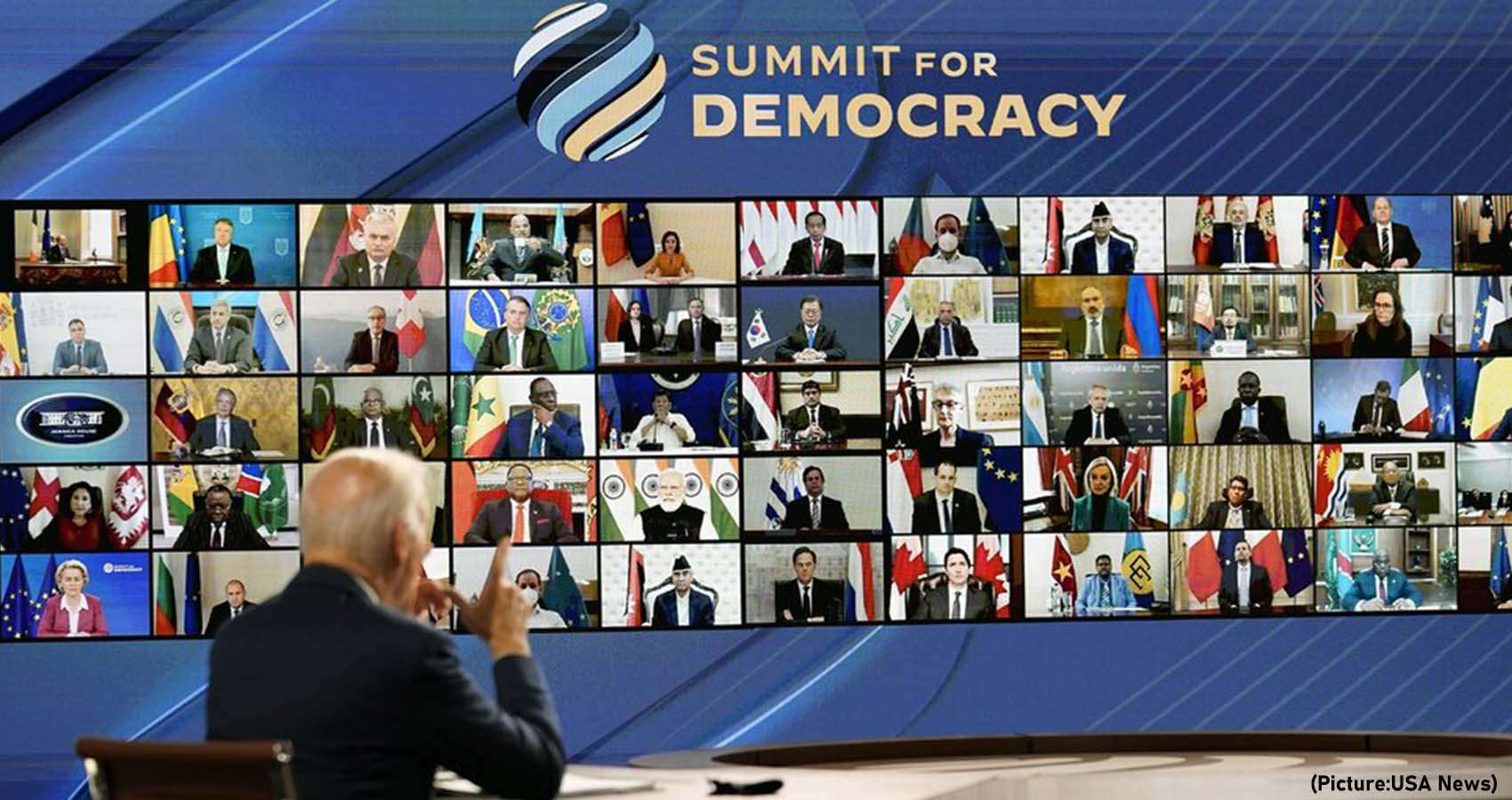

U.S. President Joe Biden is set to host a virtual summit this week for leaders from government, civil society, and the private sector to discuss the renewal of democracy. We can expect to see plenty of worthy yet predictable issues discussed: the threat of foreign agents interfering in elections, online disinformation, political polarization, and the temptation of populist and authoritarian alternatives. For the United States specifically, the role of money in politics, partisan gerrymandering, endless gridlock in Congress, and the recent voter suppression efforts targeting Black communities in the South should certainly be on the agenda.

All are important and relevant topics. Something more fundamental, however, is needed. The clear erosion of our political institutions is just the latest evidence, if any more was needed, that it’s past time to discuss what democracy means—and why we should care about it. We have to question, moreover, whether the political systems we have are even worth restoring or if we should more substantively alter them, including through profound constitutional reforms.

Such a discussion has never been more vital. The systems in place today once represented a clear improvement on prior regimes—monarchies, theocracies, and other tyrannies—but it may be a mistake to call them adherents of democracy at all. The word roughly translates from its original Greek as “people’s power.” But the people writ large doesn’t hold power in these systems. Elites do. Consider that in the United States, according to a 2014 study by the political scientist’ Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, only the richest 10 percent of the population seems to have any causal effect on public policy. The other 90 percent, they argue, is left with “democracy by coincidence”—getting what they want only when they happen to want the same thing as the people calling the shots.

Such a discussion has never been more vital. The systems in place today once represented a clear improvement on prior regimes—monarchies, theocracies, and other tyrannies—but it may be a mistake to call them adherents of democracy at all. The word roughly translates from its original Greek as “people’s power.” But the people writ large doesn’t hold power in these systems. Elites do. Consider that in the United States, according to a 2014 study by the political scientist’ Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, only the richest 10 percent of the population seems to have any causal effect on public policy. The other 90 percent, they argue, is left with “democracy by coincidence”—getting what they want only when they happen to want the same thing as the people calling the shots.

This discrepancy between reality—democracy by coincidence—and the ideal of people’s power are baked in as a result of fundamental design flaws dating back to the 18th century. The only way to rectify those mistakes is to rework the design—to fully reimagine what it means to be democratic. Tinkering at the edges won’t do.

The best starting place to rectify such flaws is to better understand how they came about. Representative government, the ancestor of modern democracies, was born in the 18th century as a classical liberal-republican construct rather than a democratic one, primarily focused on the protection of certain individual rights rather than the empowerment of the broader citizenry. The goal was to give the people some say in choosing their rulers without allowing for actual popular rule. In other words, representative government historically favored the idea of people’s consent to power over that of people’s exercise of power.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, for example, famously wanted to create a republic rather than a democracy, which they associated with mob rule. James Madison, in particular, feared the tyranny of the majority as much as he disliked and rejected the old monarchical orders. He wanted to create a mixed regime with aristocratic and popular features whose main goal would be to protect individuals as much from powerful minorities as oppressive majorities. Alexander Hamilton even defended the ideal of a government that would include a president elected for life.

The federalist founders were thus explicit in their intent to create a republic that would not rest on demos Kratos, or “people’s power,” but instead on the power of elected elites, restrained by a complex system of checks and balances. They aimed to staff representative assemblies with a natural aristocracy of talent and wisdom capable of enlarging and refining the views of common people. In this way, the system would serve as a filter, maximizing the individual competence of representatives while accepting the costs of reducing that group to a sociologically and economically homogeneous group.

The next historical step in the evolution of representative government was to go from parliamentary democracy—where the legislative assembly was seen as a place of deliberation among individually superior minds—to party democracy. Elections became a competition among policy platforms in which individual citizens or their representatives could exercise their vote.

In the process, we moved from the Madisonian view of electoral representation as a proxy for public sentiment to something quite different. Party competition was seen by some as an effective system to ensure the periodic removal of the worst political leaders or, in an even more optimistic view, as a rational battle of ideas among partisan platforms.

The move to this form of the political regime was accompanied—and buttressed—by the flattening out of social distinctions and what the French historian Alexis de Tocqueville saw as an irresistible equalization of conditions. It was during this process that we started to call modern societies and by extension their governments, democracies. This began around 1830 in the United States and France and 1870 in the United Kingdom, despite the remarkable fact that women and minorities did not get the right to vote until much later. But while there was some real but limited progress toward sociopolitical equality, actual decision-making power—over anything from economic to foreign policy—remained in the hands of the elites.

