The health of democracy has declined significantly in many nations over the past several years, but the concept of representative democracy continues to be popular among citizens across the globe.

Solid majorities in each of the 24 countries surveyed by Pew Research Center in 2023 describe representative democracy, or a democratic system where representatives elected by citizens decide what becomes law, as a somewhat or very good way to govern their country.

However, enthusiasm for this form of government has slipped in many nations since 2017. And the survey highlights significant criticisms of the way it’s working. Across the countries included in the study:

- A median of 59% are dissatisfied with how their democracy is functioning.

- 74% thinkelected officials don’t care what people like them think.

- 42% say nopolitical party in their country represents their views.

What is a median?

Throughout this report, median scores are used to help readers see overall patterns in the data. The median percentage is the middle number in a list of all percentages sorted from highest to lowest.

What – or who – would make representative democracy work better?

Many say policies in their country would improve if more elected officials were women, people from poor backgrounds and young adults.

Electing more women is especially popular among women, and voting more young people into office is particularly popular among those under age 40.

Views are more mixed on the impact of electing more businesspeople and labor union members.

Overall, there is less enthusiasm for having more elected officials who are religious, although the idea is relatively popular in several middle-income nations (Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria and South Africa, as defined by the World Bank).

For this report, we surveyed 30,861 people in 24 countries from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023. In addition to this overview, the report includes chapters on:

- Attitudes toward different types of government systems

- Views about political representation

- Impact of electing more officials from different backgrounds

- Satisfaction with democracy and ratings for specific leaders and parties

Read some of the report’s key findings below.

How do views of democracy stack up against nondemocratic approaches?

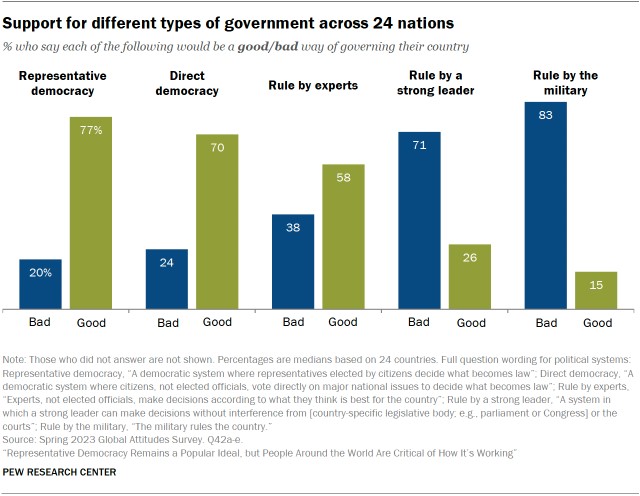

Even though most people believe representative democracy is a good way to govern, many are open to other forms of government as well.

Direct democracy – a system where citizens, rather than elected officials, vote directly on major issues – is also viewed favorably by majorities in nearly all countries polled.

In most countries, expert rule – in which experts, not elected officials, make key decisions – is also a popular alternative.

And there is notable support for more authoritarian models of government.

In 13 countries, a quarter or more of those surveyed think a system in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliament or the courts is a good form of government. In four of the eight middle-income nations in the study, at least half of respondents express this view.

Even military rule has its supporters, including about a third or more of the public in all eight middle-income countries. There is less support in high-income nations, although 17% say military rule could be a good system in Greece, Japan and the United Kingdom, and 15% hold this view in the United States.

Views on representative democracy

Views on representative democracy

Strong support for representative democracy has declined in many nations since we last asked the question in 2017.

The share of the public describing representative democracy as a very good way to govern is down significantly in 11 of the 22 countries where data from 2017 is available (trends are not available in Australia and the U.S.).

For instance, 54% of Swedes said representative democracy was a very good approach in 2017, while just 41% hold this view today.

In contrast, strong support for representative democracy has risen significantly in three nations (Brazil, Mexico and Poland).

Views on autocratic leadership

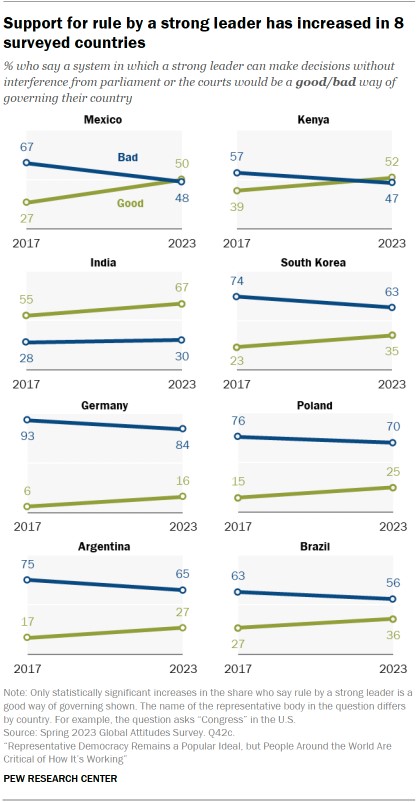

Support for a government where a strong leader can make decisions without interference from courts or parliaments has increased in eight of 22 nations since 2017.

