(IPS) -Contrary to the often-cited hype and nonsense of some celebrities reported in the news media, the world’s population of 8,000,000,000 human beings is not going to collapse any time soon.

Moreover, that fancied collapse of world population is neither the biggest problem facing the world nor is that false notion a much bigger risk to civilization than climate change, which is certainly humanity’s greatest challenge.

According to recent projections, the world’s population is expected to continue increasing over the coming decades. Hundreds of millions of more people are projected to be added to the planet, but at a slower pace than during the recent past.

The expected slowdown in the growth of world population does not constitute a problem. The global demographic slowdown clearly signals social, economic, environmental and climatic successes and benefits for human life on planet Earth.

Many of those calling for increased rates of population growth through higher birth rates and more immigration are simply promoting Ponzi demography. The underlying strategy of Ponzi demography is to privatize the profits and socialize the costs incurred from increased population growth.

World population reached the 1 billion milestone in 1804. World population doubled to 2 billion in 1927, doubled again to 4 billion in 1974, and then doubled a third time to 8 billion in 2022

India’s population will likely overtake China’s population by 2023. Picture: Mumbai, India. Credit: Sthitaprajna Jena (CC BY-SA 2.0).

PORTLAND, USA, Nov 8 2022 (IPS) – Contrary to the often-cited hype and nonsense of some celebrities reported in the news media, the world’s population of 8,000,000,000 human beings is not going to collapse any time soon.

Moreover, that fancied collapse of world population is neither the biggest problem facing the world nor is that false notion a much bigger risk to civilization than climate change, which is certainly humanity’s greatest challenge.

According to recent projections, the world’s population is expected to continue increasing over the coming decades. Hundreds of millions of more people are projected to be added to the planet, but at a slower pace than during the recent past.

The expected slowdown in the growth of world population does not constitute a problem. The global demographic slowdown clearly signals social, economic, environmental and climatic successes and benefits for human life on planet Earth.

Many of those calling for increased rates of population growth through higher birth rates and more immigration are simply promoting Ponzi demography. The underlying strategy of Ponzi demography is to privatize the profits and socialize the costs incurred from increased population growth.

World population reached the 1 billion milestone in 1804. World population doubled to 2 billion in 1927, doubled again to 4 billion in 1974, and then doubled a third time to 8 billion in 2022

Throughout the many centuries of human history, the 20th century was an exceptional record-breaking period demographically.

World population nearly quadrupled from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 6.1 billion by the close of the century. In addition, the world’s population annual growth rate peaked at 2.3 percent in 1963 and the annual increase reached a record high of 93 million in 1990.

Since the start of the 21st century, the world’s population has increased by nearly 2 billion people, from 6.1 billion in 2000 to 8 billion in 2022. Over that time period, the world’s annual rate of population growth declined from 1.3 percent to 0.8 percent, with the world’s annual demographic increase going from 82 million to 67 million today.

