speak Hindi, learn Hindi,” asked the actor. The actor joins us on this episode of ‘Left, Right and Centre’.

India on Saturday

India on Saturday

If Hindu unity is a facade, it also follows that the Hindu-Muslim binary, while a common framing for the discussion of Indian politics, cannot be as straightforward as it appears.

If Hindu unity is a facade, it also follows that the Hindu-Muslim binary, while a common framing for the discussion of Indian politics, cannot be as straightforward as it appears.

Politico reported last week that “As the US Senate considered making Garcetti emissary to the world’s biggest democracy, the consternation was initially confined to the GOP: Republican Iowa Sens. Joni Ernst and Chuck Grassley both placed holds on Garcetti’s nomination last month over allegations that Garcetti knew of sexual misconduct in his office, when he was the mayor of Los Angeles.

Politico reported last week that “As the US Senate considered making Garcetti emissary to the world’s biggest democracy, the consternation was initially confined to the GOP: Republican Iowa Sens. Joni Ernst and Chuck Grassley both placed holds on Garcetti’s nomination last month over allegations that Garcetti knew of sexual misconduct in his office, when he was the mayor of Los Angeles.

There will be consequences for countries looking to circumvent the US sanctions against Russia, the US warned even as Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov arrived in India last week on March 31st. Visiting US deputy NSA Daleep Singh, who was in India and is leading US efforts to sanction Russia, didn’t specify the consequences but said these were part of private discussions and the US would not like to see any country attempting to take advantage of the current situation.

There will be consequences for countries looking to circumvent the US sanctions against Russia, the US warned even as Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov arrived in India last week on March 31st. Visiting US deputy NSA Daleep Singh, who was in India and is leading US efforts to sanction Russia, didn’t specify the consequences but said these were part of private discussions and the US would not like to see any country attempting to take advantage of the current situation.

“India, as you are aware, has always been in favor of resolving differences and disputes through dialogue and diplomacy. In our meeting today, we will have an opportunity to discuss contemporary issues and concerns in some detail. I look forward to our discussions,” the External Affairs Minister said.

“India, as you are aware, has always been in favor of resolving differences and disputes through dialogue and diplomacy. In our meeting today, we will have an opportunity to discuss contemporary issues and concerns in some detail. I look forward to our discussions,” the External Affairs Minister said.

At one end, this has included delegations from the United States, Australia and Japan, the three nations which are India’s partners in the Quad, officially known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

At one end, this has included delegations from the United States, Australia and Japan, the three nations which are India’s partners in the Quad, officially known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

Earlier this week, US President Joe Biden has said that among the Quad countries, India was “somewhat shaky” in terms of showing its opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Earlier this week, US President Joe Biden has said that among the Quad countries, India was “somewhat shaky” in terms of showing its opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

US state department spokesperson Ned Price said notwithstanding India’s historic relationship with Russia, which came together at a time when the US was not prepared to have such kind of a relationship with India, now the US is a partner of India.

US state department spokesperson Ned Price said notwithstanding India’s historic relationship with Russia, which came together at a time when the US was not prepared to have such kind of a relationship with India, now the US is a partner of India.

Till now China was UAE’s largest market. With the new agreement, India will step into that place. This agreement is particularly important at a time when India is taking a strong stance against Chinese products. It is heartening to note that the UAE has not taken into consideration Pakistan which is trying to gain a better foothold there than India on considerations like religion. The agreement aims at encouraging, rejuvenating and generally improving sectors like economy, energy, weather forecasting, technology, education, food safety, health, defense and security. With the signing of the agreement, the import duties on various products will come down.

Till now China was UAE’s largest market. With the new agreement, India will step into that place. This agreement is particularly important at a time when India is taking a strong stance against Chinese products. It is heartening to note that the UAE has not taken into consideration Pakistan which is trying to gain a better foothold there than India on considerations like religion. The agreement aims at encouraging, rejuvenating and generally improving sectors like economy, energy, weather forecasting, technology, education, food safety, health, defense and security. With the signing of the agreement, the import duties on various products will come down.