Not only is this unequal distribution and indeed concentration of power hardly compatible with the idea of democracy, but it also makes the system vulnerable to systematic failures of governance. One of the main advantages of democracy, according to thinkers from Aristotle to W.E.B. Du Bois, is its capacity, when properly institutionalized, to tap into the distributed collective wisdom of its entire public. Along these lines, Aristotle thought that two heads were better than one. More poetically, Du Bois argued that “in the people, we have the source of that endless life and unbounded wisdom which the rulers of men must-have.”

Yet by design, representative democracies only sample the wisdom of a narrow subset of the population, namely the one that wins elections. Such a subset has globally skewed male, wealthy, educated, and of the locally dominant ethnicity. One might also add the following traits: charismatic, articulate, tall, and extroverted. It is not clear that any of these qualities—undeniably useful to win electoral campaigns—have any bearing on the capabilities of our ruling class to legislate well. This is especially problematic if, as some social scientists argue, the collective competence of a group is only partially a function of individual qualities and more so a function of the group’s diversity. Parliaments as we staff them might well be too homogenous for good lawmaking. Meanwhile, the rest of the population—including the introverted, inarticulate, short, and shy, as well as, typically, poor and Black or other people of color—is left to opine, at best, from a distance, if they don’t retreat from the system altogether.

While there is some wisdom to be gained from the aggregation of popular judgment in elections, pure electoral democracy misses out on all that can be gained from the diversity of knowledge and insight among the broader population. The key is to involve that broader group of people in a more deliberative and participatory way. Leaving them out creates massive blind spots, simmering resentment, and a systematic failure to address the needs and preferences of a portion, sometimes even a majority, of the population.

Examples of such failures abound, from the plight of the suburban working class in most advanced industrial societies, which is vastly underrepresented in all Western parliaments, to that of Black Americans, who are also still underrepresented in the U.S. Congress.

Such areas of underrepresentation might explain political events that surprised our pundit class: U.S. President Donald Trump’s electoral victory, the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom, and the yellow vest rebellion against a tax on gas in France. The example of the yellow vests, or gilets jaunes, offers a textbook case of the inability of electoral institutions to respond to the interests and concerns of a significant portion of the population that feels invisible—hence, the neon yellow jackets—and has in some cases given up on voting altogether.

These democratic flaws at the heart of representative democracy are sufficiently serious to account for at least some of its current institutional crisis, which may be better described as a chronic illness due to a congenital defect. Perhaps other factors, such as globalization, unfettered capitalism, and rapid technological change, as well as the economic inequalities they entail, made things worse in some countries. But make no mistake: Each of these vulnerabilities is part of the initial design.

Some may see this essay as a call for revolution. It is not. We have inherited the legacies of the 18th century, both institutional and ideological, and we should figure out how to make do with them, at least in part and for the time being. Yet having a clearer idea of what an authentic democracy should look like can usefully guide institutional reform in more radical directions—ones that are compatible with current power structures and prevailing ways of thinking.

Wherever possible, we should build new models of democratic decision-making so they can nudge the old ones aside as those become obsolete. That, I believe, is our best hope for renewing democracy.

There are many proposals for what a true democracy should look like, and they are all worth debating. My view defended in my book Open Democracy, is that an authentic democracy would center on ordinary citizens rather than elected politicians. One way forward, therefore, is to break with the dogma of electoral representation as the only—let alone the most democratic—a form of representation.

If democracy is truly ruled by the people, then all of us should be able to represent and be represented in turn—that is, have an equal chance to engage in lawmaking and policymaking on behalf of the rest of the group. The ruling, in other words, should not be a job reserved for those who can win elections. It should be accessible to all.

The open democracy I envisage would center on a House of the People selected by a randomized civic lottery—a large-scale jury, if you will—in which ordinary citizens have a chance to participate as democratic representatives with legislative prerogatives of their own (for example, on climate change and other long-term issues that remain largely unaddressed by our current political systems). Such a body could replace—or at the very least complement—existing elected chambers. This House of the People would be a forum for nonpartisan, informed, and transparent deliberation.

Furthermore, such a body should be open to the input of the larger public, including through mechanisms that enable individuals to put issues on its agenda or trigger a referendum on its proposals or even convene a citizens’ assembly—a large body of randomly selected citizens gathered to deliberate about a specific issue.

Critics of this idea might argue that putting ordinary citizens at the center of our democratic process naively assumes that politics is an amateurs’ sport. To some extent, that is correct because having a say about the common good and defining the law that governs all of us should be open to all, regardless of class, gender, age, race, education levels, or other characteristics. Only once we acknowledge that fact can we both live up to the ideal of political equality and tap the collective intelligence of the whole.

But more importantly, when given the proper resources and the same access to experts that elected officials routinely enjoy, the so-called amateurs can cultivate skills and legislate well. The proof of concept here is provided not just by the example of ancient Athens, which essentially functioned based on open assemblies and randomly selected councils and juries, but the modern-day as well. Ordinary citizens in recent times have demonstrated their competence on all kinds of issues, from the more technical, as with the 2004 Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform in the Canadian province of British Columbia, to the more controversial, as with the 2012 Constitutional Convention and 2016 Citizens’ Assembly in Ireland, which deliberated on marriage equality and abortion, respectively.

In 2019, in a landmark case given the size and diversity of the country, French President Emmanuel Macron entrusted 150 randomly selected citizens with the task of generating bills to curb greenhouse gas emissions in ways that align with social justice. After nine months of hard work, and in consultation with experts, they succeeded. While foreign policy has only been put on the agenda of citizens’ assemblies a few times, there is no reason to think that ordinary citizens would be less equipped to make decisions on these issues as well. Particularly when it comes to decisions related to starting or ending wars, it would seem both fair and smart to involve a much more representative sample of all affected interests.

Just as in an elected parliament, citizen legislators should avail themselves of existing knowledge. They should be served by a loyal bureaucracy and have easy access to experts. And these bureaucrats and experts should be put “on tap, not on top,” to use a phrase common in deliberative democracy circles—meaning they are available to advise but are not the decision-makers. In addition, assemblies of citizen legislators, just like parliaments, should be autonomous and self-ruling, including in the choice of experts appearing in front of them.

If those conditions are in place, the risk that the House of the People could be captured by technocrats and bureaucrats is not nil, but it is arguably less than in existing systems where elected officials are so busy raising funds and campaigning that they have every incentive to delegate the actual business of legislating to others.

What about accountability, you might ask? Accountability is an overused and underdefined term that we have come to identify within the very process of modern politics. After all, we should be able to remove elected officials who have underperformed. But elections can be a blunt and not particularly effective tool. There are other ways to sanction people for disappointing or wrongful use of power. More importantly, accountability has a broader meaning: the presentation of accounts, namely justifications for the laws and policies imposed on the population. Deliberative assemblies of ordinary citizens are a much better place than elected parliaments to generate such explanations.

What about the democratic legitimacy of randomly selected legislatures? This objection shows how much our political intuitions are shaped by the historical centrality of elections. Yet consider juries, the democratic institution par excellence according to Tocqueville. Do jury members lack democratic legitimacy because they have been selected by lot rather than elected? No. The intuition of our current system, in which we emphasize the exercise of power rather than the consent to power, is that the democratic legitimacy of jury members comes from the fact that they could be any one of us. We could be them. But what this example shows is that elections are not strictly necessary for either democratic representation or democratic legitimacy.

Does an open democracy still sound like science fiction or perhaps like a dated vision of politics only fit for small and homogenous Greek city-states? Only if you ignore the now close to 600 examples of randomly selected deliberative bodies documented at the local, regional, national, and international levels in the last 40 years, according to data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

While such bodies often face resistance on the part of existing structures, which tend to view them as competition, several have had an important impact. Deliberative polls conducted by electric utilities in Texas between 1996 and 1998 were largely responsible for a major reversal in the state’s energy policy, turning it from a pure oil and gas state into a leader in green energy. The Irish citizens’ assemblies on marriage equality, abortion, blasphemy, and the right to divorce have all led to constitutional changes, and the Irish Citizens’ Assembly on climate led to the recently enacted Climate Act. In France, despite much resistance from Parliament, between 10 and 50 percent of the Citizens’ Convention on Climate’s recommendations were incorporated into real law, producing the most ambitious French climate bill to date. In fact, in 81 percent of the 55 examples of randomly selected bodies for which OECD data is available, public authorities accepted at least half of the recommendations that citizens developed in these processes.

