Several years of meticulous planning, discussions, and organization, came to fruition as 190 delegates of American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI) Families and Friends from across the United States and India embarked on the Ocean Atlantic Ship operated by Albatros Expeditions on November 30th, 2019 from Ushuaia, the southernmost town on Earth in Argentina on a voyage to Antarctica, the seventh Continent, known as the Last Horizon on Earth.

The voyagers were welcomed on board by AAPI’s young and dynamic President, Dr. Suresh Reddy, who has been working very hard, coordinating the efforts with Vinod Gupta from the Travel Agency, ATG Tours, the crew and leadership of the Cruise and the AAPI leaders and members with varied interests and ages ranging from 10 to 90, who had flown in from around the world for this once in a lifetime memorable and historic voyage to the White Continent.

Earlier, the AAPI delegates had toured the beautiful and serene National Park in Ushuaia, on the world famous Route 3 that runs from Alaska to the southern tip of the world in Argentina. At the Park, Dr. Reddy led the AAPI delegates carrying the AAPI banner, spreading the message of Obesity Awareness, which is a major objective of Dr. Reddy’s Presidency, taking the message of Obesity Awareness Around the World.

On the Ship, immediately after settling down in each one’s cabin, the voyagers were invited to learn about safety on the ship and participated in a safety drill. Shelli Ogilvy, the Veteran Expedition Leader introduced the 22 Expedition Members with extensive maritime experiences from around the world, and over 60 other crew members to the voyagers.

On the Ship, immediately after settling down in each one’s cabin, the voyagers were invited to learn about safety on the ship and participated in a safety drill. Shelli Ogilvy, the Veteran Expedition Leader introduced the 22 Expedition Members with extensive maritime experiences from around the world, and over 60 other crew members to the voyagers.

The Ship carrying the sailors began its journey on November 30th, 2019 from the Ushuaia Sea Port with a prayer song to Lord Ganesh, chanted by Dr. Aarti Pandya from Atlanta, GA.

Later in the evening, the voyagers sat down for a sit down dinner at the elegantly laid tables at the Restaurant with delicious Indian Cuisine, prepared by Herbert Baretto, a Chef from Goa, India, specially flown in to meet the diverse needs of the Indians who are now the exclusive Voyagers on Ocean Atlantic.

The evenings are fun filled with members spending time together with their select friends and families, singing, playing cards games, discussing politics to medicine to healthcare and sharing jokes and snippets with one another in smaller groups. The cultural events included live music sung by Dr. Radhika from Chicago, Dr. Aarti Pandya and Dr. Badlani, in addition to several local talents of AA{I’s own, leading and vying to win the Anthakshri contest.

The finale on December 8th was a colorful Indian Dress Segment, where the adorable AAPI women and men walked the aile in elegantly dressed in Indian ethnic wear depicting different states of India. On December 7th evening, the voyagers had Black Tie Nite with many of them learning and playing Pokers until the early hours of the morning.

As the sun was still shining beyond midnight, members of the voyage were seen posing and taking pictures on board the ship with the background of the mighty ocean and the scenic mountains of Argentina at the background.

On December 1st morning, AAPI members were alerted to be mindful of the most turbulent Drake Passage, where the Pacific and the Atlantic Ocean merge, through which our ship was now sailing with winds gusting through over 50 kms an hour from the south west. The rough with fast moving sea currents contributing to a turbulent weather, several voyagers took shelter in anti-nausea meds.

Throughout the day, there were special safety classes periodically throughout the day, helping the voyagers on ways to navigate the zodiacs, the kayaks, the walks on the ice and snow once we reach our final destination. They were also educated on the many aspects of wildlife on Antarctica, the species, especially the varieties of penguins, the mammals and the birds that inhabit the Continent and the ways for the voyagers to deal with them. The participants were educated on the Antarctic Treaty, Climate Change and Impact, Whale Hunting, and many more relevant topics with scientific data by the Expedition Crew.

The evening was special for the voyagers as the Captain of the ship welcomed the delegates to the Ship and to the Expedition to Antarctica. He introduced his crew leaders to the loud applause from the delegates, as he toasted champagne for a safe and enjoyable journey to Antarctica.