Support for a government where a strong leader can make decisions without interference from courts or parliaments has increased in eight of 22 nations since 2017.

It is up significantly in all three Latin American nations polled, as well as in Kenya, India, South Korea, Germany and Poland.

Support for a strong leader model is especially common among people with less education and those with lower incomes.

People on the ideological right are often more likely than those on the left to support rule by a strong leader.

Views on expert rule

Support for a system where experts, not elected officials, make key decisions is up significantly in most countries since 2017, and current views of this form of government may be tied at least in part to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in the U.S., 59% of those who believe public health officials have done a good job of responding to the coronavirus outbreak think expert rule is a good system, compared with just 35% among those who say public health officials have done a bad job of dealing with the pandemic.

Widespread belief that elected officials are out of touch

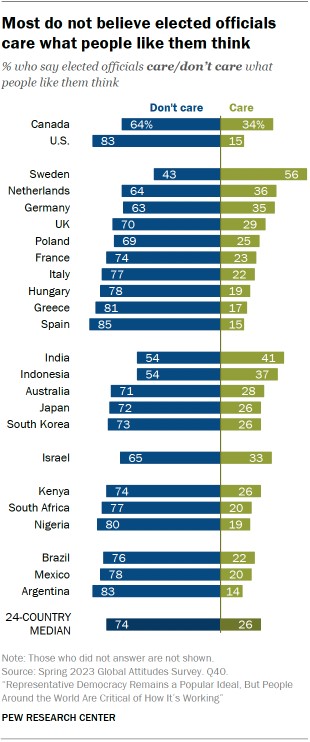

One factor driving people’s dissatisfaction with the way democracy is functioning is the belief that politicians are out of touch and disconnected from the lives of ordinary citizens.

One factor driving people’s dissatisfaction with the way democracy is functioning is the belief that politicians are out of touch and disconnected from the lives of ordinary citizens.

In every country surveyed, people who feel politicians don’t care about people like them are less satisfied with democracy.

Across 24 nations, a median of 74% say elected officials in their country don’t care what people like them think.

At least half of those surveyed hold this view in all countries but one (Sweden). Opinions about elected officials are particularly negative in Argentina, Greece, Nigeria, Spain and the U.S., where at least eight-in-ten believe elected officials don’t care what people like them think.

Many don’t think political parties represent them

While a median of 54% across the 24 countries surveyed say there is at least one party that represents their views well, 42% say there is no party that represents their views.

Israelis, Nigerians and Swedes are the most likely to say at least one party represents their opinions – seven-in-ten or more express this view in each of these countries.1 In contrast, about four-in-ten or fewer say this in Argentina, France, Italy and Spain. Americans are evenly divided on this question.

In 18 countries where we asked about ideology, people who place themselves in the center are especially likely to feel unrepresented. And in some countries, those on the right are particularly likely to say there is at least one party that represents their views.

The U.S. illustrates this pattern: 60% of American conservatives say there is a party that represents their opinions, compared with 52% of liberals and just 40% of moderates.

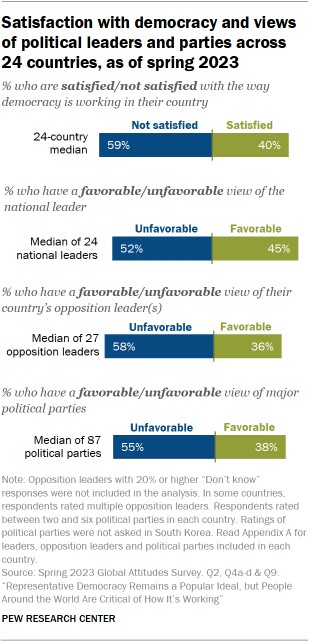

People rate their country’s leaders, parties and overall state of democracy poorly

The survey asked respondents how well they feel democracy is working in their country, and it also asked them to rate major national leaders and parties. Opinions on these questions may have shifted since the survey was conducted in spring 2023, but the overall results provide a relatively grim picture of the political mood in many nations. (Refer to Appendix A for details about the specific leaders and parties we asked about.)

rate major national leaders and parties. Opinions on these questions may have shifted since the survey was conducted in spring 2023, but the overall results provide a relatively grim picture of the political mood in many nations. (Refer to Appendix A for details about the specific leaders and parties we asked about.)

- There are only seven countries where half or more are satisfied with the way democracy is working.