The next phase of democratic transformation is to build more empowered, permanent citizens’ assemblies with legislative capabilities of their own. This has already begun. Examples include the region of East Belgium, which inaugurated the first permanent Citizens’ Council with agenda-setting power in 2019, and the city of Paris, which just convened a similar council of 100 Parisians, with more power still.

It might take a while before a country gives so much power to citizens at the national level. But it is worth noting that France briefly toyed with the idea of replacing its third legislative chamber, a largely symbolic advisory body where representatives of organized civil society currently convene, with a Chamber of Citizen Participation. Various scholars and activists have called for abolishing upper chambers seen as corrupt or out of dates, such as the Canadian Senate or the House of Lords in the United Kingdom, with so-called “legislatures by lot.” What might have seemed like radical thinking a few years ago is now entering the realm of the possible.

First, the summit needs to question and broaden the definition of democracy. If the aim of pro-democracy forces is simply to return to some imagined pre-Trump or pre-Brexit utopia, then we will have learned nothing. If the solution is simply to empower courts and raise supermajority thresholds to try to protect the system against populist surges, then we will possibly worsen the problem caused by elitism and democratic deficits in the first place. Returning to the core idea of people’s power—and interrogating the conditions under which the wisdom of the many can be channeled into law and policymaking—should be the starting point of any conversation.

The second pitfall to avoid is holding a summit on democracy that is itself elitist and exclusionary. The only invitees, as far as we know, are more than 100 world leaders, who are likely to be very educated, wealthy, and rather old. Just as this year’s U.N. Climate Change Conference, known as COP26, (and all 25 before it) failed to be truly inclusive and representative of the diversity of climate interests and concerns around the world, summits that only gather people from the top of various social, economic, political, and other hierarchies are premised on a flawed idea of what produces collective wisdom. As a result, it risks reproducing the blind spots that yielded the world’s democratic crisis in the first place.

Democratic leadership can come from surprising places. I would hope the summit organizers at the very least invite participants from former citizens’ assemblies, who could bring a diversity of background as well as unique perspectives on a different kind of democratic politics. Better yet, they could start thinking about institutionalizing the principle of an international citizens’ assembly for the summit’s next iterations, as several thinkers, including myself, have called for in a joint letter to Biden. Such an assembly could follow the model of the Global Assembly on the climate crisis, which ran in parallel to the COP26 meeting in Glasgow, Scotland.

Finally, when it comes to the situation in the United States, one hopes that Biden’s summit will be an opportunity to change the country’s mostly sterile public conversation about democracy. Americans must finally allow themselves to question the foundations of the Constitution they so uncritically worship. The achievements of the Founding Fathers, as brilliant as they were, need to be reassessed in light of more than two centuries of dramatic change and a wealth of new social scientific knowledge. If we are to overcome the many profound challenges we face today, we need to be as bold and visionary in our time as they were in theirs.

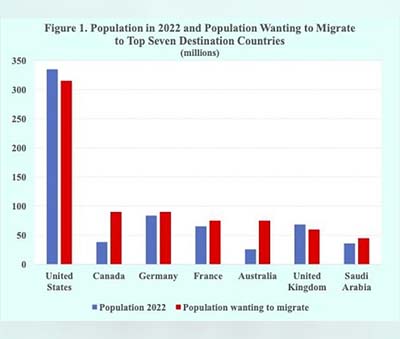

Seven destination countries attract half of those wanting to migrate to another country. The top destination country at 21 percent of those wanting to migrate is the United States. Substantially lower, Canada and Germany are next at 6 percent, followed by France and Australia at 5 percent, the United Kingdom at 4 percent, and Saudi Arabia at 3 percent

Seven destination countries attract half of those wanting to migrate to another country. The top destination country at 21 percent of those wanting to migrate is the United States. Substantially lower, Canada and Germany are next at 6 percent, followed by France and Australia at 5 percent, the United Kingdom at 4 percent, and Saudi Arabia at 3 percent

Boris Johnson, whose premiership has been engulfed in scandal for months after it emerged he attended illegal parties during lockdown — and who subsequently, became the first sitting UK Prime Minister to be found guilty of breaking the law — was able to appear at legitimate gatherings outside Buckingham Palace on Saturday and Sunday, enjoying a brief respite from the constant speculation about his job security.

Boris Johnson, whose premiership has been engulfed in scandal for months after it emerged he attended illegal parties during lockdown — and who subsequently, became the first sitting UK Prime Minister to be found guilty of breaking the law — was able to appear at legitimate gatherings outside Buckingham Palace on Saturday and Sunday, enjoying a brief respite from the constant speculation about his job security.

Modi’s party took no action against the two BJP leaders until Sunday, when a sudden chorus of diplomatic outrage began with Qatar and Kuwait summoning their Indian ambassadors to protest. The BJP suspended Sharma and expelled Jindal and issued a rare statement saying it “strongly denounces insult of any religious personalities,” a move that was welcomed by Qatar and Kuwait.

Modi’s party took no action against the two BJP leaders until Sunday, when a sudden chorus of diplomatic outrage began with Qatar and Kuwait summoning their Indian ambassadors to protest. The BJP suspended Sharma and expelled Jindal and issued a rare statement saying it “strongly denounces insult of any religious personalities,” a move that was welcomed by Qatar and Kuwait.

“From Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia; Jews in Europe; Baha’is in Iran; Christians in North Korea, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia; Muslims in Burma and China; Catholics in Nicaragua; and atheists and humanists around the world, no community has been immune from these abuses,” he said.

“From Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia; Jews in Europe; Baha’is in Iran; Christians in North Korea, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia; Muslims in Burma and China; Catholics in Nicaragua; and atheists and humanists around the world, no community has been immune from these abuses,” he said.

At the

At the  Over the last few months, India has also preserved its close ties to Russia by repeatedly

Over the last few months, India has also preserved its close ties to Russia by repeatedly

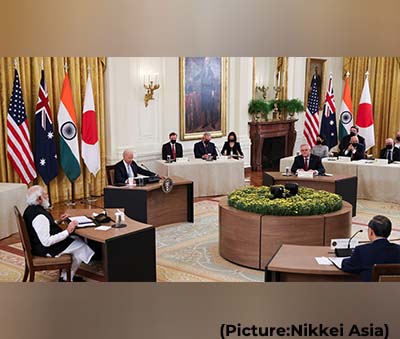

“We, the leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, convened today in person as “the Quad” for the first time. On this historic occasion we recommit to our partnership, and to a region that is a bedrock of our shared security and prosperity—a free and open Indo-Pacific, which is also inclusive and resilient.”

“We, the leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, convened today in person as “the Quad” for the first time. On this historic occasion we recommit to our partnership, and to a region that is a bedrock of our shared security and prosperity—a free and open Indo-Pacific, which is also inclusive and resilient.”

The prospect of upsetting Washington should be particularly concerning for Indian policymakers. The United States has become one of New Delhi’s most important partners, particularly as India tries to stand up to Chinese aggression in the Himalayas. But although Washington is not happy that New Delhi has refused to condemn Russian aggression, Indian policymakers have calculated that their country is so central to U.S. efforts to counterbalance China that India will remain immune to a potential backlash. So far, they’ve been right; the United States has issued only muted criticisms of Indian neutrality. Yet Washington’s patience is not endless, and the longer Russia prosecutes its war without India changing its position, the more likely the United States will be to view India as an unreliable partner. It may not want to, but ultimately New Delhi will have to pick between Russia and the West.