On December 2nd morning, we woke up to milder weather and calmer ocean with the winds subsiding to about 20 kms an hour and ship sailing smoother with the temperatures below 7 degree Celsius. The crew on the ship described the sail to be the smoothest and the weather and wind conditions to be one of the calmest they have ever witnessed. However, the entire day was cloudy with the sun hiding behind the thick clouds upon the ocean.

AAPI in Antarctica

After sailing across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans and through the turbulent Drake Passage, and the South Ocean, finally, the day arrived for the Voyagers. The one they had been eagerly waiting for. On December 3rd, our ship, the Ocean Atlantic anchored on Danco Island, off the coast of the 7th Continent, Antarctica, officially discovered in 1820, although there is some controversy as to who sighted it first

After sailing across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans and through the turbulent Drake Passage, and the South Ocean, finally, the day arrived for the Voyagers. The one they had been eagerly waiting for. On December 3rd, our ship, the Ocean Atlantic anchored on Danco Island, off the coast of the 7th Continent, Antarctica, officially discovered in 1820, although there is some controversy as to who sighted it first

The excitement of the voyagers had no bounds as they dressed up in their waterproof trousers, navy blue jackets, with hats and glouce and mufflers. They set out in groups marching off the Ship into the Zodiacs in tens in each Zodiac.

The wind and the ocean were calmer. The sun continued to hide behind thick clouds. The Expedition Crew from the ship drove the AAPI delegates to the shore on the island for the first time. The glaciers, mighty mountains covered with pristine and shiny snow, the icebergs on the ocean floating on the Bay, made the Zodiac ride to the shore a memorable experience for each.

As the voyagers walked to the shore on a narrow path on the soft snow surface, leading up the snowcapped mountains, it was a dream come true for all. The fresh water melting from the glaciers and the ice on the one side and on the other little rocks and mountains filled with snow, the Danco Island was picture perfect.

Head off in a Zodiac to view icebergs, or land on a beach studded with penguins. Kayak in the greatest silence on Earth. Take a long hike or a short walk on a shore lined with ghostly remnants of the whaling industry.

Penguins in small colonies of their own seemed unaffected by the voyagers landing onto the Penguin land. Hearing their unique and enchanting voices for the first time, as most of them sat steady, while a few walked from one end to the other, it was a scene everyone long dreamt to be part of, as it was another memorable experience in the life of everyone.

In the afternoon, after lunch and a lecture on the history of Antarctica, the Ocean Atlantic ship, travelling about 25 nautical miles, for the first time ever, landed on the Antarctic Continent as she reached the shores of Paradise Bay, a beautiful island, where the famous Brown Center, the Argentinian Research Station was located.

In the afternoon, after lunch and a lecture on the history of Antarctica, the Ocean Atlantic ship, travelling about 25 nautical miles, for the first time ever, landed on the Antarctic Continent as she reached the shores of Paradise Bay, a beautiful island, where the famous Brown Center, the Argentinian Research Station was located.

Trekking up the Hill on the snow and ice filled terrains, even as the serene and picturesque glaciers in vivid shapes and texture, it was mesmerizing and the Bay on either side, was breathtaking.