- Among the 24 national leaders included on the survey, just 10 are viewed favorably by half or more of the public.

- Opposition leaders fare even worse – only six get favorable reviews.

- Across the countries polled, we asked about 87 different political parties. Just 21 get a positive rating.

- Opinions vary greatly across regions and countries, but to some extent, we see more positive views about leaders and parties in middle-income nations.

How ideology relates to views of representation

This report highlights significant ideological differences on many questions, including preferences regarding the characteristics of people who serve as elected officials.

Those on the political left are generally much more likely than those on the right to favor electing more labor union members, young adults, people from poor backgrounds and women.

Meanwhile, those on the right are more likely to say policies would improve if more religious people and businesspeople held elective office.

Ideological divisions on these topics are often especially sharp in the U.S. There are also very large partisan differences.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are much more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to favor having more women, young adults, people from poor backgrounds and labor union members in office.

Meanwhile, Republicans are more likely to endorse electing more religious people and businesspeople.

In their own words: Ideas for improving democracy

The survey also included the following open-ended question: “What do you think would help improve the way democracy in this country is working?” Respondents describe a wide variety of ideas for making democracy work better, but a few common themes emerge:

Improving political leadership:Respondents want politicians who are more responsive to the public’s needs, more attentive to the public’s voice, less corrupt and more competent. Many would also like political leaders to be more representative of their country’s population in terms of gender, age, race and other factors.

Government reform:Many believe improving democracy will require significant political reform in their country. Views about what reform should look like vary considerably, but suggestions include changing electoral systems, shifting the balance of power between institutions, and placing limits on how long politicians and judges can serve. In several countries, people express a desire for more direct democracy.

Expecting more from citizens: Respondents also emphasize that citizens have an important role to play in making democracy work better. They argue that citizens need to be more informed, engaged, tolerant and respectful of one another.

Improving the economy: Many people – and especially those in middle-income nations – emphasize the link between a healthy economy and a healthy democracy. Respondents mention creating jobs; curbing inflation; changing government spending priorities; and investing more in infrastructure, such as roads, hospitals, water, electricity and schools.

The full results of the open-ended question will be released in an upcoming Pew Research Center report. For a preview of some of the findings, read “Who likes authoritarianism, and how do they want to change their government?”

Additional reports and analyses

Pew Research Center regularly explores public attitudes toward democracy and related issues around the world. The Center also regularly examines U.S. public opinion on topics related to democracy. Some of the most recent releases include:

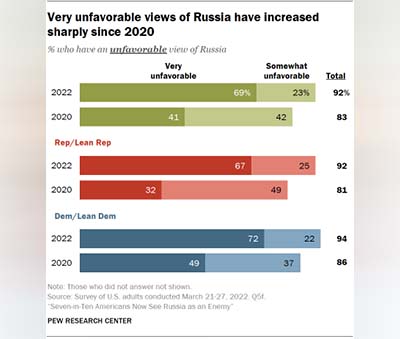

While negative sentiment toward Russia has increased substantially among both Democrats and Republicans since 2020, Republicans’ views have changed more drastically. Around a third of Republicans and Republican leaners had a very unfavorable view of Russia in 2020, compared with 67% who now hold this view – a 35 percentage point increase. In the same period, the share of Democrats with a very negative view of Russia increased by 23 points. A small partisan gap in views of Russia remains, but Republicans and Democrats are not as divided on Russia as they once were.

While negative sentiment toward Russia has increased substantially among both Democrats and Republicans since 2020, Republicans’ views have changed more drastically. Around a third of Republicans and Republican leaners had a very unfavorable view of Russia in 2020, compared with 67% who now hold this view – a 35 percentage point increase. In the same period, the share of Democrats with a very negative view of Russia increased by 23 points. A small partisan gap in views of Russia remains, but Republicans and Democrats are not as divided on Russia as they once were. Americans of all ages tend to have favorable opinions of NATO overall, but those ages 65 and older are more likely to hold a favorable view of NATO than younger adults. Roughly three-quarters (73%) of older Americans have a positive opinion of the organization, compared with 64% of those ages 18 to 29. Eight-in-ten of those with a postgraduate degree express a favorable opinion of NATO – significantly more than the share with a bachelor’s degree (73%), some college (64%) or a high school degree or less (59%).

Americans of all ages tend to have favorable opinions of NATO overall, but those ages 65 and older are more likely to hold a favorable view of NATO than younger adults. Roughly three-quarters (73%) of older Americans have a positive opinion of the organization, compared with 64% of those ages 18 to 29. Eight-in-ten of those with a postgraduate degree express a favorable opinion of NATO – significantly more than the share with a bachelor’s degree (73%), some college (64%) or a high school degree or less (59%).