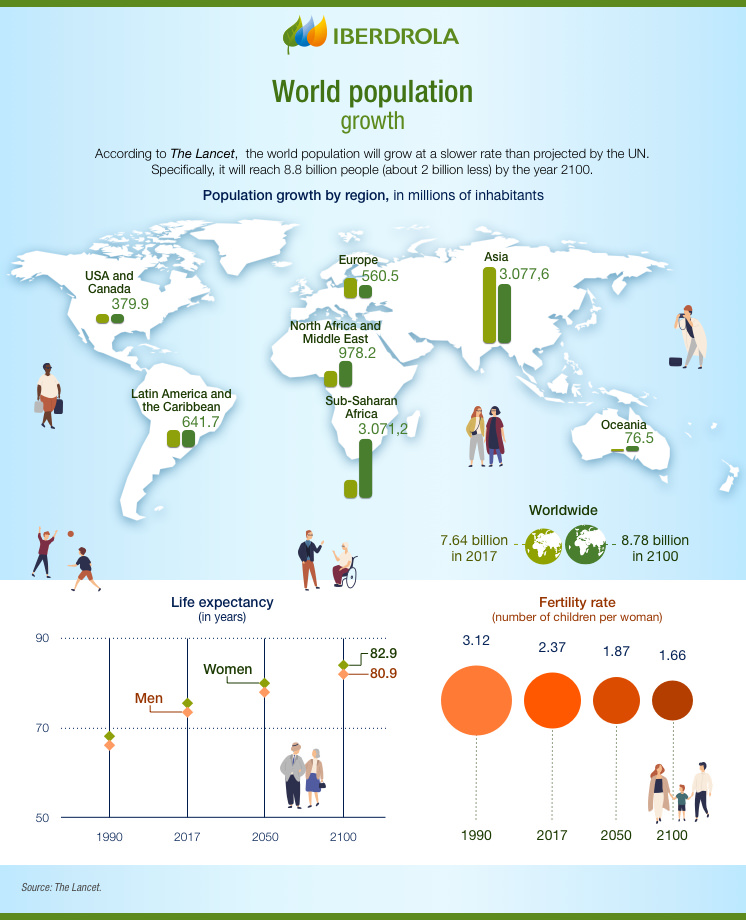

While mortality continues to play an important role in the growth of the world’s population, as witnessed recently with the COVID-19 pandemic, fertility is expected to be the major determinant of the future size of world population.

The world’s average fertility rate of approximately 2.3 births per woman in 2020 is less than half the average fertility rates during the 1950s and 1960s.

The United Nations medium variant population projection assumes fertility rates will continue to decline. By the century’s close the total fertility rate is expected to decline to a global average of 1.8 births per woman, which is one-third the rate of the early 1960s and well below the fertility replacement level.

The medium variant projection results in an increasing world population that reaches 9 billion by 2037, 10 billion by 2058 and 10.3 billion by 2100.

Alternative population projections include the high and low variants, which assume approximately a half child above and below the medium variant, respectively. Accordingly, world population by 2100 ends up being substantially larger in the high variant at 14.8 billion and substantially smaller in the low variant at 7.0 billion (Figure 2).

Another alternative population projection, which is unlikely but instructive, is the constant variant. That projection variant assumes the current fertility rates of countries remain unchanged or constant at their current levels throughout the remainder of the 21st century. The constant variant results in a projected world population at the close of the century that is more than double its current size, 19.2 versus 8.0 billion.

Although world population is projected to continue increasing over the coming decades, considerable diversity exists in the future population growth of countries.

The populations of some 50 countries, including China, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, South Korea and Spain, are expected to decline in size by midcentury due to low fertility rates. At the same time, the populations of about two dozen other countries, including Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Niger, Somalia and Sudan, are expected to increase substantially due to their comparatively high fertility rates.

A comparison of the growth of the populations according to the medium variant for the four projected largest countries by midcentury, i.e., China, India, Nigeria, and the United States, highlights the diversity of population growth expected during the 21st century.

