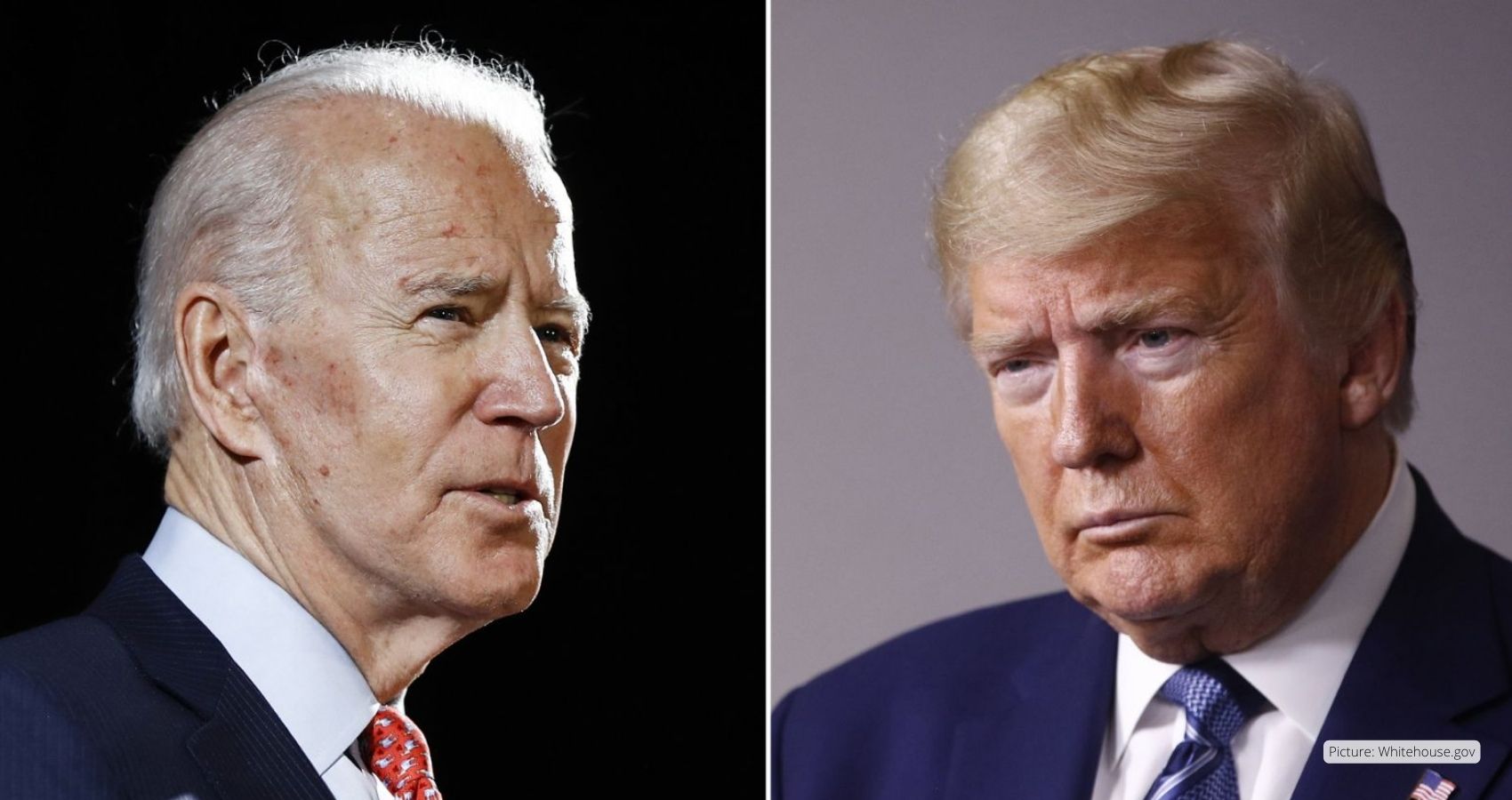

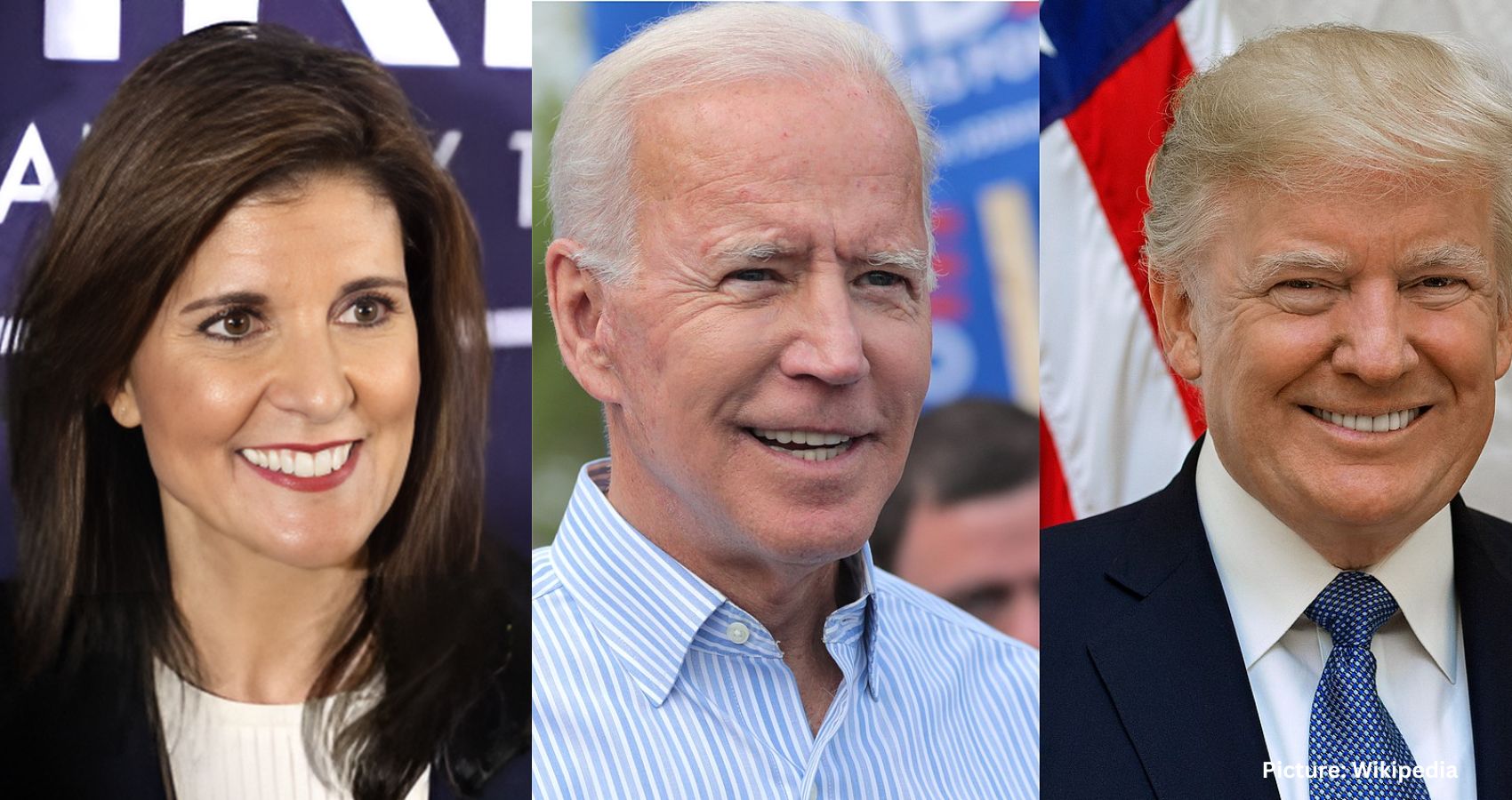

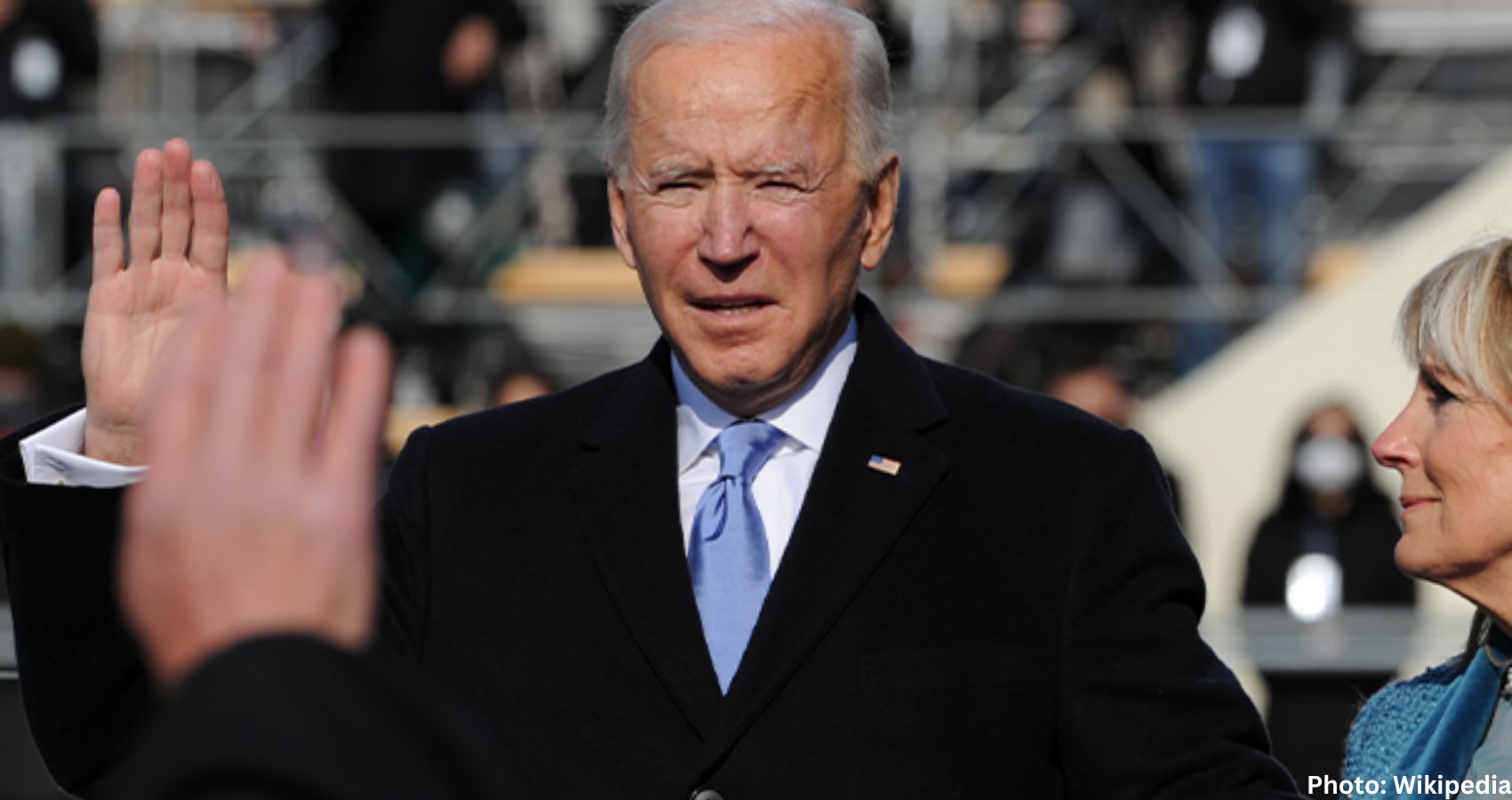

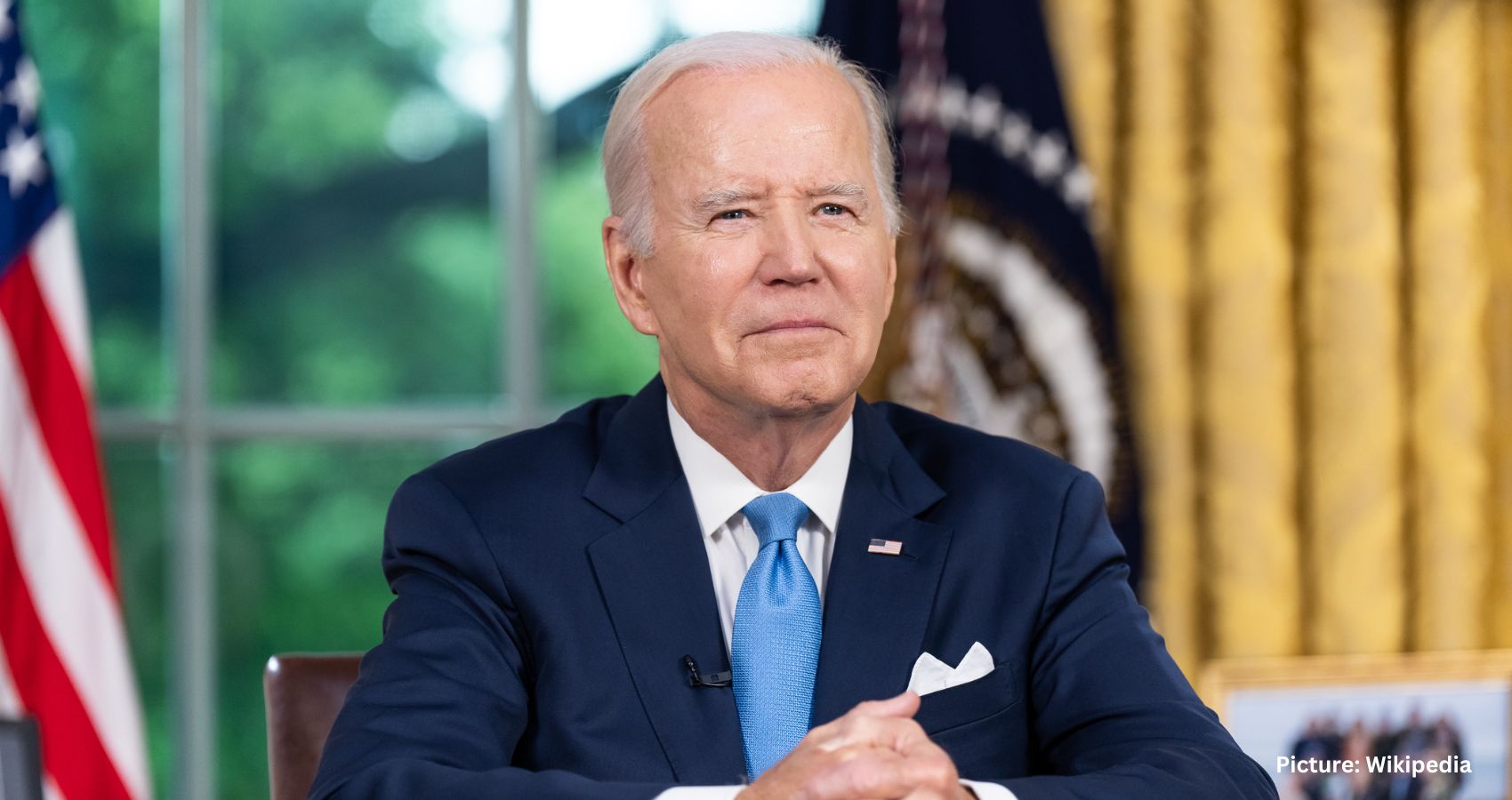

On a pivotal day in Washington, President Joe Biden held onto the Democratic nomination, though concerns about his decision to stay in the race were starkly highlighted. One of his party’s senators warned on CNN that Donald Trump could win in a “landslide,” underlining the risks involved in Biden’s refusal to step aside.