The prospect of upsetting Washington should be particularly concerning for Indian policymakers. The United States has become one of New Delhi’s most important partners, particularly as India tries to stand up to Chinese aggression in the Himalayas. But although Washington is not happy that New Delhi has refused to condemn Russian aggression, Indian policymakers have calculated that their country is so central to U.S. efforts to counterbalance China that India will remain immune to a potential backlash. So far, they’ve been right; the United States has issued only muted criticisms of Indian neutrality. Yet Washington’s patience is not endless, and the longer Russia prosecutes its war without India changing its position, the more likely the United States will be to view India as an unreliable partner. It may not want to, but ultimately New Delhi will have to pick between Russia and the West.

India’s trade deficit with China continued to grow, from $44 billion in 2020-21 to $72.91 billion in 2021-22. The US is, however, one of the few countries with which India has a trade surplus. In 2021-22, India recorded a positive trade balance of $32.8 billion with the US.

India’s trade deficit with China continued to grow, from $44 billion in 2020-21 to $72.91 billion in 2021-22. The US is, however, one of the few countries with which India has a trade surplus. In 2021-22, India recorded a positive trade balance of $32.8 billion with the US.

On average, Americans give more correct than incorrect answers to the 12 questions in the study. The mean number of correct answers is 6.3, while the median is 7. But the survey finds that levels of international knowledge vary based on who is answering. Americans with more education tend to score higher, for example, than those with less formal education. Men also tend to get more questions correct than women. Older Americans and those who are more interested in foreign policy also tend to perform better.

On average, Americans give more correct than incorrect answers to the 12 questions in the study. The mean number of correct answers is 6.3, while the median is 7. But the survey finds that levels of international knowledge vary based on who is answering. Americans with more education tend to score higher, for example, than those with less formal education. Men also tend to get more questions correct than women. Older Americans and those who are more interested in foreign policy also tend to perform better.

Boosted by his victory, Macron figures to be in the spotlight when he pays an expected visit to Berlin in the coming days to meet with new Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who has had a low-profile debut on the international stage. French presidents traditionally make their first post-election trip abroad to Germany as a celebration of the countries’ friendship after multiple wars.

Boosted by his victory, Macron figures to be in the spotlight when he pays an expected visit to Berlin in the coming days to meet with new Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who has had a low-profile debut on the international stage. French presidents traditionally make their first post-election trip abroad to Germany as a celebration of the countries’ friendship after multiple wars.

Advances in offensive capabilities have, however, been matched in increasingly sophisticated sensing, tracking and processing technologies designed to detect, prevent and in some cases respond to a nuclear strike – often using Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Advances in offensive capabilities have, however, been matched in increasingly sophisticated sensing, tracking and processing technologies designed to detect, prevent and in some cases respond to a nuclear strike – often using Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Though the Indian side stated that it would demonstrate the same speed and urgency that it did in concluding recent FTAs with the UAE and Australia in recent months, yet nothing can’t be said for sure about an Indo-UK FTA, as there are many thorny issues on both sides.

Though the Indian side stated that it would demonstrate the same speed and urgency that it did in concluding recent FTAs with the UAE and Australia in recent months, yet nothing can’t be said for sure about an Indo-UK FTA, as there are many thorny issues on both sides.

The sprawling Azovstal site has been almost completely destroyed by Russian attacks, but it is the last pocket of organized Ukrainian resistance in Mariupol. An estimated 2,000 soldiers and 1,000 civilians are said to be holed up in fortified positions underneath the wrecked structures.

The sprawling Azovstal site has been almost completely destroyed by Russian attacks, but it is the last pocket of organized Ukrainian resistance in Mariupol. An estimated 2,000 soldiers and 1,000 civilians are said to be holed up in fortified positions underneath the wrecked structures.

Dr. Shivangi is of the opinion that “It is apt time India should think alternative suppliers source. What can be a better source than US? We have a great opportunity here as our Senior Senator from Mississippi has been elected as a Ranking member of the US Armed Service Committee of the US Senate. With his assistance and good offices, especially after 2+2 summit, I hope and look forward to such increased collaboration with the successful Indo pacific QUAD treaty.

Dr. Shivangi is of the opinion that “It is apt time India should think alternative suppliers source. What can be a better source than US? We have a great opportunity here as our Senior Senator from Mississippi has been elected as a Ranking member of the US Armed Service Committee of the US Senate. With his assistance and good offices, especially after 2+2 summit, I hope and look forward to such increased collaboration with the successful Indo pacific QUAD treaty.

“Let us all commit ourselves to imploring peace, from our balconies and in our streets,″ Francis said. ”May the leaders of nations hear people’s plea for peace.”

“Let us all commit ourselves to imploring peace, from our balconies and in our streets,″ Francis said. ”May the leaders of nations hear people’s plea for peace.”

The Center examined all cases in the UNHCR’s database since 1960 where there were at least 500,000 refugees and similarly displaced people from a given country in a given year. The analysis doesn’t include “internally displaced persons” – those who have fled or been forced from their usual homes but haven’t yet crossed an international border. (Earlier this week, UNHCR head Filippo Grandi estimated that, all told,

The Center examined all cases in the UNHCR’s database since 1960 where there were at least 500,000 refugees and similarly displaced people from a given country in a given year. The analysis doesn’t include “internally displaced persons” – those who have fled or been forced from their usual homes but haven’t yet crossed an international border. (Earlier this week, UNHCR head Filippo Grandi estimated that, all told,

Biden told Modi during an hour-long video call Monday that the U.S. is ready to help India diversify its sources of energy, according to White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “The president also made clear that he doesn’t believe it’s in India’s interest to accelerate or increase imports of Russian energy or other commodities,” Psaki said.

Biden told Modi during an hour-long video call Monday that the U.S. is ready to help India diversify its sources of energy, according to White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “The president also made clear that he doesn’t believe it’s in India’s interest to accelerate or increase imports of Russian energy or other commodities,” Psaki said.

Khan’s party also submitted papers nominating the former foreign minister as a candidate, saying their members of parliament would resign en masse should he lose, potentially creating the need for urgent by-elections for their seats. Khan, the first Pakistani prime minister to be ousted by a no confidence vote, had clung on for almost a week after a united opposition first tried to remove him.

Khan’s party also submitted papers nominating the former foreign minister as a candidate, saying their members of parliament would resign en masse should he lose, potentially creating the need for urgent by-elections for their seats. Khan, the first Pakistani prime minister to be ousted by a no confidence vote, had clung on for almost a week after a united opposition first tried to remove him.

India on Saturday

India on Saturday

Do Ukrainians still have different views regarding politicians, economic development, and even the state of their foreign policy? Yes, absolutely, as any other democratic nation should.

Do Ukrainians still have different views regarding politicians, economic development, and even the state of their foreign policy? Yes, absolutely, as any other democratic nation should.

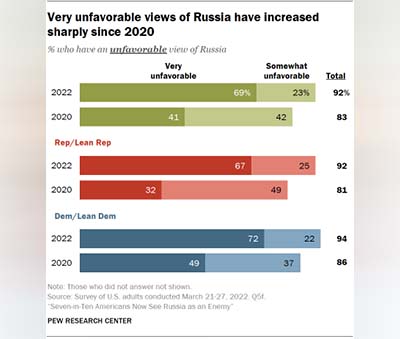

While negative sentiment toward Russia has increased substantially among both Democrats and Republicans since 2020, Republicans’ views have changed more drastically. Around a third of Republicans and Republican leaners had a very unfavorable view of Russia in 2020, compared with 67% who now hold this view – a 35 percentage point increase. In the same period, the share of Democrats with a very negative view of Russia increased by 23 points. A small partisan gap in views of Russia remains, but Republicans and Democrats are not as divided on Russia as they once were.

While negative sentiment toward Russia has increased substantially among both Democrats and Republicans since 2020, Republicans’ views have changed more drastically. Around a third of Republicans and Republican leaners had a very unfavorable view of Russia in 2020, compared with 67% who now hold this view – a 35 percentage point increase. In the same period, the share of Democrats with a very negative view of Russia increased by 23 points. A small partisan gap in views of Russia remains, but Republicans and Democrats are not as divided on Russia as they once were. Americans of all ages tend to have favorable opinions of NATO overall, but those ages 65 and older are more likely to hold a favorable view of NATO than younger adults. Roughly three-quarters (73%) of older Americans have a positive opinion of the organization, compared with 64% of those ages 18 to 29. Eight-in-ten of those with a postgraduate degree express a favorable opinion of NATO – significantly more than the share with a bachelor’s degree (73%), some college (64%) or a high school degree or less (59%).