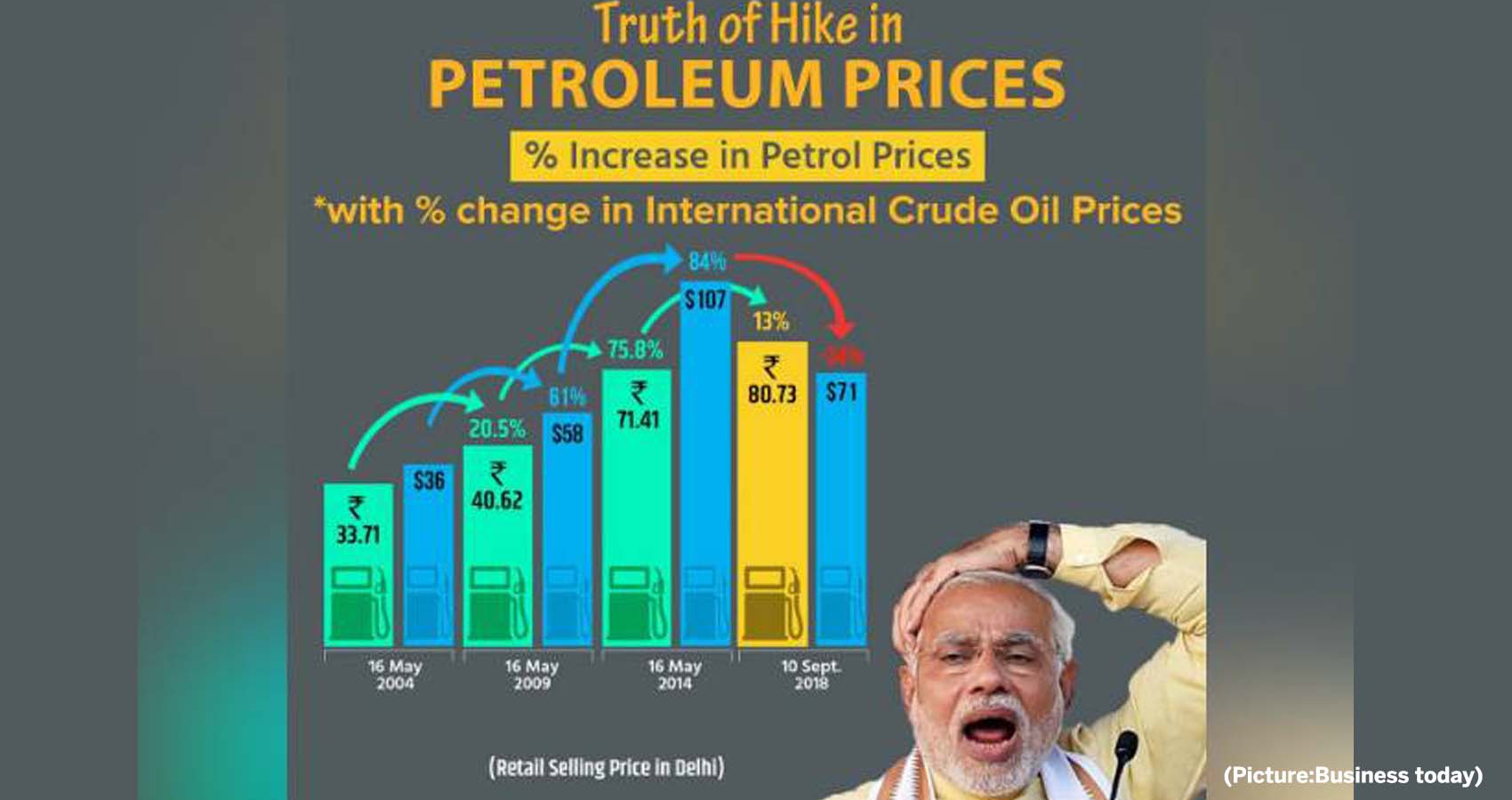

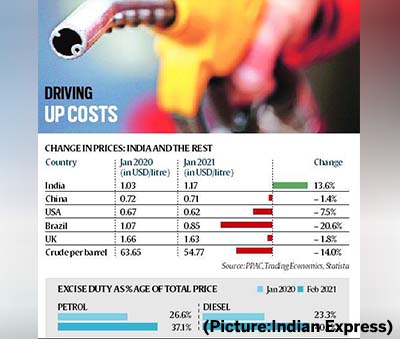

Journalists who traveled extensively into the Hindi heartland say that they found the voters constantly complaining about lack of jobs, high inflation, cooking gas, petrol prices, and many other issues. But when asked who they would vote for, their choice was unanimous: BJP. What was the rationale? They said that Modi was in for the big fight, so they wanted to support him and his party. What they meant by the big fight was Hindus versus Muslims.

Journalists who traveled extensively into the Hindi heartland say that they found the voters constantly complaining about lack of jobs, high inflation, cooking gas, petrol prices, and many other issues. But when asked who they would vote for, their choice was unanimous: BJP. What was the rationale? They said that Modi was in for the big fight, so they wanted to support him and his party. What they meant by the big fight was Hindus versus Muslims.

One such resolution was backed by 141 countries, though a Russian diplomat contended that with China and India both abstaining, the critics represented less than half of the global population.

One such resolution was backed by 141 countries, though a Russian diplomat contended that with China and India both abstaining, the critics represented less than half of the global population.

“Let me also state that we condemn all acts motivated by anti-Semitism, Christianophobia or Islamophobia. However, such phobias are not restricted to Abrahamic religions only,” he said.

“Let me also state that we condemn all acts motivated by anti-Semitism, Christianophobia or Islamophobia. However, such phobias are not restricted to Abrahamic religions only,” he said.

“Hindus everywhere need to stand up and speak up against this really poisonous variant of Hindu nationalism that threatens to destroy not just the wonderful civilization and ethos that is India, but really a lot of communities everywhere in the world,” said Prof. Rohit Chopra, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at Santa Clara University.