Biden’s determination has left Democrats increasingly worried that the president could jeopardize not only the White House but also their chances of retaking the House or retaining the Senate—challenges already seen as uphill battles.

The White House managed to quell rebellions in emotional meetings with Senate and House Democrats on Tuesday. However, even some of Biden’s supporters expressed doubts about his strategies and his ability to run a successful campaign. Uncertainty about Biden’s future grew on Wednesday with comments from former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and actor George Clooney, who urged Biden to step aside.

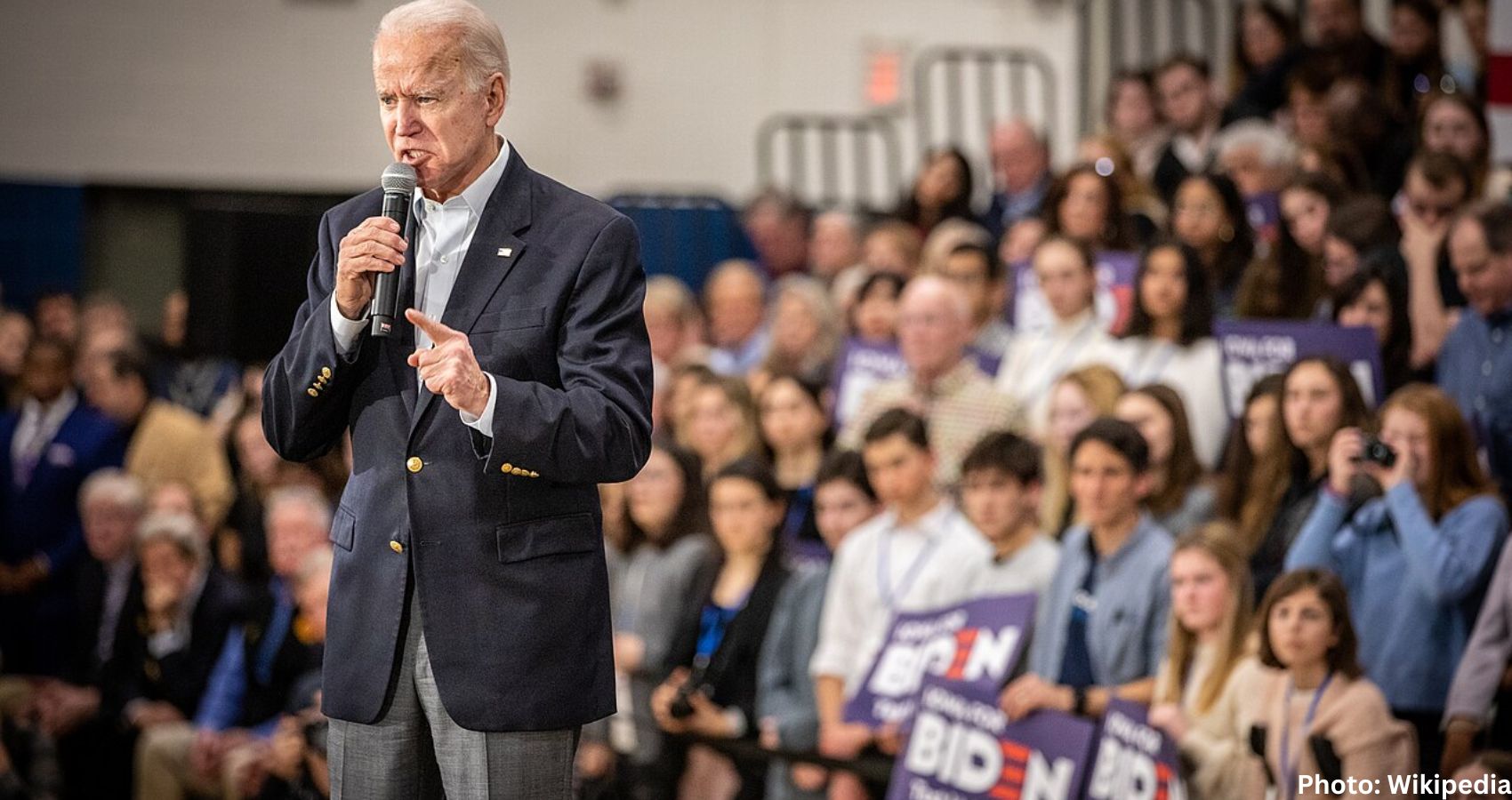

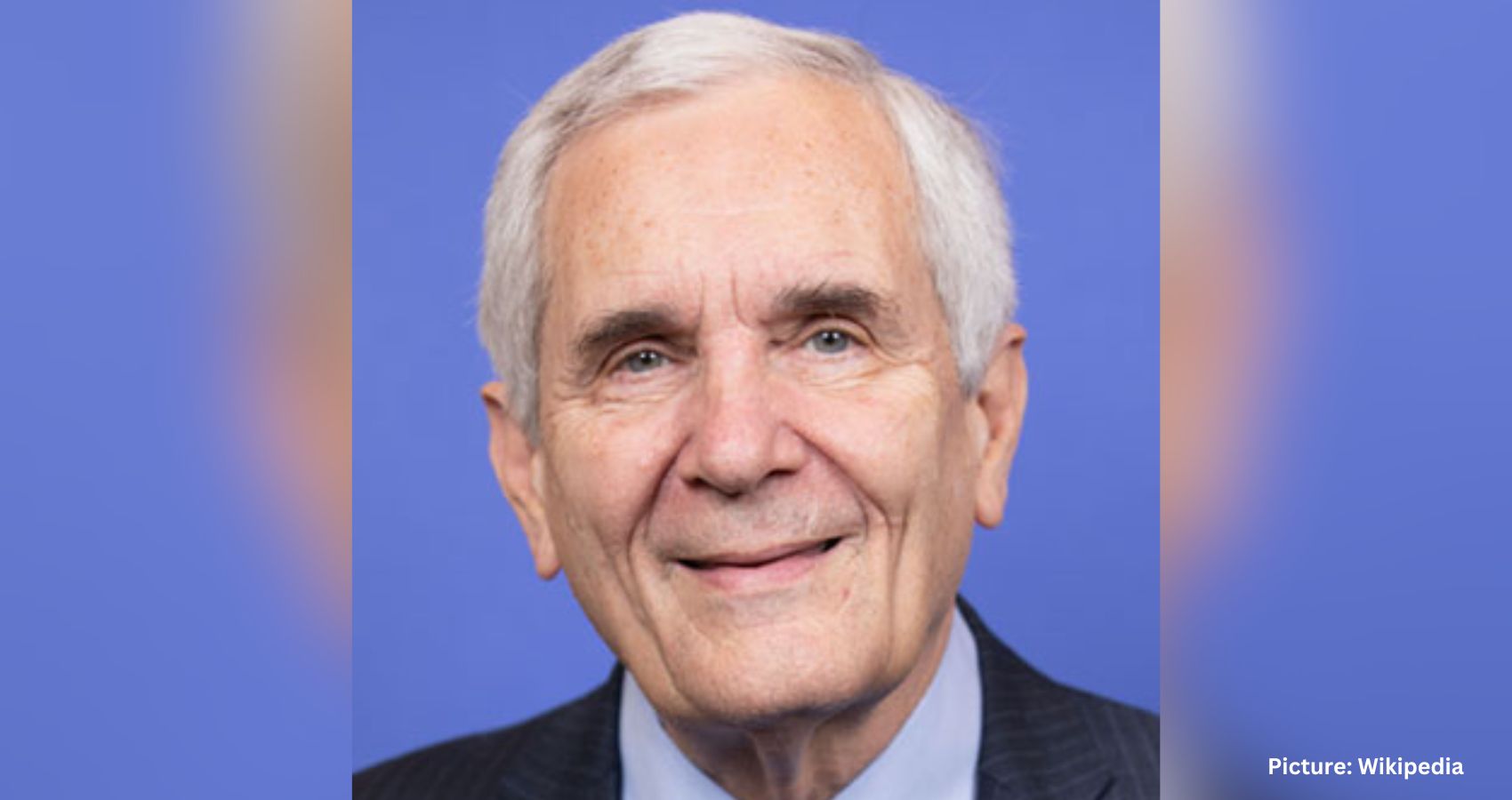

Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado was among three Democrats who privately expressed concerns about Biden’s chances of winning in November, sources told CNN’s Dana Bash. Bennet later publicly voiced his fears. “Donald Trump is on track, I think, to win this election and maybe win it by a landslide and take with him the Senate and the House,” Bennet said on CNN. “So for me, this isn’t a question about polling. It’s not a question about politics. It’s a moral question about the future of our country.”

“The White House, in the time since that disastrous debate, I think, has done nothing to really demonstrate that they have a plan to win this election,” he added.

While Bennet’s comments do not reflect the public stance of all Democratic senators, the debate and its aftermath have undeniably stirred deep concerns within the party.

Pelosi alluded to this anxiety during an MSNBC appearance, suggesting that Biden’s place on the Democratic ticket was still in question despite his firm stance. “It’s up to the president to decide if he is going to run. We’re all encouraging him to make that decision because time is running short,” she said. “I want him to do whatever he decides to do and that’s the way it is.”