Americans of all ages tend to have favorable opinions of NATO overall, but those ages 65 and older are more likely to hold a favorable view of NATO than younger adults. Roughly three-quarters (73%) of older Americans have a positive opinion of the organization, compared with 64% of those ages 18 to 29. Eight-in-ten of those with a postgraduate degree express a favorable opinion of NATO – significantly more than the share with a bachelor’s degree (73%), some college (64%) or a high school degree or less (59%).

Some countries tried to expel South Africa, which was one of the 51 founding members of the United Nations in 1945, because of its policy of apartheid, but the three permanent members of the Security Council – France, UK, and US – used their veto power to block that move.

Some countries tried to expel South Africa, which was one of the 51 founding members of the United Nations in 1945, because of its policy of apartheid, but the three permanent members of the Security Council – France, UK, and US – used their veto power to block that move.

“However, analysts of all stripes are not as confident in a Macron victory as they were merely a week ago. In 2017, Le Pen lost to Macron by 34 percentage points. Now, polls on the second-round place her at 46% versus Macron at 54%. This is close enough to elicit worry.

“However, analysts of all stripes are not as confident in a Macron victory as they were merely a week ago. In 2017, Le Pen lost to Macron by 34 percentage points. Now, polls on the second-round place her at 46% versus Macron at 54%. This is close enough to elicit worry.

Less than a day from a no-confidence vote that will almost certainly remove him from office, Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan said that he would not accept the result of the vote, dismissing it as part of an American conspiracy against him and setting the stage for the country’s political crisis to drag on far beyond Sunday, as Khan fights to remain in politics, New York Timers reported.

Less than a day from a no-confidence vote that will almost certainly remove him from office, Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan said that he would not accept the result of the vote, dismissing it as part of an American conspiracy against him and setting the stage for the country’s political crisis to drag on far beyond Sunday, as Khan fights to remain in politics, New York Timers reported.

His proposal for peace with India had a wider meaning as he indirectly suggested to have some sort of trilateral dialogue involving India, Pakistan and China to create an inclusive peace, as he said that apart from the Kashmir dispute, the India-China border dispute is also a matter of great concern for Pakistan and “we want it to be settled quickly through dialogue and diplomacy.” “I believe it is time for the political leadership of the region to rise above their emotional and perceptual biases and break the shackles of history to bring peace and prosperity to almost three billion people of the region,” Gen. Bajwa said.

His proposal for peace with India had a wider meaning as he indirectly suggested to have some sort of trilateral dialogue involving India, Pakistan and China to create an inclusive peace, as he said that apart from the Kashmir dispute, the India-China border dispute is also a matter of great concern for Pakistan and “we want it to be settled quickly through dialogue and diplomacy.” “I believe it is time for the political leadership of the region to rise above their emotional and perceptual biases and break the shackles of history to bring peace and prosperity to almost three billion people of the region,” Gen. Bajwa said.

At one end, this has included delegations from the United States, Australia and Japan, the three nations which are India’s partners in the Quad, officially known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

At one end, this has included delegations from the United States, Australia and Japan, the three nations which are India’s partners in the Quad, officially known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

How will these historic measures play out? Economic sanctions rarely succeed at achieving their goals. Western policymakers frequently assume that failures stem from weaknesses in sanctions design.

How will these historic measures play out? Economic sanctions rarely succeed at achieving their goals. Western policymakers frequently assume that failures stem from weaknesses in sanctions design.

Earlier this week, US President Joe Biden has said that among the Quad countries, India was “somewhat shaky” in terms of showing its opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Earlier this week, US President Joe Biden has said that among the Quad countries, India was “somewhat shaky” in terms of showing its opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Till now China was UAE’s largest market. With the new agreement, India will step into that place. This agreement is particularly important at a time when India is taking a strong stance against Chinese products. It is heartening to note that the UAE has not taken into consideration Pakistan which is trying to gain a better foothold there than India on considerations like religion. The agreement aims at encouraging, rejuvenating and generally improving sectors like economy, energy, weather forecasting, technology, education, food safety, health, defense and security. With the signing of the agreement, the import duties on various products will come down.

Till now China was UAE’s largest market. With the new agreement, India will step into that place. This agreement is particularly important at a time when India is taking a strong stance against Chinese products. It is heartening to note that the UAE has not taken into consideration Pakistan which is trying to gain a better foothold there than India on considerations like religion. The agreement aims at encouraging, rejuvenating and generally improving sectors like economy, energy, weather forecasting, technology, education, food safety, health, defense and security. With the signing of the agreement, the import duties on various products will come down.

The Center examined all cases in the UNHCR’s database since 1960 where there were at least 500,000 refugees and similarly displaced people from a given country in a given year. The analysis doesn’t include “internally displaced persons” – those who have fled or been forced from their usual homes but haven’t yet crossed an international border. (Earlier this week, UNHCR head Filippo Grandi estimated that, all told,

The Center examined all cases in the UNHCR’s database since 1960 where there were at least 500,000 refugees and similarly displaced people from a given country in a given year. The analysis doesn’t include “internally displaced persons” – those who have fled or been forced from their usual homes but haven’t yet crossed an international border. (Earlier this week, UNHCR head Filippo Grandi estimated that, all told,  Afghanistan, which has been at war either with itself or with outside forces for more than four decades, has had more than 2 million refugees every year since 1981. The peak year was 1990, after Soviet troops had withdrawn from the country and the USSR-backed government was battling to hang onto power against a coalition of mujahedeen groups. That year, more than half the country’s total estimated population – 6.3 million people – were listed as refugees.

Afghanistan, which has been at war either with itself or with outside forces for more than four decades, has had more than 2 million refugees every year since 1981. The peak year was 1990, after Soviet troops had withdrawn from the country and the USSR-backed government was battling to hang onto power against a coalition of mujahedeen groups. That year, more than half the country’s total estimated population – 6.3 million people – were listed as refugees.

As millions of people in Ukraine face hunger and dwindling supplies of water and medicine, I am announcing today that the United Nations will allocate a further $40 million from the Central Emergency Response Fund to ramp up vital assistance to reach the most vulnerable, as we wait for the nations to come.

As millions of people in Ukraine face hunger and dwindling supplies of water and medicine, I am announcing today that the United Nations will allocate a further $40 million from the Central Emergency Response Fund to ramp up vital assistance to reach the most vulnerable, as we wait for the nations to come.

Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse said in a report, “We are witnessing the birth of Bretton Woods III – a new world (monetary) order centred around commodity-based currencies in the East that will likely weaken the Eurodollar system and also contribute to inflationary forces in the West.”

Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse said in a report, “We are witnessing the birth of Bretton Woods III – a new world (monetary) order centred around commodity-based currencies in the East that will likely weaken the Eurodollar system and also contribute to inflationary forces in the West.”

In fact, the Russians were talking about a hysteria of the West for fear of the annexation of Ukraine which, they said, was never on their mind, but only a fiction of the hysterical minds of the West. And then came the onslaught on Ukraine and the Ukrainians, turning the seeming glimmer of goodness and hope into a lie. And what a lie it was! The reports are that, as I am writing this, over 2 million of Ukrainian refugees have sought refuge in neighbouring countries like Poland, Moldova, Lithuania, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania. Besides, millions of people have been displaced within the country, and they are going about helplessly trying to find a safe place for themselves.

In fact, the Russians were talking about a hysteria of the West for fear of the annexation of Ukraine which, they said, was never on their mind, but only a fiction of the hysterical minds of the West. And then came the onslaught on Ukraine and the Ukrainians, turning the seeming glimmer of goodness and hope into a lie. And what a lie it was! The reports are that, as I am writing this, over 2 million of Ukrainian refugees have sought refuge in neighbouring countries like Poland, Moldova, Lithuania, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania. Besides, millions of people have been displaced within the country, and they are going about helplessly trying to find a safe place for themselves.

