In the last 2 decades, US poured money and resources into protecting the U.S. from another terrorist attack, even as the nature of that threat continuously evolved.

In the fall of 2001, Aaron Zebley was a 31-year-old FBI agent in New York. He had just transferred to a criminal squad after working counterterrorism cases for years. His first day in the new job was Sept. 11. “I was literally cleaning the desk, I was like wiping the desk when Flight 11 hit the north tower, and it shook our building,” he said. “And I was like, what the heck was that? And later that day, I was transferred back to counterterrorism.” It was a natural move for Zebley. He’d spent the previous three years investigating al-Qaida’s bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. And he became a core member of the FBI team leading the investigation into the 9/11 attacks. It quickly became clear that al-Qaida was responsible.

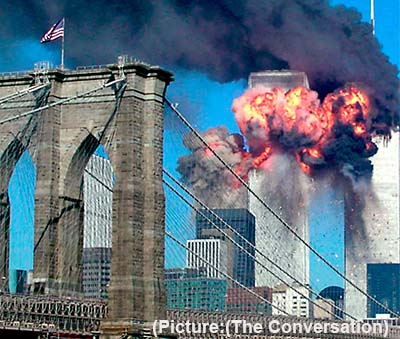

The hijackers had trained at the group’s camps in Afghanistan. They received money and instructions from its leadership. And ultimately, they were sent to the U.S. to carry out al-Qaida’s “planes operation.” President George W Bush gave an address in front of the damaged Pentagon following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack there as Counselor to the President Karen Hughes and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stand by. As the nation mourned the nearly 3,000 people who were killed on 9/11, the George W. Bush administration frantically tried to find its footing and prevent what many feared would be a second wave of attacks. President Bush ordered members of his administration, including top counterterrorism official Richard Clarke, to imagine what the next attack could look like and take steps to prevent it.

The hijackers had trained at the group’s camps in Afghanistan. They received money and instructions from its leadership. And ultimately, they were sent to the U.S. to carry out al-Qaida’s “planes operation.” President George W Bush gave an address in front of the damaged Pentagon following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack there as Counselor to the President Karen Hughes and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stand by. As the nation mourned the nearly 3,000 people who were killed on 9/11, the George W. Bush administration frantically tried to find its footing and prevent what many feared would be a second wave of attacks. President Bush ordered members of his administration, including top counterterrorism official Richard Clarke, to imagine what the next attack could look like and take steps to prevent it.

“We had so many vulnerabilities in this country,” Clarke said. We had a very long list of things, systems, that were vulnerable because no one in the United States had seriously considered security from terrorist attacks. At the time, officials were worried that al-Qaida could use chemical weapons or radioactive materials, Clarke said, or that the group would target intercity trains or subway systems. “We had a very long list of things, systems, that were vulnerable because no one in the United States had seriously considered security from terrorist attacks,” he said. That, of course, quickly changed. Security became paramount. And over the next two decades, the federal government poured money and resources — some of it, critics say, to no good use — into protecting the U.S. from another terrorist attack, even as the nature of that threat continuously evolved.

The response to keeping the U.S. secure takes shape The government built out a massive infrastructure, including creating the Department of Homeland Security, all in the name of protecting against terrorist attacks. The Bush administration also empowered the FBI and its partners at the CIA, National Security Agency and the Pentagon to take the fight to al-Qaida. The military invaded Afghanistan, which had been a haven for the group. The CIA hunted down al-Qaida operatives around the world and tortured many of them in secret prisons. The Bush administration also launched its ill-fated war in Iraq, which unleashed two decades of bloodletting, shook the Middle East and spawned another generation of terrorists.

On the home front, FBI Director Robert Mueller shifted some 2,000 agents to counterterrorism work as he tried to transform the FBI from a crime-fighting first organization into a more intelligence-driven one that prioritized combating terrorism and preventing the next attack. Part of that involved centralizing the bureau’s international terrorism investigations at headquarters and making counterterrorism the FBI’s top priority. Chuck Rosenberg, who served as a top aide to Mueller in those early years, said the changes Mueller imposed amounted to a paradigm shift for the bureau.