In a striking op-ed in The New York Times, Clooney criticized Biden after attending a fundraiser with him last month. “It’s devastating to say it, but the Joe Biden I was with three weeks ago at the fundraiser was not the Joe ‘big F-ing deal’ Biden of 2010. He wasn’t even the Joe Biden of 2020. He was the same man we all witnessed at the debate,” Clooney wrote. “We are not going to win in November with this president,” he warned, noting that lawmakers he spoke with privately shared this view.

The last two weeks have significantly weakened Biden’s standing within a party already lukewarm about his campaign. His recent missteps threaten to narrow an already fragile path to reelection against a revitalized Trump, who held a fiery rally in Florida on Tuesday, nine days before he’s set to accept the Republican nomination.

Deep unease over Biden’s prospects permeated through Democratic senators and representatives in Washington on Tuesday, with venting sessions taking place behind closed doors. Despite growing calls for him to step aside, Biden managed to maintain his grip on the nomination with support from Senate and House leaders, albeit lukewarm.

In a letter to lawmakers on Monday, Biden reaffirmed his commitment to the race: “I am firmly committed to staying in this race.” This, coupled with the primary voters’ decisions, left his critics with little room to maneuver. Pelosi, however, hinted that the matter was still open. “Just hold off, whatever you’re thinking, either tell somebody privately but you don’t have to put that out on the table until we see how we go this week,” she advised Democrats. After her comments circulated widely, a spokesperson clarified that Pelosi “fully supports whatever President Biden decides to do.”

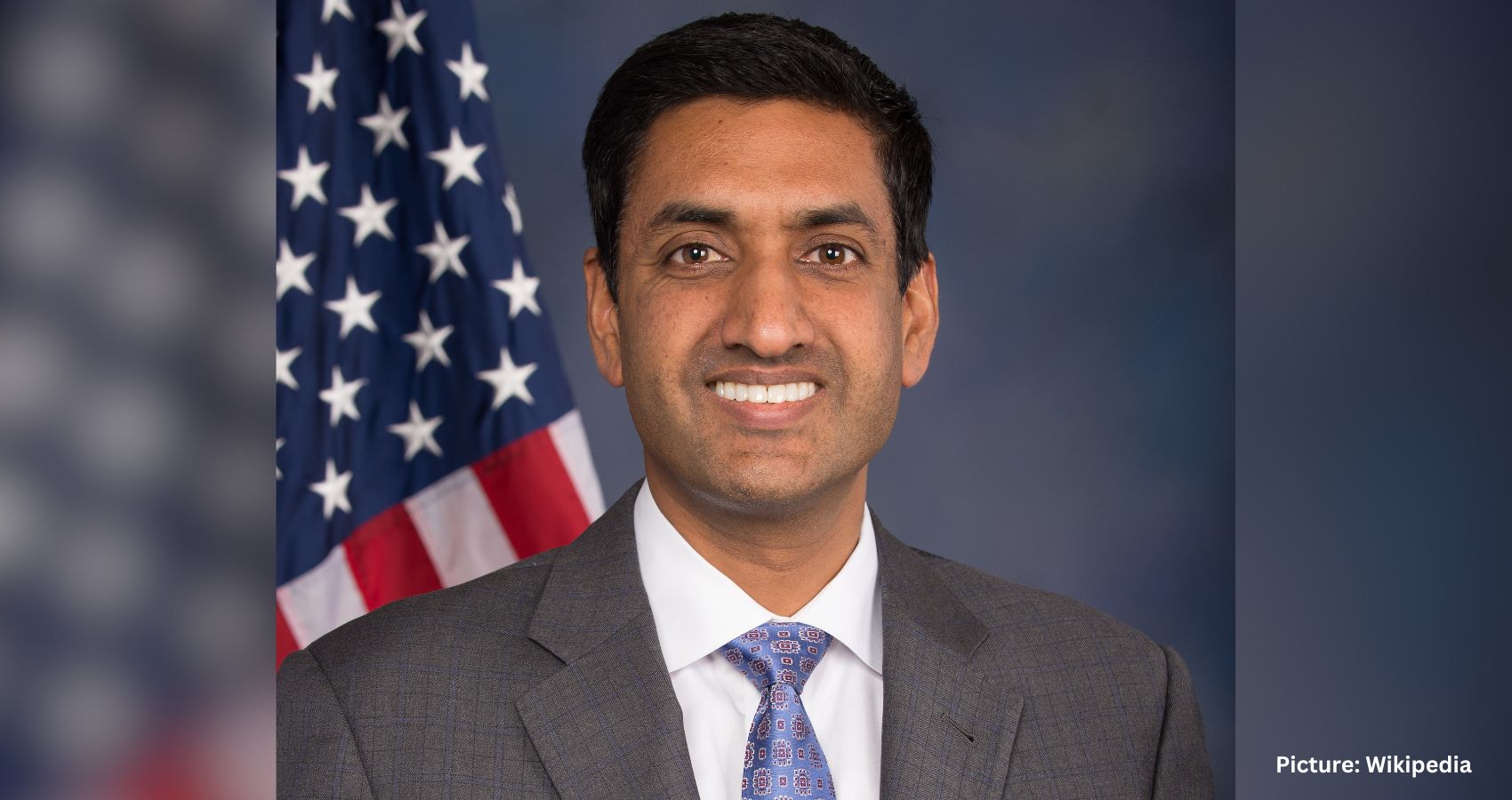

Rep. Ritchie Torres provided a stark warning to CNN about the potential impact on other races if Biden continues his bid for reelection. “If we are going on a political suicide mission, then we should at least be honest about it,” he said, adding, “There must be a serious reckoning with the down-ballot effect of whomever we nominate.”