Withdrawal of major Western transnational companies – such as Shell, McDonald’s and Apple – will undoubtedly hurt many Russians – not only oligarchs, their ostensible target.

Withdrawal of major Western transnational companies – such as Shell, McDonald’s and Apple – will undoubtedly hurt many Russians – not only oligarchs, their ostensible target.

“Let me also state that we condemn all acts motivated by anti-Semitism, Christianophobia or Islamophobia. However, such phobias are not restricted to Abrahamic religions only,” he said.

“Let me also state that we condemn all acts motivated by anti-Semitism, Christianophobia or Islamophobia. However, such phobias are not restricted to Abrahamic religions only,” he said.

The city has now been subjected to nine days of heavy bombardment by Russian forces, destroying apartment buildings and flattening residential areas. Footage verified by the BBC showed shelling on Thursday, confirming a statement by the city council that the bombardment was ongoing.

The city has now been subjected to nine days of heavy bombardment by Russian forces, destroying apartment buildings and flattening residential areas. Footage verified by the BBC showed shelling on Thursday, confirming a statement by the city council that the bombardment was ongoing.

Even if Putin’s actions don’t immediately push him from power, the war in Ukraine creates long-term vulnerabilities. Punishing

Even if Putin’s actions don’t immediately push him from power, the war in Ukraine creates long-term vulnerabilities. Punishing

“It had little to do with the Soviet Union because it was about ideologies such as anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-apartheid, and pro-Palestine, which were the basis of non-allied nations. We also supported the Soviet block, “explains TP Sreenivasan, India’s former Deputy Standing Representative for the United Nations in New York. In her article, Das writes that the tendency towards the Soviet Union is likely to be partly due. “India and the former Soviet Union share a position as an economically developing country rather than an inherent idealistic affinity.”

“It had little to do with the Soviet Union because it was about ideologies such as anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-apartheid, and pro-Palestine, which were the basis of non-allied nations. We also supported the Soviet block, “explains TP Sreenivasan, India’s former Deputy Standing Representative for the United Nations in New York. In her article, Das writes that the tendency towards the Soviet Union is likely to be partly due. “India and the former Soviet Union share a position as an economically developing country rather than an inherent idealistic affinity.”

“The President felt it was a constructive conversation,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters at her daily news conference.

“The President felt it was a constructive conversation,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters at her daily news conference.

The crisis unfolded after Grossi earlier in the week expressed grave concern that the fighting could cause accidental damage to Ukraine’s 15 nuclear reactors at four plants around the country.

The crisis unfolded after Grossi earlier in the week expressed grave concern that the fighting could cause accidental damage to Ukraine’s 15 nuclear reactors at four plants around the country.

“The unthinkable might start to become thinkable,”

“The unthinkable might start to become thinkable,”

Cuba had spoken in Russia’s defense on Tuesday, with Ambassador Pedro Luis Cuesta blaming the crisis on what he said is the U.S. determination to keep expanding NATO toward Russia’s borders and on the delivery of modern weapons to Ukraine, ignoring Russia’s concerns for its own security. He told the assembly the resolution “suffers from lack of balance” and doesn’t begin to address the concerns of both parties, or “the responsibility of those who took aggressive actions which precipitated the escalation of this conflict.”

Cuba had spoken in Russia’s defense on Tuesday, with Ambassador Pedro Luis Cuesta blaming the crisis on what he said is the U.S. determination to keep expanding NATO toward Russia’s borders and on the delivery of modern weapons to Ukraine, ignoring Russia’s concerns for its own security. He told the assembly the resolution “suffers from lack of balance” and doesn’t begin to address the concerns of both parties, or “the responsibility of those who took aggressive actions which precipitated the escalation of this conflict.”

The resolution proposed by the US and Albania sought to declare that Russia has committed acts of aggression against Ukraine and the situation is a breach of international peace and security. It had also demanded that Russia immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine and completely withdraw its military forces from within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders.

The resolution proposed by the US and Albania sought to declare that Russia has committed acts of aggression against Ukraine and the situation is a breach of international peace and security. It had also demanded that Russia immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine and completely withdraw its military forces from within Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders. India was courted by both the US and Russia given the symbolic nature of the vote and the West’s desire to isolate the US. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday. And US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to press the case for voting for the resolution.

India was courted by both the US and Russia given the symbolic nature of the vote and the West’s desire to isolate the US. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke to Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday. And US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to press the case for voting for the resolution.

The 95-year-old said in a written message to the nation: “I would like to express my thanks to you all for your support. I remain eternally grateful for, and humbled by, the loyalty and affection that you continue to give me.”

The 95-year-old said in a written message to the nation: “I would like to express my thanks to you all for your support. I remain eternally grateful for, and humbled by, the loyalty and affection that you continue to give me.”

Lee Choon Geun, a missile expert and honorary research fellow at South Korea’s Science and Technology Policy Institute, said he thinks the photos were taken from space — especially when the missile was soaring to its apogee, though he cannot independently prove there was no adjustment on the images. While it’s rare to place a camera on a weapon, Lee said North Korea likely wanted to demonstrate its technological advancement to both foreign and domestic audiences.

Lee Choon Geun, a missile expert and honorary research fellow at South Korea’s Science and Technology Policy Institute, said he thinks the photos were taken from space — especially when the missile was soaring to its apogee, though he cannot independently prove there was no adjustment on the images. While it’s rare to place a camera on a weapon, Lee said North Korea likely wanted to demonstrate its technological advancement to both foreign and domestic audiences.

Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said up to 8,500 U.S. service members were put on heightened alert for deployment to bolster NATO allies’ eastern defenses should Russia invade. The forces would not be sent to Ukraine, which is not a NATO member, nor take part in any combat roles, Kirby said, but rather serve as reinforcements in places like Poland or Romania to reassure U.S. allies and deter Russian aggression. If activated, the troops would be part of the

Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said up to 8,500 U.S. service members were put on heightened alert for deployment to bolster NATO allies’ eastern defenses should Russia invade. The forces would not be sent to Ukraine, which is not a NATO member, nor take part in any combat roles, Kirby said, but rather serve as reinforcements in places like Poland or Romania to reassure U.S. allies and deter Russian aggression. If activated, the troops would be part of the  Putin denies Russia has any intention to attack Ukraine but he has made clear that he considers NATO military support for neighboring countries a growing threat. Last month, the Russian Foreign Ministry published two lengthy draft treaties that listed what Moscow wants from the U.S. and its allies. They call for an end to NATO’s eastward expansion, including a pledge that Ukraine will not be permitted to join NATO, as well as to the U.S. military’s ties with Ukraine and other former Soviet nations, all of which have been dismissed as “non-starters” by the U.S.

Putin denies Russia has any intention to attack Ukraine but he has made clear that he considers NATO military support for neighboring countries a growing threat. Last month, the Russian Foreign Ministry published two lengthy draft treaties that listed what Moscow wants from the U.S. and its allies. They call for an end to NATO’s eastward expansion, including a pledge that Ukraine will not be permitted to join NATO, as well as to the U.S. military’s ties with Ukraine and other former Soviet nations, all of which have been dismissed as “non-starters” by the U.S.

Greater domestic oppression synced with the invasion of Ukraine and further augmented the widespread sense that Russia, already the world’s largest country, deserves territory far beyond its gargantuan reach. This sense of fluid borders ranges from the far-right fantasies about an Eurasian Empire from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, to the more common “Russo-sphere.” In Russia’s case the term “sphere of influence” doesn’t only denote something hard and defined, which can be hammered out with other “great powers” in some grand new geopolitical deal, but something that swells and swings with the pistons of suppressed resentment and emotional dynamics.

Greater domestic oppression synced with the invasion of Ukraine and further augmented the widespread sense that Russia, already the world’s largest country, deserves territory far beyond its gargantuan reach. This sense of fluid borders ranges from the far-right fantasies about an Eurasian Empire from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, to the more common “Russo-sphere.” In Russia’s case the term “sphere of influence” doesn’t only denote something hard and defined, which can be hammered out with other “great powers” in some grand new geopolitical deal, but something that swells and swings with the pistons of suppressed resentment and emotional dynamics.