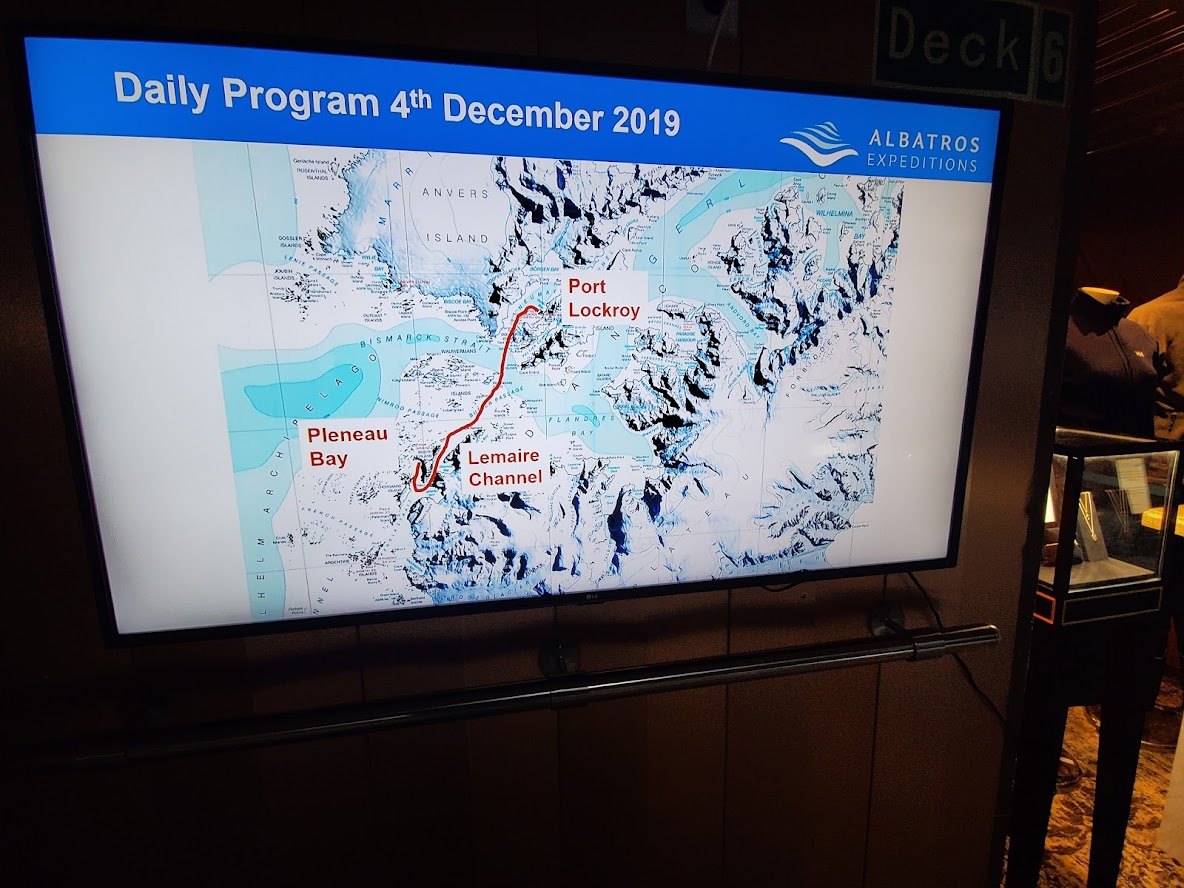

On December 4th morning, the voyagers got onto the Zodiacs and sailed to Port Lockroy, a sheltered harbor with a secure anchorage on the Antarctic Peninsula since its discovery in 1904. The Port also is home to a Museum and a British Post Office, where the early visitors to the Continent lived and explored the wildlife of the last Horizon. The Museum has preserved the antiques used by the early voyagers, who are an important part in the history of Antarctica.

Bright sun light flashing on the Lamoy Point on our way south towards the northern peninsula of the white Coneinent greeted us all this morning on December 5th. The greetings over the microphone at 6.15 woke us all up letting us know of the .mild weather conditions with 7 degrees celcius and 27 km s wind speed with bright sunny day was a welcome change from yesterday.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

Bright sun light flashing on the Lamoy Point on our way south towards the northern peninsula of the white Coneinent greeted us all this morning on December 5th. The greetings over the microphone at 6.15 woke us all up letting us know of the .mild weather conditions with 7 degrees celcius and 27 km s wind speed with bright sunny day was a welcome change from yesterday.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

The wind of 25 kms an hour made the waters of the Bay mildly rough as we set out from the ship. For the first time during the voyage, to the much delight of the AAPI delegates, the sun chose to come out from behind the clouds and shone brightly on the voyagers, making the snow shining and glowing with the rays of the sun filling the surface of the earth. It was delightful to see the Penguins close to the AAPI delegates, some of them walking beside them crossing their pathway.