Biden faces another critical test on Thursday with a solo press conference at the end of the NATO summit. Any mistakes or confusion could further undermine Democratic support.

The crisis surrounding Biden’s campaign reflects the broader turmoil within the Democratic Party, which is grappling with concerns about his viability, strength, and mental capacity less than four months from Election Day. There is scant evidence that Biden is ready to engage in intensive campaign activities, which many Democrats believe are essential for a successful run. Some Democrats doubt his chances of winning in November, while the urgency of the situation is magnified by Trump’s strong political position.

Tuesday was seen as a crucial day for Biden, as it marked the first time lawmakers had gathered en masse since the debate and the July Fourth recess. Despite an increase in calls for him to step aside, Biden managed to stabilize his campaign’s crisis.

“We do want to turn the page. We want to get to the other side of this,” White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters, though the president’s political challenges as the oldest-ever president remain significant.

Biden delivered one of his strongest recent public appearances at the NATO summit in Washington on Tuesday, even as the effects of aging were evident in his speech and movements. “Remember, the biggest cost and the greatest risk will be if Russia wins in Ukraine. We cannot let that happen,” he said, praising NATO as “the single greatest, most effective defense alliance in the history of the world.”

The summit was intended to highlight Biden’s leadership as a key figure in the West since World War II and to contrast him with Trump, who often criticized America’s European allies. Instead, it has become a test of Biden’s mental acuity.

White House officials told CNN’s Kayla Tausche that Biden’s speech went according to plan and hoped it would allow him to resume “business as usual.” However, every public appearance by the president now feels like an excruciating wait for potential gaffes, awkward moments, or freezes. His debate performance left an unflattering impression on 50 million viewers, and it’s a low bar for a president to deliver a short, scripted speech without issues.

The situation is unlikely to improve over the next four months due to the inherent challenges of Biden’s matchup with Trump and his decision to run for a term that would end when he is 86.

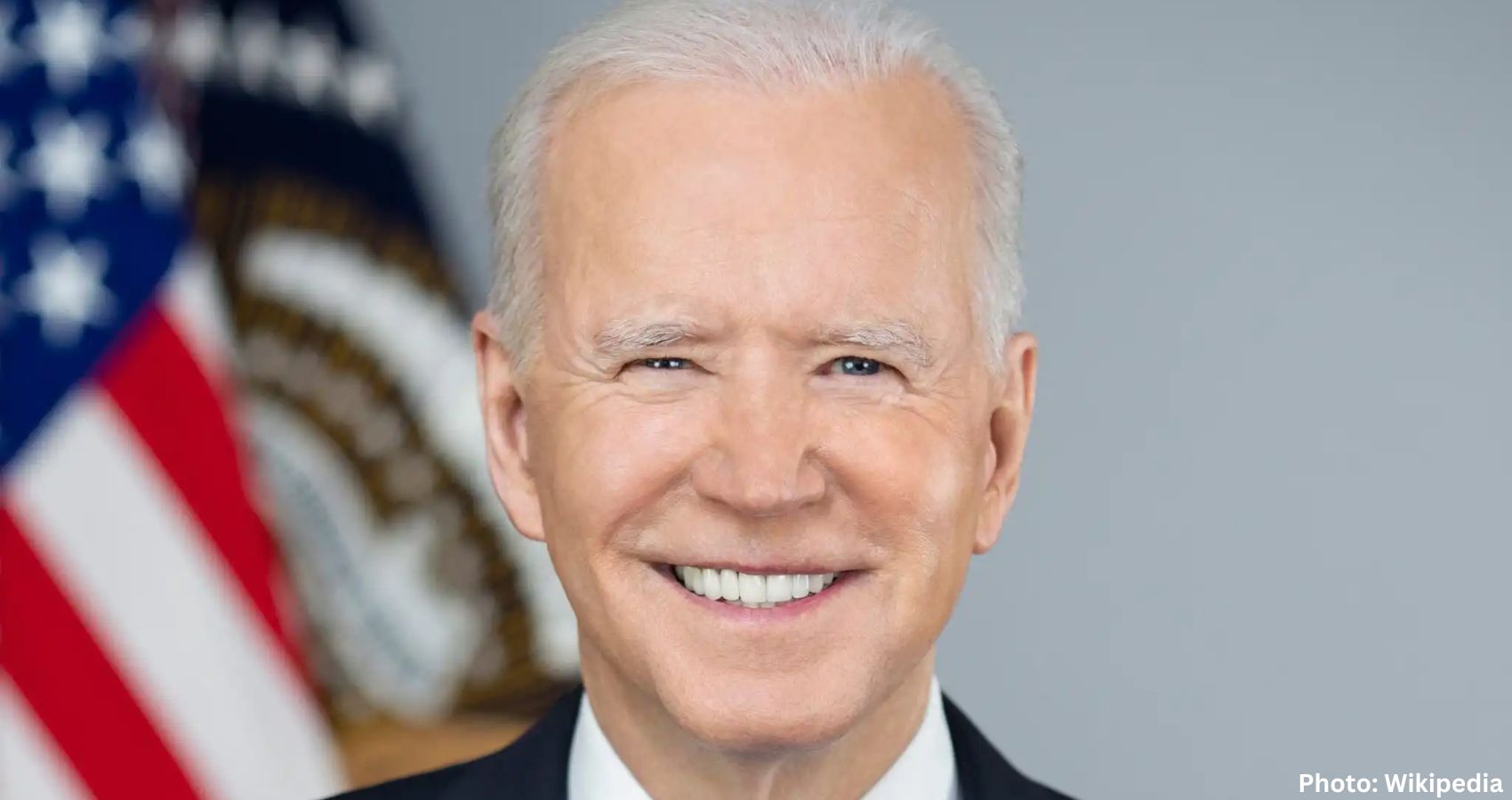

Nevertheless, it’s too early to count Biden out. Voters decide elections, not lawmakers or media commentary. Biden has repeatedly defied predictions of his political demise and has shown resilience despite personal and political setbacks. Trump, a convicted criminal, has a knack for alienating moderate, suburban, and swing voters with his extreme rhetoric and threats.

The Republican National Convention in Milwaukee next week, which will likely turn into a MAGA festival, is seen by the Biden camp as an opportunity to highlight the contrast with Trump, which Biden’s debate performance had temporarily obscured.