“Hindus everywhere need to stand up and speak up against this really poisonous variant of Hindu nationalism that threatens to destroy not just the wonderful civilization and ethos that is India, but really a lot of communities everywhere in the world,” said Prof. Rohit Chopra, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at Santa Clara University.

The results also indicate the emphasis on welfare politics in the country. While

The results also indicate the emphasis on welfare politics in the country. While

Since coming to power in 2014, Modi has sought to squeeze charities and non-profit groups that receive foreign funds. Greenpeace and Amnesty International are among the civil society groups that have had to close their offices in India.

Since coming to power in 2014, Modi has sought to squeeze charities and non-profit groups that receive foreign funds. Greenpeace and Amnesty International are among the civil society groups that have had to close their offices in India.

“It had little to do with the Soviet Union because it was about ideologies such as anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-apartheid, and pro-Palestine, which were the basis of non-allied nations. We also supported the Soviet block, “explains TP Sreenivasan, India’s former Deputy Standing Representative for the United Nations in New York. In her article, Das writes that the tendency towards the Soviet Union is likely to be partly due. “India and the former Soviet Union share a position as an economically developing country rather than an inherent idealistic affinity.”

“It had little to do with the Soviet Union because it was about ideologies such as anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-apartheid, and pro-Palestine, which were the basis of non-allied nations. We also supported the Soviet block, “explains TP Sreenivasan, India’s former Deputy Standing Representative for the United Nations in New York. In her article, Das writes that the tendency towards the Soviet Union is likely to be partly due. “India and the former Soviet Union share a position as an economically developing country rather than an inherent idealistic affinity.”

What triggered it?