Although India embraced globalization at the turn of the 1990s, there was little domestic support for liberalizing trade. Opposing free trade agreements united the left and the right; even more powerful was the resistance from an Indian capitalist class reluctant to open its captive market for foreign producers.

Although India embraced globalization at the turn of the 1990s, there was little domestic support for liberalizing trade. Opposing free trade agreements united the left and the right; even more powerful was the resistance from an Indian capitalist class reluctant to open its captive market for foreign producers.

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, has

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, has

Pope Francis’ reform efforts at the Vatican and in the Catholic Church have been met with both enthusiasm and criticism. In March,

Pope Francis’ reform efforts at the Vatican and in the Catholic Church have been met with both enthusiasm and criticism. In March,

Evolution of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws Offences relating to religion in Pakistan were introduced in the colonial era in British India – which included the territory that is now Pakistan – to prevent and curb religious violence between Hindus and Muslims. Under the military government of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988), who set the process of Islamization in Pakistan, additional laws were introduced against blasphemy that were specific to Islam.

Evolution of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws Offences relating to religion in Pakistan were introduced in the colonial era in British India – which included the territory that is now Pakistan – to prevent and curb religious violence between Hindus and Muslims. Under the military government of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988), who set the process of Islamization in Pakistan, additional laws were introduced against blasphemy that were specific to Islam.

Early on the morning of Aug. 15, Karzai said, he waited to draw up the list. The capital was fidgety, on edge. Rumors were swirling about a Taliban takeover. Karzai called Doha. He was told the Taliban would not enter the city.

Early on the morning of Aug. 15, Karzai said, he waited to draw up the list. The capital was fidgety, on edge. Rumors were swirling about a Taliban takeover. Karzai called Doha. He was told the Taliban would not enter the city.

This was the second time in weeks that India went against the tide to block a climate change-related proposal that it did not agree with. At the annual climate change conference in Glasgow last month, India had forced a last-minute amendment in the final draft agreement to ensure that a provision calling for “phase-out” of coal was changed to “phase-down”.

This was the second time in weeks that India went against the tide to block a climate change-related proposal that it did not agree with. At the annual climate change conference in Glasgow last month, India had forced a last-minute amendment in the final draft agreement to ensure that a provision calling for “phase-out” of coal was changed to “phase-down”.

Russia has started delivering the S-400 Triumf surface-to-air missile system to India, the director of the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation (FSMTC) Dmitry Shugaev has said. The S-400 Triumf air defense missile system will give a major boost to India’s capabilities to take out enemy fighter aircraft and cruise missiles at long range. News agency ANI reported citing people familiar…

Russia has started delivering the S-400 Triumf surface-to-air missile system to India, the director of the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation (FSMTC) Dmitry Shugaev has said. The S-400 Triumf air defense missile system will give a major boost to India’s capabilities to take out enemy fighter aircraft and cruise missiles at long range. News agency ANI reported citing people familiar…

Such a discussion has never been more vital. The systems in place today once represented a clear improvement on prior regimes—monarchies, theocracies, and other tyrannies—but it may be a mistake to call them adherents of democracy at all. The word roughly translates from its original Greek as “people’s power.” But the people writ large doesn’t hold power in these systems. Elites do. Consider that in the United States, according to a

Such a discussion has never been more vital. The systems in place today once represented a clear improvement on prior regimes—monarchies, theocracies, and other tyrannies—but it may be a mistake to call them adherents of democracy at all. The word roughly translates from its original Greek as “people’s power.” But the people writ large doesn’t hold power in these systems. Elites do. Consider that in the United States, according to a

The diplomatic boycott is an escalation of President Joe Biden’s criticism of China’s treatment of its Uyghur citizens in a pattern of abuses that a

The diplomatic boycott is an escalation of President Joe Biden’s criticism of China’s treatment of its Uyghur citizens in a pattern of abuses that a

He even warned “It is time to go into emergency mode — or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero.” At the same time, Secretary-General’s rather confusing, ill-composed comment in his remarks at the conclusion of COP 26 that “We are still knocking on the door of climate catastrophe” left many wondering what he was trying to convey.

He even warned “It is time to go into emergency mode — or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero.” At the same time, Secretary-General’s rather confusing, ill-composed comment in his remarks at the conclusion of COP 26 that “We are still knocking on the door of climate catastrophe” left many wondering what he was trying to convey.

“The ultimate goal of the total elimination of nuclear weapons is both a challenge and a moral and humanitarian imperative,” Cardinal Parolin said. The Catholic Church has pressed for disarmament for decades.

“The ultimate goal of the total elimination of nuclear weapons is both a challenge and a moral and humanitarian imperative,” Cardinal Parolin said. The Catholic Church has pressed for disarmament for decades.

Senior journalist and former chairman of Pakistan Electronic Media Authority (PEMRA), Absar Alam was shot near his home in April 2021 but survived. Absar Alam has been critical of the country’s powerful military establishment. In a video message soon after the shooting, Alam said he had been hit in the ribs by a bullet and that he did not know the gunman. “I will not lose hope, and I am not going to be deterred by such acts,” Mr. Alam said in the video as he was being transported to a nearby hospital. “This is my message to the people who got me shot.”

Senior journalist and former chairman of Pakistan Electronic Media Authority (PEMRA), Absar Alam was shot near his home in April 2021 but survived. Absar Alam has been critical of the country’s powerful military establishment. In a video message soon after the shooting, Alam said he had been hit in the ribs by a bullet and that he did not know the gunman. “I will not lose hope, and I am not going to be deterred by such acts,” Mr. Alam said in the video as he was being transported to a nearby hospital. “This is my message to the people who got me shot.”

This amendment reportedly came as a result of consultations among India, China, the UK and the US. The phrase “phase down” figures in the US-China Joint Declaration on Climate Change, announced on November 10. As the largest producer and consumer of coal and coal-based thermal power, it is understandable that China would prefer a gradual reduction rather than total elimination. India may have had similar concerns. However, it was inept diplomacy for India to move the amendment and carry the can rather than let the Chinese bell the cat. The stigma will stick and was unnecessary.

This amendment reportedly came as a result of consultations among India, China, the UK and the US. The phrase “phase down” figures in the US-China Joint Declaration on Climate Change, announced on November 10. As the largest producer and consumer of coal and coal-based thermal power, it is understandable that China would prefer a gradual reduction rather than total elimination. India may have had similar concerns. However, it was inept diplomacy for India to move the amendment and carry the can rather than let the Chinese bell the cat. The stigma will stick and was unnecessary.

The 44th U.S. president commended the private sector’s push to set net-zero emissions targets and also touted emissions reductions targets set in the U.K. and the European Union, while pointing out the absence of Chinese and Russian leaders from the summit.

The 44th U.S. president commended the private sector’s push to set net-zero emissions targets and also touted emissions reductions targets set in the U.K. and the European Union, while pointing out the absence of Chinese and Russian leaders from the summit.

Despite the fact that the

Despite the fact that the According to analysts, Methane emission reductions from oil and gas production are the low-hanging fruit of the climate crisis: easy to fix with existing technology, and easy to track. Methane is the principal component of the natural gas used for cooking, heating and energy generation.

According to analysts, Methane emission reductions from oil and gas production are the low-hanging fruit of the climate crisis: easy to fix with existing technology, and easy to track. Methane is the principal component of the natural gas used for cooking, heating and energy generation.

Anand, 54, will replace long-time defense minister Indian-origin Harjit Sajjan, whose handling of the military sexual misconduct crisis has been under criticism.

Anand, 54, will replace long-time defense minister Indian-origin Harjit Sajjan, whose handling of the military sexual misconduct crisis has been under criticism.

With temperatures rising and extreme weather occurring across the globe, all eyes at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference will be on China, the leading producer of greenhouse gases, and the United States, the largest emitter both historically and on a per capita basis.

With temperatures rising and extreme weather occurring across the globe, all eyes at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference will be on China, the leading producer of greenhouse gases, and the United States, the largest emitter both historically and on a per capita basis.