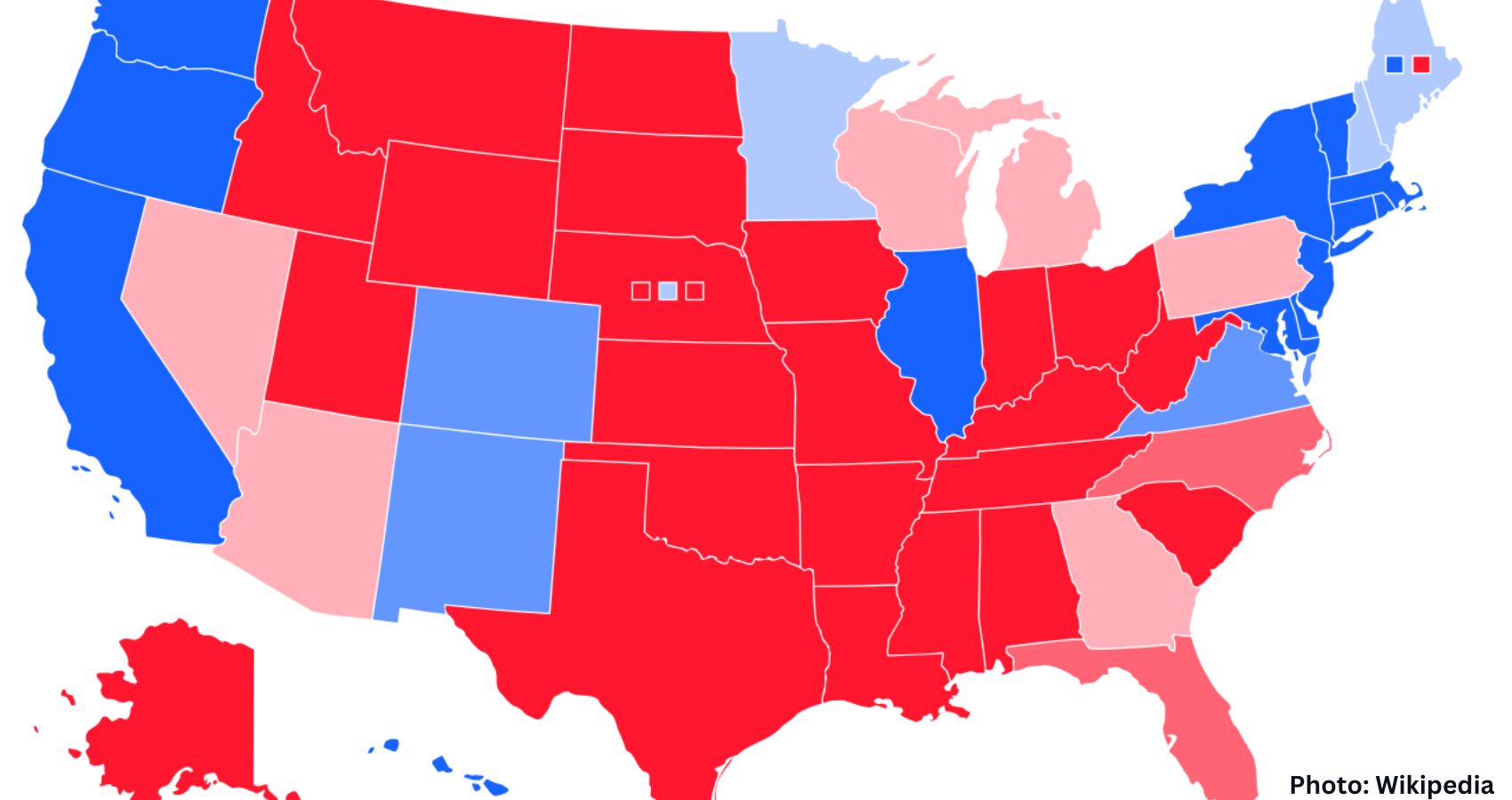

Most post-debate national polls suggest Biden lost a couple of points to Trump, making an already close race tighter. However, there is little quality polling in swing states since the debate. Biden was generally trailing Trump in many battlegrounds before the debate and needed to reset the race, but instead, he created negative momentum.

Biden’s failure to frame a sharp contrast with Trump on key issues like abortion, taxes, character, and Trump’s threat to democracy and US values has fueled Democratic despair.

This disappointment was evident as lawmakers entered their meetings on Tuesday, with many avoiding reporters afterward. A source told CNN’s Bash that Sens. Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Jon Tester of Montana joined Bennet in expressing doubts about Biden’s chances.

“It’s true that I said that,” Bennet told CNN. “Donald Trump is on track, I think, to win this election and maybe win it by a landslide and take with him the Senate and the House.”

Sen. Angus King, an independent from Maine who caucuses with Democrats, said senators believe Biden must engage in unscripted situations to address voters’ questions. Asked about the risks of Biden stumbling, King replied: “It seems to me that’s a risk they have to take. If he’s OK, it shouldn’t be a problem.”

Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman defended Biden. “We concluded that Joe Biden is old; we found out, and the polling came back that he’s old,” Fetterman told CNN. “But we also agreed that he’s our guy.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, asked about Biden, responded tersely, “I’m with Joe,” indicating his support.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler, who had privately doubted Biden’s candidacy, said he now supports him, though his decision seemed driven by the difficulty of replacing Biden rather than confidence in his strength. “I’m not resigned to it. He made very clear he’s going to run. He’s got an excellent record, one of the most excellent presidents of the last century. Trump would be an absolute disaster for democracy; so, I’m enthusiastically supporting Biden,” Nadler said.

The Congressional Black Caucus, a powerful House Democratic Caucus faction, has also bolstered Biden’s support. Many CBC members are in safe districts and may face less pressure than frontline Democrats critical of Biden’s debate performance. Texas Rep. Marc Veasey voiced concerns for vulnerable colleagues, criticizing Biden’s post-debate efforts. “Whatever I have seen so far hasn’t shown me that that’s going to be enough to get there. I just don’t think that dog is gonna hunt,” Veasey told CNN. “I think that he has a long way to go and I think there are stronger candidates that would be more likely to beat Trump at this point, but if he says that he is going to stay in, (then) he’s the nominee.”

Rep. Mikie Sherrill of New Jersey praised Biden’s presidency but became the seventh House Democrat to call for him to step aside. “Because I know President Biden cares deeply about the future of our country, I am asking that he declare that he won’t run for reelection and will help lead us through a process toward a new nominee.”

Some Democratic leaders sought to rally their members by attacking Trump. “Every single member of the House Democratic Caucus is clear-eyed about what the stakes of this election are,” said Rep. Pete Aguilar, the caucus chairman. “Donald Trump cannot be allowed near the Oval Office and his extremist allies must never be allowed to pass a national abortion ban or their dangerous Project 2025, which would erode our democracy and enable Trump’s worst impulses,” the California Democrat said. His forceful presentation underscored the missed opportunities Biden had in the debate.

In Las Vegas, Vice President Kamala Harris attacked Trump with the vigor of a former prosecutor. “I will say that someone who vilifies immigrants, who promotes xenophobia, someone who stokes hate should never again have the chance to stand behind a microphone and the seal of the President of the United States,” Harris said.

For Democrats who believe Harris would be a stronger nominee, her dynamic delivery highlighted an alternative path that Biden has closed off.

NAINA stands as the representing voice of the tens of thousands among the 4.7 million nurses in the healthcare arena. The primary goal of NAINA is to provide service to and bring all the nurses and nursing students of Indian origin under one umbrella. With twenty chapters across the nation, NAINA stands as the sole national organization of Indian nurses with thousands of nurses enjoying the benefits of its membership. In the mainstream, NAINA is closely associated with American Nurses Association, CGFNS International, National Coalition of Ethnic Minority Nurses Organization, and National Council of State Board of Nursing. As we witness Indian Americans all across the life spectrum in the country, the Indian American nurses have already established their presence in healthcare. You will Indian nurses at bedside, in outpatient clinics, nursing leadership, nursing education, hospital administration, university faculty, and research. They are ambitious; they uphold a vision of high-quality healthcare. They believe that higher education can equip them with advanced knowledge, critical thinking skills, upward career opportunities, professional respect, and healthcare progress.” Suja Thomas, the president of NAINA emphasized. Suja, a nursing administrator and an adjunct professor, is also in the governing team of CGFNS International. The leadership team of NAINA also represents nursing professionals with expertise from diverse fields.