After a lunch Barbeque on Deck Seven of the Ship, the Ocean Atlantic took us through the beautiful Lemaire Channel on the Continent. Braving the cold and gusty winds, the voyagers got together for a group picture of the entire voyager group on Deck Eight of the ship, as they were awed by the beautiful glaciers, the mighty snow-caped mountains, and the floating ice bergs.

It was an amazing experience as the Ship sailed through the Bay filled with Ice Sheet Rocks that are over a meter thick, slowly but steadily marching forward towards the Plenau Bay, where the 38 brave AAPI members had the unique experience of taking “Polar Plunge” in the Sea Water, which was 0.78 degree calcium while the rest of the AA{I delegates watched the brave men and women taking a memorable dip and swim back to the ship in the freezing cold waters of the Antarctic Continent.

This afternoon we were invited to climb up to the Decks 8 and 9 of the ship to view the entrance/passage to the famous Deception Island. Ad the ship sailed through this narrow path into the Island with majestic dark mountains on our right side while on the left snowcapped mountains overlooking the Bay. As the gusty winds made us shiver the voyagers standing on the top deck of the Atlantic Ocean posed for pictures while many others were lost in the stunning beauty created by Mother Nature for all of us to enjoy and cherish for ever.

The tallest mountain Mount Franceswithe height of 2300 meters high behind the backdrop, our zodiacs elegantly cruised fhrough the calmer waters to the mountain range called the Princes and the seven dwarfs.

The stunning views of the glaciers and the mountains and the soft and shiny snow spread across the shore led us all to the top of the snowy hills as we trekked to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Many if us waited patiently to have an opportunity to view the eggs upon which the Penguins were sitting to hatch their eggs. Some were lucky to photograph a few couples mating while we were trying to figure out the male from female.

Leaving the breath taking landscapes was not an easy choice as we were soon called to embark on the zodiacs and return to Ocean Atlantic our ship as she was patiently waiting to take us to the next destination of our expedition to the Last Horizon.

We woke up this morni g on Friday December 6th to a bright and sunny day, calmer ocean with 9 kms of wind speed….a picture perfect day for expedition.

We went on zodiacs cruising through the blue waters of the Half Moon Island, a cluster of snowy mountains shaped as a half moon. Searching for wild life in the ocean with the voyagers looking out eagerly for any seals or whales did not seem to result in success as the sea animals and those on the shore seemed to hide in their resting places.

Finally the zodiac captains took us to the shore where for the first time we landed on dark stony surface full of rocks stones and pebbles. Our expedition crew leader reported that the shore was completely covered with ice and snow in the beginning of the season barely a month ago.

The glaciers and the imposing mighty mountains around us we hiked up the hill intruding sometimes into the Penguin Hoghways where we saw colonies of penguins resting under the bright sun. It was delightful to watch a few hopping on tiny rocks from one to another unnerved by the visitors from the Other Continents on earth.

A relaxing and rejuvenating morning walks across the island with breath taking views in abundance of Mother Nature will last a life time for everyone who has been part of the historic expedition to the 7th Continent.

After journeying about five hours we reached this evening at the Melchiors Island as the bright sun shining on us. On our way during lunch and later on the voyagers were thrilled to spot whales showing up their heads periodically.

The journey through the Bay was another memorable experience with the stunning landscape all along the route especially as the sun continued shine brightly on the snow peaked mountains turning the waters closer the glaciers turning from blue to green.

We had over an hour of zodiac cruise exploring the sea life on the Antarctic’s South Ocean.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

We spotted a few huge Cedder Seals resting on the rocks unmoved by the voyagers in several zodiacs watching them in awe.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

190 Members of American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin AAPI under the leadership of Dr. Suresh Reddy and a over 50 strong crew and 22 member expedition team set on sail from Urshuaia the southernmost township on earth located in the beautiful country Argentina on Saturday November 30th 2019

The AAPI delegates came from across the United States with some members of the extended family of AAPI delegates coming from india on this once in a lifetime experience to the sea enth continent Antarctica.

Earlier the AAPI delegates spent a day in Urshuia touring the National Park and lake wearing yellow hats and shirts carrying a banner spreading the message of the need for obesity awareness.