In Washington, where policymakers have been grappling with the fallout from the sudden Taliban takeover of Kabul in August and the scrambled evacuation that followed, the focus has shifted to identifying the mistakes made in the war in Afghanistan. Washington is taking a hard look at where things went wrong — and Pakistan, given its long history with the Taliban, is part of that equation.

In Washington, where policymakers have been grappling with the fallout from the sudden Taliban takeover of Kabul in August and the scrambled evacuation that followed, the focus has shifted to identifying the mistakes made in the war in Afghanistan. Washington is taking a hard look at where things went wrong — and Pakistan, given its long history with the Taliban, is part of that equation.

According to the Update issued ahead of the Bank’s annual meeting next week, India’ gross domestic product (GDP) — which shrank by 7.3 per cent (that is, a minus 7.3 per cent) under the onslaught of the pandemic last fiscal year — is expected to record the 8.3 per cent growth this fiscal year, which will moderate to 7.5 per cent next year and 6.5 per cent in 2023-24. Of the major economies, China is ahead with its economy expected to grow by 8.5 per cent during the current calendar year after the Bank revised it upwards from the 8.1 per cent projection in April.

According to the Update issued ahead of the Bank’s annual meeting next week, India’ gross domestic product (GDP) — which shrank by 7.3 per cent (that is, a minus 7.3 per cent) under the onslaught of the pandemic last fiscal year — is expected to record the 8.3 per cent growth this fiscal year, which will moderate to 7.5 per cent next year and 6.5 per cent in 2023-24. Of the major economies, China is ahead with its economy expected to grow by 8.5 per cent during the current calendar year after the Bank revised it upwards from the 8.1 per cent projection in April.

“At the same time, they are representatives of all journalists who stand up for this ideal in a world in which democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions,” she added. “Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda.” Muratov dedicated his award to six contributors to his Novaya Gazeta newspaper who had been murdered for their work exposing human rights violations and corruption.

“At the same time, they are representatives of all journalists who stand up for this ideal in a world in which democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions,” she added. “Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda.” Muratov dedicated his award to six contributors to his Novaya Gazeta newspaper who had been murdered for their work exposing human rights violations and corruption.

“In recognizing Maria, the Nobel committee now sees that anti-democratic leaders who want to muzzle press freedom don’t just use the old tools – arrests, detention, death threats, closing media outlets,” said Pensky. “Now they depend on social media, too. Maria’s courageous work in the Philippines calls out strongman Rodrigo Duterte and Facebook for using fake news, troll armies, and online harassment, combined with “old school” government intimidation, in a new, toxic mix. Maria’s award is for letting the world know how this actually works in her own country, and warning us that we all have to face it if we want press freedom of our own.”

“In recognizing Maria, the Nobel committee now sees that anti-democratic leaders who want to muzzle press freedom don’t just use the old tools – arrests, detention, death threats, closing media outlets,” said Pensky. “Now they depend on social media, too. Maria’s courageous work in the Philippines calls out strongman Rodrigo Duterte and Facebook for using fake news, troll armies, and online harassment, combined with “old school” government intimidation, in a new, toxic mix. Maria’s award is for letting the world know how this actually works in her own country, and warning us that we all have to face it if we want press freedom of our own.”

“These are secretive, confidential documents from offshore tax havens and offshore specialists who work to help rich, powerful and sometimes criminal individuals create shell companies or trusts in a way that often helps either obscure assets or in some cases even help avoid paying taxes,” senior ICIJ reporter Will Fitzgibbon

“These are secretive, confidential documents from offshore tax havens and offshore specialists who work to help rich, powerful and sometimes criminal individuals create shell companies or trusts in a way that often helps either obscure assets or in some cases even help avoid paying taxes,” senior ICIJ reporter Will Fitzgibbon  In February 2020, following a dispute with three Chinese state-controlled banks, Anil Ambani told a London court that his net worth was zero. Records in the Pandora Papers investigated by The Indian Express reveal that the chairman of Reliance ADA Group and his representatives

In February 2020, following a dispute with three Chinese state-controlled banks, Anil Ambani told a London court that his net worth was zero. Records in the Pandora Papers investigated by The Indian Express reveal that the chairman of Reliance ADA Group and his representatives

Kishida was installed as LDP leader after a deal among party power-brokers—despite what many political observers say is his lack of personal appeal and much broader public support for Kono. Kishida was supported by one of the LDP’s largest factions, but only led Kono by one vote in the first round of party voting. Yoshikazu Kato, a director of a Tokyo-based research and consulting firm Trans-Pacific Group (TPG), believes Kishida’s team was able to secure more votes with help from supporters of ultraconservative candidate Sanae Takaichi—who was vying to become Japan’s first female prime minister.

Kishida was installed as LDP leader after a deal among party power-brokers—despite what many political observers say is his lack of personal appeal and much broader public support for Kono. Kishida was supported by one of the LDP’s largest factions, but only led Kono by one vote in the first round of party voting. Yoshikazu Kato, a director of a Tokyo-based research and consulting firm Trans-Pacific Group (TPG), believes Kishida’s team was able to secure more votes with help from supporters of ultraconservative candidate Sanae Takaichi—who was vying to become Japan’s first female prime minister.

In 1990, a heady sense of opportunity in both West and East Germany created the public support that Helmut Kohl needed to take on one of the most ambitious and complex global governing challenges since the end of World War II. Over the Merkel era of the past 16 years, by contrast, Germans (and Europeans generally) have needed a thoughtful, flexible problem-solver to guide them through a debt emergency, a surge of migrants from the Middle East, and the deadliest global pandemic in a century. In the process, Angela Merkel helped save the European Union. That’s an accomplishment that deserves lasting respect.

In 1990, a heady sense of opportunity in both West and East Germany created the public support that Helmut Kohl needed to take on one of the most ambitious and complex global governing challenges since the end of World War II. Over the Merkel era of the past 16 years, by contrast, Germans (and Europeans generally) have needed a thoughtful, flexible problem-solver to guide them through a debt emergency, a surge of migrants from the Middle East, and the deadliest global pandemic in a century. In the process, Angela Merkel helped save the European Union. That’s an accomplishment that deserves lasting respect.

Delhi’s

Delhi’s

In November 2017, India, Japan, the U.S. and Australia gave shape to the long-pending proposal of setting up

In November 2017, India, Japan, the U.S. and Australia gave shape to the long-pending proposal of setting up

If that did happen, the Taliban would have earned the dubious distinction of being the only government in the world to hang two presidents. But mercifully, it did not. Ghani, however, denied that he had bolted from the presidential palace lugging several suitcases with millions of dollars pilfered from the country’s treasury. Meanwhile, when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan during 1996-2001, only three countries recognized its legitimacy: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and UAE.

If that did happen, the Taliban would have earned the dubious distinction of being the only government in the world to hang two presidents. But mercifully, it did not. Ghani, however, denied that he had bolted from the presidential palace lugging several suitcases with millions of dollars pilfered from the country’s treasury. Meanwhile, when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan during 1996-2001, only three countries recognized its legitimacy: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and UAE.

SPD leader Olaf Scholz said he had a clear mandate to form a government, while his conservative rival Armin Laschet remains determined to fight on. The Social Democrats’ candidate Olaf Scholz, the outgoing vice chancellor and finance minister who pulled his party out of a years-long slump, said the outcome was “a very clear mandate to ensure now that we put together a good, pragmatic government for Germany.”

SPD leader Olaf Scholz said he had a clear mandate to form a government, while his conservative rival Armin Laschet remains determined to fight on. The Social Democrats’ candidate Olaf Scholz, the outgoing vice chancellor and finance minister who pulled his party out of a years-long slump, said the outcome was “a very clear mandate to ensure now that we put together a good, pragmatic government for Germany.”

Guterres said the world’s two major economic powers should be cooperating on climate and negotiating more robustly on trade and technology even given persisting political fissures about

Guterres said the world’s two major economic powers should be cooperating on climate and negotiating more robustly on trade and technology even given persisting political fissures about

So on Monday, Guterres and United Kingdom Prime Minister Boris Johnson are hosting a closed-door session with 35 to 40 world leaders to get countries to do more leading up to the huge climate negotiations in Scotland in six weeks. Those negotiations in the fall are designed to be the next step after the