What triggered it?

The resolution proposed by the US and Albania sought to declare that Russia has committed acts of aggression against Ukraine and the situation is a breach of international peace and security. It had also demanded that Russia immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine and completely withdraw its military forces from within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders.

The resolution proposed by the US and Albania sought to declare that Russia has committed acts of aggression against Ukraine and the situation is a breach of international peace and security. It had also demanded that Russia immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine and completely withdraw its military forces from within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders. India was courted by both the US and Russia given the symbolic nature of the vote and the West’s desire to isolate the US. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday. And US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to press the case for voting for the resolution.

India was courted by both the US and Russia given the symbolic nature of the vote and the West’s desire to isolate the US. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday. And US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to press the case for voting for the resolution.

U.S. President Joe Biden said on Friday he was convinced Russian President Vladimir Putin had made a decision to invade Ukraine, and though there was still room for diplomacy, he expected Russia to move on the country in the coming days. Russia has repeatedly denied preparing to invade Ukraine.

U.S. President Joe Biden said on Friday he was convinced Russian President Vladimir Putin had made a decision to invade Ukraine, and though there was still room for diplomacy, he expected Russia to move on the country in the coming days. Russia has repeatedly denied preparing to invade Ukraine.

The shock to international stability could hit global markets

The shock to international stability could hit global markets Russian cyberattacks have

Russian cyberattacks have

The document prepared mostly by the National Security Council and released a year after Biden assumed office sets out the plan for the Indo-Pacific, a region that his administration had said was going to be the focus of its diplomatic and strategic engagement.

The document prepared mostly by the National Security Council and released a year after Biden assumed office sets out the plan for the Indo-Pacific, a region that his administration had said was going to be the focus of its diplomatic and strategic engagement.

While articulating that that a new Anti-Conversion Law is not necessary since the Indian Constitution has enough provisions for the same, the signatories also stated: `Wherever the Anti-Conversion law, ironically officially called Freedom of Religion Act, was passed, it became a justification for the persecution of the minorities and other marginalized identities. The attacks on the minorities grew sharply in recent years since this law was used as a weapon targeting the dignity of Christians and Muslims particularly belonging to Adivais, Dalits and women.’ The petition called for joining hands to defend the values enshrined in the Indian Constitution and protection of human rights of the minorities and other marginalized sections in India. The petition was initiated by the National Solidarity Forum, a network of groups and individuals who started acting in response to the Kandhamal Genocide on the Adivasi Christians and Dalit Christians in 2007-2008.

While articulating that that a new Anti-Conversion Law is not necessary since the Indian Constitution has enough provisions for the same, the signatories also stated: `Wherever the Anti-Conversion law, ironically officially called Freedom of Religion Act, was passed, it became a justification for the persecution of the minorities and other marginalized identities. The attacks on the minorities grew sharply in recent years since this law was used as a weapon targeting the dignity of Christians and Muslims particularly belonging to Adivais, Dalits and women.’ The petition called for joining hands to defend the values enshrined in the Indian Constitution and protection of human rights of the minorities and other marginalized sections in India. The petition was initiated by the National Solidarity Forum, a network of groups and individuals who started acting in response to the Kandhamal Genocide on the Adivasi Christians and Dalit Christians in 2007-2008.

Over USD 230 million has been devolved through Panchayat institutions for MGNREGA, Mid-Day meals and other programs. 44 Digital village centers have been established at Gram Panchayat to provide internet access to rural areas as well as access to e-delivery of Government services. Over 70,000 ration cards were seeded with Aadhar while 50,000 families were covered under state-sponsored Health Insurance Schemes. Over 15,000 loans have been sanctioned which included 4600 loans for women entrepreneurs.