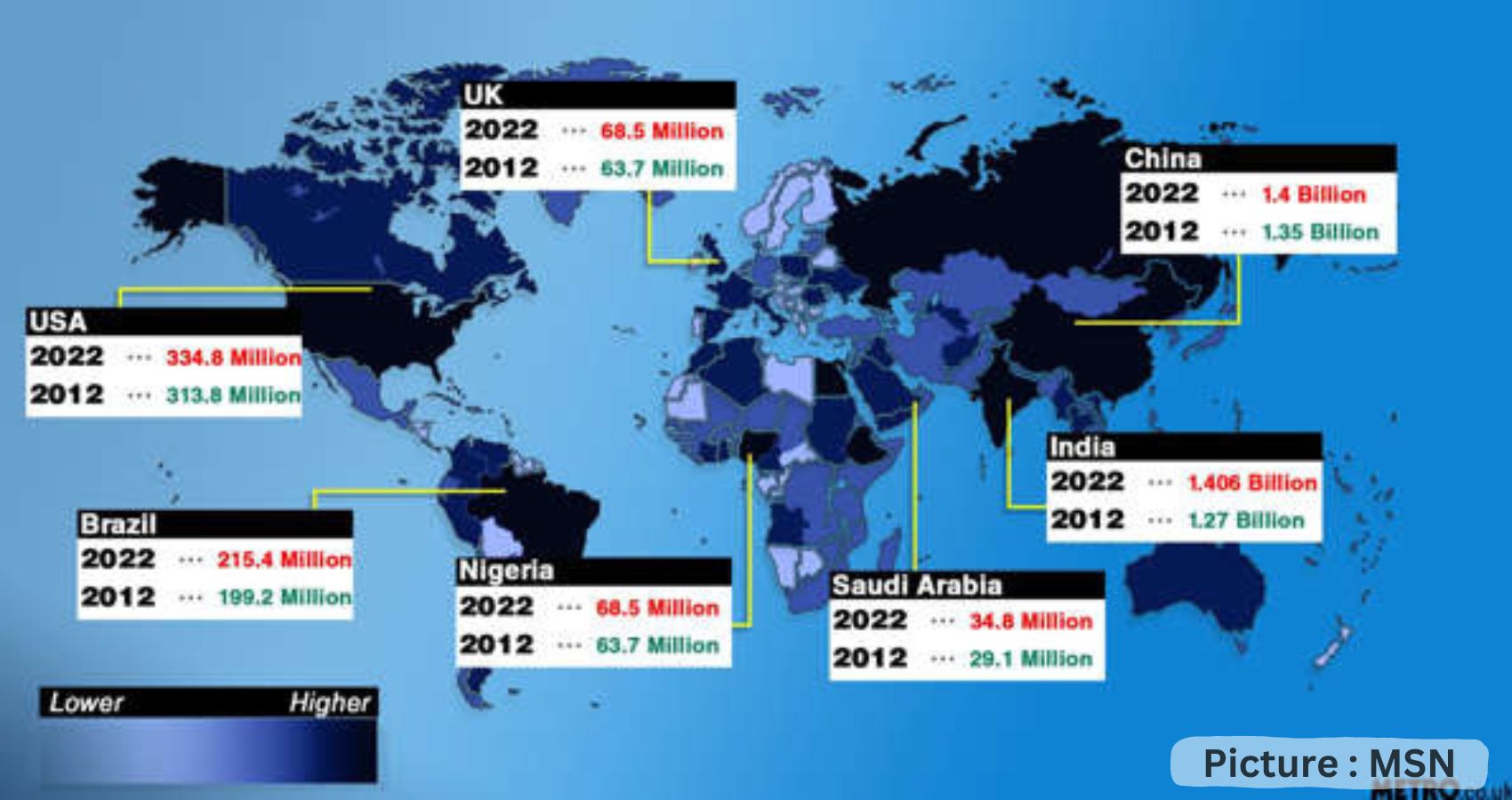

China’s current population size is estimated to be near its peak at approximately 1.4 billion. Due to its fertility rate of 1.16 births per woman, which is close to half the replacement level and is assumed to remain relatively low over the coming decades, the Chinese population is expected to decline to 1.3 billion by 2050 and decline further to 0.8 billion by 2100.

In contrast, India’s population, which has an estimated fertility rate of 2.0 births per woman that is expected to decline further, is continuing to increase in size. As a result of that demographic growth, India’s population will likely overtake China’s population by 2023. By 2060 India’s population is projected to peak at 1.7 billion and decline to 1.5 billion by 2100 (Figure 3).

The population of the United States, currently the third world’s largest population after China and India, is expected to continue increasing in size largely due to immigration. By 2050 the U.S. population is projected to reach 375 million and be close to 400 million by the century’s close.

Nigeria’s rapidly growing population, which more than doubled over the past 30 years from 100 million in 1992 to 219 million in 2022, is expected to continue its rapid demographic growth for the remainder of the century. The population of Nigeria is expected to be larger than the U.S. population by 2050, when it reaches 377 million, and then increase to 500 mil1ion in 2077 and 546 million by the century’s close.

Admittedly, the future size of the world’s population remains uncertain. Demographic conditions, especially mortality levels as recently witnessed with the COVID-19 pandemic, could change markedly and future fertility rates may also follow different patterns from those being assumed in the most recent population projections.

Nevertheless, it appears that the world’s current population of 8 billion will continue increasing over the coming decades, likely gaining an additional 2 billion people by around midcentury.

The expected demographic growth of the world’s population of 8 billion during the 21st century poses daunting challenges. Prominent among those challenges are dire concerns about food, water and energy supplies, natural resources, biodiversity, pollution, the environment, and of course climate change, considered by most, including the world’s scientists, to be humanity’s greatest challenge.

(Joseph Chamie is an independent consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters.”)

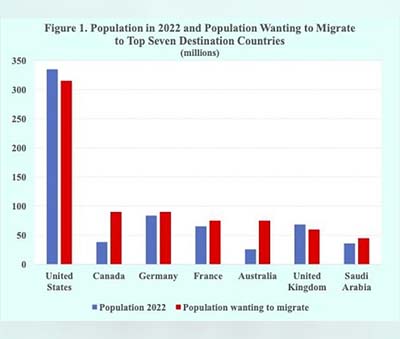

Seven destination countries attract half of those wanting to migrate to another country. The top destination country at 21 percent of those wanting to migrate is the United States. Substantially lower, Canada and Germany are next at 6 percent, followed by France and Australia at 5 percent, the United Kingdom at 4 percent, and Saudi Arabia at 3 percent

Seven destination countries attract half of those wanting to migrate to another country. The top destination country at 21 percent of those wanting to migrate is the United States. Substantially lower, Canada and Germany are next at 6 percent, followed by France and Australia at 5 percent, the United Kingdom at 4 percent, and Saudi Arabia at 3 percent