On the ship the voyage to the White continent began with a Prayer song by Dr.Aarti Pandya from Atlanta to Lord Ganesha seeking his blessings and prayers to remove all obstacles out of the way.

The sit down dinner on the first night as the ship sailed through the passage towards the south ocean was an amazing experience even as the sun shone on the west until 11 pm.

The 2nd day the Voyagers were woken up by announcement from crew of heavy winds of 50 km an hour and rough sea as the majestic ship moved ahead with braving the tumultuous weather and mighty ocean.

The 2nd night on the ship was special with the captain hosting the dinner and the delegates interacting with the crew and the delegates.

AAPI’s Historic Expedition

Today, on December 4th, the voyagers got onto the Zodiacs and sailed to Port Lockroy, a sheltered harbor with a secure anchorage and the Antarctic Peninsula since its discovery in 1904. The Port also is home to a Museum and a British Post Office, where the early visitors to the Continent lived and explored the wildlife of the last Horizon. The Museum has preserved the antiques used by the early voyagers, which is an important role in the history of Antarctica.

Today, on December 4th, the voyagers got onto the Zodiacs and sailed to Port Lockroy, a sheltered harbor with a secure anchorage and the Antarctic Peninsula since its discovery in 1904. The Port also is home to a Museum and a British Post Office, where the early visitors to the Continent lived and explored the wildlife of the last Horizon. The Museum has preserved the antiques used by the early voyagers, which is an important role in the history of Antarctica.

The wind of 25 kms an hour made the waters of the Bay mildly rough as we set out from the ship. For the first time during the voyage, to the much delight of the AAPI delegates, the sun chose to come out from behind the clouds and shone brightly on the voyagers, making the snow shining and glowing with the rays of the sun filling the surface of the earth. It was delightful to see the Penguins close to the AAPI delegates, some of them walking beside them crossing their pathway.

After a lunch Barbeque on Deck Seven of the Ship, the Ocean Atlantic took us through the beautiful Lemaire Channel on the Continent. Braving the cold and gusty winds, the voyagers got together for a group picture of the entire voyager group on Deck Eight of the ship, as they were awed by the beautiful glaciers, the mighty snow-caped mountains, and the floating ice bergs.

It was an amazing experience as the Ship sailed through the Bay filled with Ice Sheet Rocks that are over a meter thick, slowly but steadily marching forward towards the Plenau Bay, where the 38 brave AAPI members had the unique experience of taking “Polar Plunge” in the Sea Water, which was 0.78 degree calcium while the rest of the AA{I delegates watched the brave men and women taking a memorable dip and swim back to the ship in the freezing cold waters of the Antarctic Continent.

Bright sun light flashing on the Lamiy Bay on our way up north towards the northern peninsula of the white Coneinent greeted us all this morning on December 5th. The greetings over the microphone at 6.15 woke us all up letting us know of the .mild weather conditions with 7 degrees celcius and 27 km s wind speed with bright sunny day was a welcome change from yesterday.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

The tallest mountain Mount Franceswithe height of 2300 meters high behind the backdrop, our zodiacs elegantly cruised fhrough the calmer waters to the mountain range called the Princes and the seven dwarfs.

The stunning views of the glaciers and the mountains and the soft and shiny snow spread across the shore led us all to the top of the snowy hills as we trekked to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Many if us waited patiently to have an opportunity to view the eggs upon which the Penguins were sitting to hatch their eggs. Some were lucky to photograph a few couples mating while we were trying to figure out the male from female.

Leaving the breath taking landscapes was not an easy choice as we were soon called to embark on the zodiacs and return to Ocean Atlantic our ship as she was patiently waiting to take us to the next destination of our expedition to the Last Horizon.

After journeying about five hours we reached this evening at the Melchiors Island as the bright sun shining on us. On our way during lunch and later on the voyagers were thrilled to spot whales showing up their heads periodically.

The journey through the Bay was another memorable experience with the stunning landscape all along the route especially as the sun continued shine brightly on the snow peaked mountains turning the waters closer the glaciers turning from blue to green.