NAINA stands as the representing voice of the tens of thousands among the 4.7 million nurses in the healthcare arena. The primary goal of NAINA is to provide service to and bring all the nurses and nursing students of Indian origin under one umbrella. With twenty chapters across the nation, NAINA stands as the sole national organization of Indian nurses with thousands of nurses enjoying the benefits of its membership. In the mainstream, NAINA is closely associated with American Nurses Association, CGFNS International, National Coalition of Ethnic Minority Nurses Organization, and National Council of State Board of Nursing. As we witness Indian Americans all across the life spectrum in the country, the Indian American nurses have already established their presence in healthcare. You will Indian nurses at bedside, in outpatient clinics, nursing leadership, nursing education, hospital administration, university faculty, and research. They are ambitious; they uphold a vision of high-quality healthcare. They believe that higher education can equip them with advanced knowledge, critical thinking skills, upward career opportunities, professional respect, and healthcare progress.” Suja Thomas, the president of NAINA emphasized. Suja, a nursing administrator and an adjunct professor, is also in the governing team of CGFNS International. The leadership team of NAINA also represents nursing professionals with expertise from diverse fields. same time and will bring out new research outcomes and evidence- based practice initiatives that could empower and embolden nurses with knowledge and skills to bring back to their home practices. Attendees of each session will get continuing education credits that could be used for maintaining their specialty certifications and help nurses to achieve promotional initiatives like Clinical Ladder. Tara Shajan, a nursing director at Health and Hospitals Corporation of New York who is the National Convenor and the treasure of NAINA pointed at the networking opportunities that NAINA conference provides to the attendees. “Besides the valuable continuing education credits, you get opportunities to network with bedside nurses from all specialties, scholars, nurse practitioners and educators from California to Main and Florida to Minnesota. You can inspire and get inspired!”

same time and will bring out new research outcomes and evidence- based practice initiatives that could empower and embolden nurses with knowledge and skills to bring back to their home practices. Attendees of each session will get continuing education credits that could be used for maintaining their specialty certifications and help nurses to achieve promotional initiatives like Clinical Ladder. Tara Shajan, a nursing director at Health and Hospitals Corporation of New York who is the National Convenor and the treasure of NAINA pointed at the networking opportunities that NAINA conference provides to the attendees. “Besides the valuable continuing education credits, you get opportunities to network with bedside nurses from all specialties, scholars, nurse practitioners and educators from California to Main and Florida to Minnesota. You can inspire and get inspired!” Integrating Research, and Technological Innovation for Enhancing Practice.” Mukul Bhakshi, Chief of Strategy and Governmental Affairs, will be another guest speaker. Dr. Debbie Hatmaker, Chief Nursing Officer of American Nurses Association, and Dr Kelly Foltz-Ramos, director of simulation & innovation and assistant professor at University at Buffalo School of Nursing will be the guest speakers on Saturday, the second day. Dr. Glenda B. Kelman, chair and professor of nursing at Russell Sage College Troy will do the keynote presentation on “Overcoming Imposter Syndrome in the Age of Technological Innovation in Nursing Practice.” The concurrent sessions will follow.

Integrating Research, and Technological Innovation for Enhancing Practice.” Mukul Bhakshi, Chief of Strategy and Governmental Affairs, will be another guest speaker. Dr. Debbie Hatmaker, Chief Nursing Officer of American Nurses Association, and Dr Kelly Foltz-Ramos, director of simulation & innovation and assistant professor at University at Buffalo School of Nursing will be the guest speakers on Saturday, the second day. Dr. Glenda B. Kelman, chair and professor of nursing at Russell Sage College Troy will do the keynote presentation on “Overcoming Imposter Syndrome in the Age of Technological Innovation in Nursing Practice.” The concurrent sessions will follow.