Over USD 230 million has been devolved through Panchayat institutions for MGNREGA, Mid-Day meals and other programs. 44 Digital village centers have been established at Gram Panchayat to provide internet access to rural areas as well as access to e-delivery of Government services. Over 70,000 ration cards were seeded with Aadhar while 50,000 families were covered under state-sponsored Health Insurance Schemes. Over 15,000 loans have been sanctioned which included 4600 loans for women entrepreneurs.

Stanton cites instances from his own US government. White Americans have been responsible for the virtual extermination of Native Americans and for the oppression and impoverishment of Afro-Americans through slavery. To which we might add that Americans deliberately annihilated two Japanese cities in the final stages of World War II through atomic bombing.

Stanton cites instances from his own US government. White Americans have been responsible for the virtual extermination of Native Americans and for the oppression and impoverishment of Afro-Americans through slavery. To which we might add that Americans deliberately annihilated two Japanese cities in the final stages of World War II through atomic bombing.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, played a crucial role in leading India on the path of secularism. Although Vallabhbhai Patel had huge success as the party chief, Mahatma Gandhi chose Nehru to succeed him and also as the first prime minister of the country.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, played a crucial role in leading India on the path of secularism. Although Vallabhbhai Patel had huge success as the party chief, Mahatma Gandhi chose Nehru to succeed him and also as the first prime minister of the country.

Although India embraced globalization at the turn of the 1990s, there was little domestic support for liberalizing trade. Opposing free trade agreements united the left and the right; even more powerful was the resistance from an Indian capitalist class reluctant to open its captive market for foreign producers.

Although India embraced globalization at the turn of the 1990s, there was little domestic support for liberalizing trade. Opposing free trade agreements united the left and the right; even more powerful was the resistance from an Indian capitalist class reluctant to open its captive market for foreign producers.

As far as his differences with Congress party (INC) are concerned they related more to means to be employed for getting Independence. He was twice President of INC. The difference came up mainly in the wake of Second World War when Congress under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi planned a nationwide agitation; ‘Quit India Movement’. Bose at this point of time wanted to make the British quit by allying with Germany and Japan who were Britain’s enemy countries. The majority of Congress Central committee was with Gandhi’s proposal and leaders like Patel and Nehru totally opposed the strategy proposed by Bose.

As far as his differences with Congress party (INC) are concerned they related more to means to be employed for getting Independence. He was twice President of INC. The difference came up mainly in the wake of Second World War when Congress under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi planned a nationwide agitation; ‘Quit India Movement’. Bose at this point of time wanted to make the British quit by allying with Germany and Japan who were Britain’s enemy countries. The majority of Congress Central committee was with Gandhi’s proposal and leaders like Patel and Nehru totally opposed the strategy proposed by Bose.

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, has

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, has

Earlier last month, US Senate Foreign Relations Committee chaired by Sen. Menendez, D-N.J., along with only a handful of Democrats and two Republicans, stressed how Washington sees India as a key partner in its effort to push back against China’s expanding power and influence.

Earlier last month, US Senate Foreign Relations Committee chaired by Sen. Menendez, D-N.J., along with only a handful of Democrats and two Republicans, stressed how Washington sees India as a key partner in its effort to push back against China’s expanding power and influence.

These leaders appear to be unimpressed with the vital work done by many of these civic organizations in blunting the fury of the pandemic by providing food and assistance when the government was found missing in action. Missionaries of Charity, an organization founded by Mother Teresa, is one of the impacted organizations and might have garnered the most attention. However, so many of those organizations on that list might soon be depriving a dying patient of urgent medical care due to their inability to pay or denying a meal to a hungry person from the ranks of the poor and disadvantaged.

These leaders appear to be unimpressed with the vital work done by many of these civic organizations in blunting the fury of the pandemic by providing food and assistance when the government was found missing in action. Missionaries of Charity, an organization founded by Mother Teresa, is one of the impacted organizations and might have garnered the most attention. However, so many of those organizations on that list might soon be depriving a dying patient of urgent medical care due to their inability to pay or denying a meal to a hungry person from the ranks of the poor and disadvantaged.