“Mueller, God bless him, couldn’t be all that patient about it,” Rosenberg said. “It couldn’t happen at a normal pace of a traditional cultural change. It had to happen yesterday.” It had to happen “yesterday” because al-Qaida was still plotting. Overseas, its operatives carried out horrific bombings in Bali, Madrid, London and elsewhere. In the U.S., al-Qaida operative Richard Reid was arrested in December 2001 after trying to blow up a trans-Atlantic flight with a bomb hidden in his shoe. More plots were foiled in the ensuing years, including one targeting the Brooklyn Bridge. Over time, the FBI and its partners better understood al-Qaida, its hierarchical structure, and how to unravel the various threads of a plot.

That stemmed to large degree, Zebley says, from the U.S. getting better at pulling together various threads of intelligence and by upping the operational tempo. “If you have a little thread that could potentially tell you about a terrorist plot, not only were we much better at integrating the intelligence, but we did it at a pace that was tenfold what we were doing before,” he said. But critics warned that the government’s new anti-terrorism tools were eroding civil liberties, while the American Muslim community felt it was all too often the target of an overzealous FBI.

The digital world helps transform terrorism By the early days of the Obama administration, the U.S. had to a large extent hardened the homeland against 9/11-style plots. But the terrorism landscape was evolving. At that time, Zebley was serving as a senior aide to Mueller. Each morning, he would sit in on the FBI director’s daily threat briefing. “I was thinking about al-Qaida for years leading up until that moment,” he said. “And now I’m sitting in these morning threat briefings and I’m seeing al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb in North Africa, al-Shabab. … One of my first thoughts was ‘the map looks very different to me now.’ ”

Ultimately, AQAP — al-Qaida’s branch based in Yemen — emerged as a significant threat to the U.S. homeland. That became clear in November 2009 when U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Hasan shot and killed 13 people at Fort Hood, Texas. A month later, on Christmas Day, a young Nigerian man tried to blow up a passenger jet over Detroit with a bomb hidden in his underwear. It quickly emerged that both men had been in contact with a senior AQAP figure, an American-born Yemeni cleric named Anwar al-Awlaki.

“My sense when I first heard about him was ‘well, he’s some charismatic guy, born in the U.S., fluent English speaker and all that. But how big a threat could he be?” said John Pistole, who served as the No. 2 official at the FBI from 2004 until 2010 when he left to lead the Transportation Security Administration.

“I think I failed to recognize and appreciate his ability to influence others to action.” Awlaki used the internet to spread his calls for violence against America, and his lectures and ideas influenced attacks in several countries. Awlaki was killed in a U.S. drone strike in 2011, a move that proved controversial because he was an American citizen. A few years later, a different terrorist group emerged from the cauldron of Syria and Iraq — the Islamic State, or ISIS, a group that would build on Awlaki’s savvy use of the digital world. “When ISIS came onto the scene, particularly that summer of 2014, with the beheadings and the prolific use of social media, it was off the charts,” said Mary McCord, who was a senior national security official at the Justice Department at the time.

Like al-Qaida more than a decade before, ISIS used its stronghold to plan operations abroad, such as the coordinated attacks in 2015 that killed 130 people in Paris. But it also used social media platforms such as Twitter and Telegram to pump out slickly produced propaganda videos. “They deployed technology in a much more sophisticated way than we had seen with most other foreign terrorist organizations,” McCord said. ISIS produced materials featuring idyllic scenes of life in the caliphate to entice people to move there. At the same time, the group pushed out a torrent of videos showing horrendous violence that sought to instill fear in ISIS’ enemies and to inspire the militants’ sympathizers in Europe and the U.S. to conduct attacks where they were. “The threat was much more horizontal. It was harder to corral,” said Chuck Rosenberg, who served as FBI Director James Comey’s chief of staff.

People inspired by ISIS could go from watching the group’s videos to action relatively quickly without setting off alarms. “It was clear too that there were going to be attacks we just couldn’t stop. Things that went from left of boom to right of boom very quickly. People were more discreet, the thing we used to refer to as lone wolves,” Rosenberg said. “A lot of bad things could happen, maybe on a smaller scale, but a lot of bad things could happen more quickly.” Bad things did happenEurope was hit by a series of deadly one-off attacks. In the U.S., a gunman killed 49 people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., in 2016. A year later, a man used a truck to plow through a group of cyclists and pedestrians in Manhattan, killing eight people. Both men had been watching ISIS propaganda.