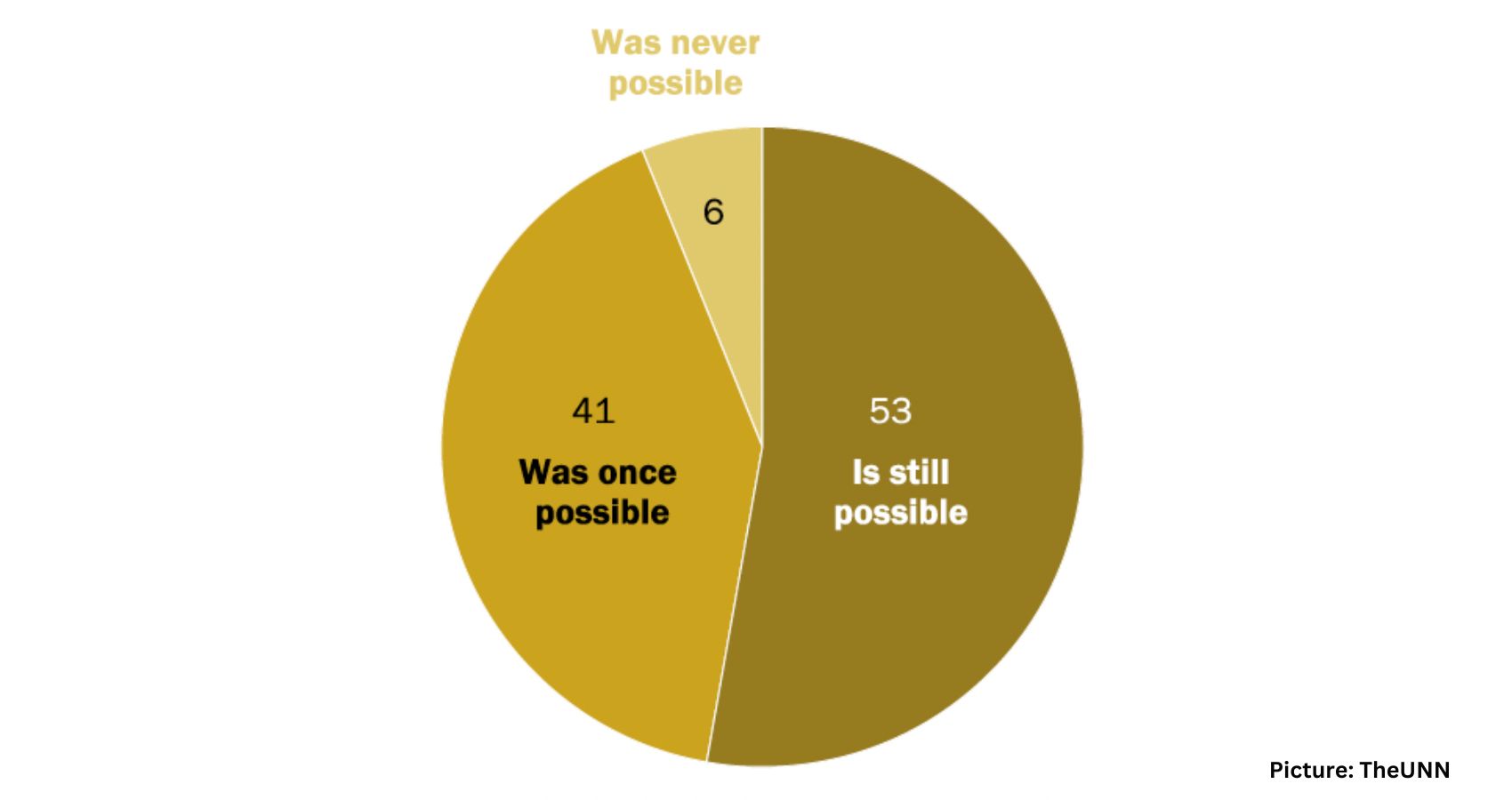

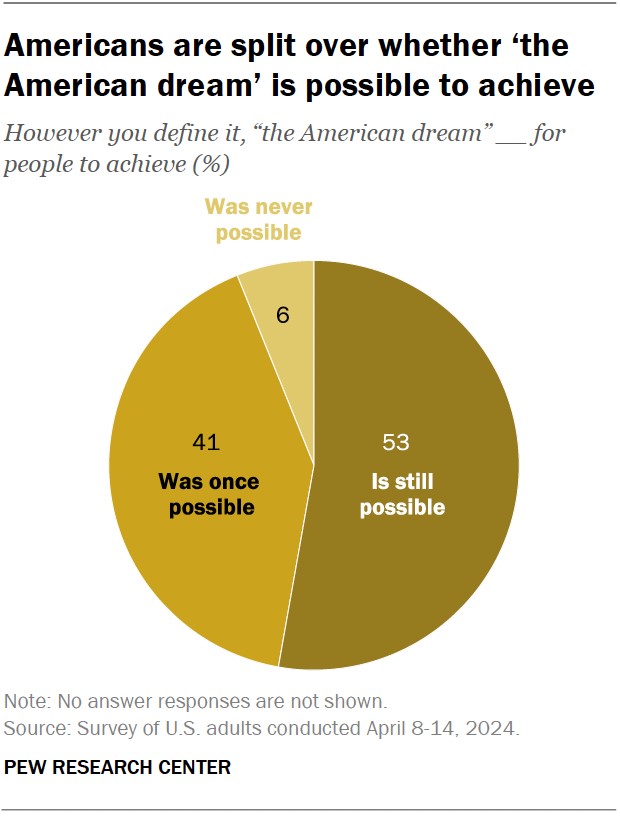

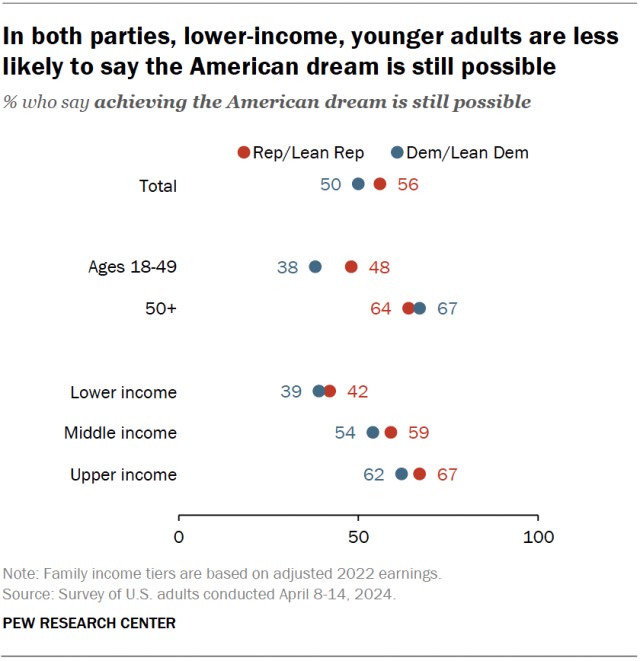

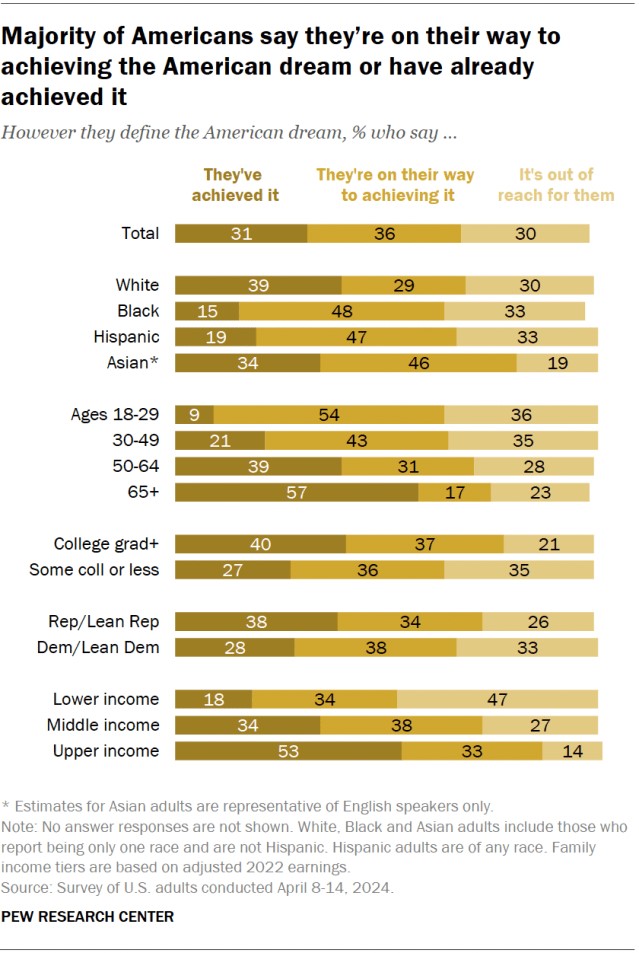

dream.

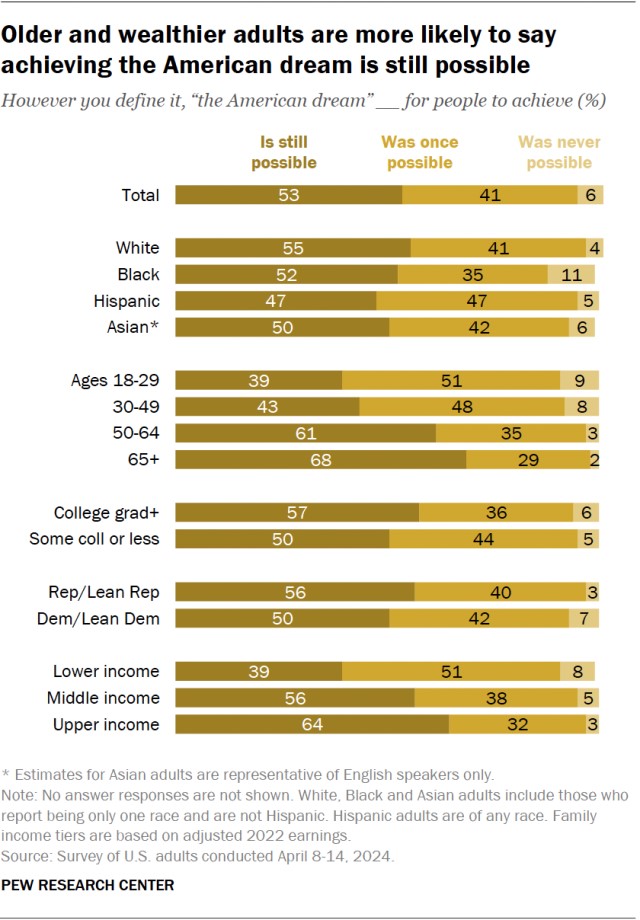

dream. Age and income differences in views of the American dream persist within each political party.

Age and income differences in views of the American dream persist within each political party.

This Press conference begun by singing American National Anthem by Mathy Pillai, a renowned singer and pledge of Allegiance by Rima.

This Press conference begun by singing American National Anthem by Mathy Pillai, a renowned singer and pledge of Allegiance by Rima. reasons, AARC announced its full support to President Trump to win Presidential elections on November 05, 2024.

reasons, AARC announced its full support to President Trump to win Presidential elections on November 05, 2024. Several Asian Indian American Republicans encouraged and appealed the community to come forward in support of President Donald J Trump’s candidacy.

Several Asian Indian American Republicans encouraged and appealed the community to come forward in support of President Donald J Trump’s candidacy.