We had over an hour of zodiac cruise exploring the sea life on the Antarctic’s South Ocean.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

We spotted Seals resting on the rocks unmoved and unaffected by the voyagers in several zodiacs watching them in awe.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

Sent from my Verizon, Samsung Galaxy smartphone

Bright sun light flashing on the Lamiy Bay on our way up north towards the northern peninsula of the white Coneinent greeted us all this morning on December 5th. The greetings over the microphone at 6.15 woke us all up letting us know of the .mild weather conditions with 7 degrees celcius and 27 km s wind speed with bright sunny day was a welcome change from yesterday.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

The tallest mountain Mount Franceswithe height of 2300 meters high behind the backdrop, our zodiacs elegantly cruised fhrough the calmer waters to the mountain range called the Princes and the seven dwarfs.

The stunning views of the glaciers and the mountains and the soft and shiny snow spread across the shore led us all to the top of the snowy hills as we trekked to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Many if us waited patiently to have an opportunity to view the eggs upon which the Penguins were sitting to hatch their eggs. Some were lucky to photograph a few couples mating while we were trying to figure out the male from female.

Leaving the breath taking landscapes was not an easy choice as we were soon called to embark on the zodiacs and return to Ocean Atlantic our ship as she was patiently waiting to take us to the next destination of our expedition to the Last Horizon.

After journeying about five hours we reached this evening at the Melchiors Island as the bright sun shining on us. On our way during lunch and later on the voyagers were thrilled to spot whales showing up their heads periodically.

The journey through the Bay was another memorable experience with the stunning landscape all along the route especially as the sun continued shine brightly on the snow peaked mountains turning the waters closer the glaciers turning from blue to green.

We had over an hour of zodiac cruise exploring the sea life on the Antarctic’s South Ocean.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

We spotted a few huge Cedder Seals resting on the rocks unmoved by the voyagers in several zodiacs watching them in awe.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

After journeying about five hours we reached this evening at the Melchiors Island as the bright sun shining on us. On our way during lunch and later on the voyagers were thrilled to spot whales showing up their heads periodically.

The journey through the Bay was another memorable experience with the stunning landscape all along the route especially as the sun continued shine brightly on the snow peaked mountains turning the waters closer the glaciers turning from blue to green.

We had over an hour of zodiac cruise exploring the sea life on the Antarctic’s South Ocean.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

We spotted a few huge Cedder Seals resting on the rocks unmoved by the voyagers in several zodiacs watching them in awe.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

We woke up this morni g on Friday December 6th to a bright and sunny day, calmer ocean with 9 kms of wind speed….a picture perfect day for expedition.

We went on zodiacs cruising through the blue waters of the Half Moon Island, a cluster of snowy mountains shaped as a half moon. Searching for wild life in the ocean with the voyagers looking out eagerly for any seals or whales did not seem to result in success as the sea animals and those on the shore seemed to hide in their resting places.

Finally the zodiac captains took us to the shore where for the first time we landed on dark stony surface full of rocks stones and pebbles. Our expedition crew leader reported that the shore was completely covered with ice and snow in the beginning of the season barely a month ago.

The glaciers and the imposing mighty mountains around us we hiked up the hill intruding sometimes into the Penguin Hoghways where we saw colonies of penguins resting under the bright sun. It was delightful to watch a few hopping on tiny rocks from one to another unnerved by the visitors from the Other Continents on earth.

A relaxing and rejuvenating morning walks across the island with breath taking views in abundance of Mother Nature will last a life time for everyone who has been part of the historic expedition to the 7th Continent.

This afternoon we were invited to climb up to the Decks 8 and 9 to view the entrance/passage to the famous Deception Island. Ad the ship sailed through this narrow path into the Island with majestic dark mountains on our right side while on the left snowcapped mountains overlooking the Bay. As the guest winds made us shiver the voyagers standing on the top deck of the Atlantic Ocean posed for pictures while many others lost in the stunning beauty created by Mother Nature for all of us to enjoy and cherish for ever.

The final landing on the Last Horizon on Friday December 6th afternoon wa sdcc at the Deception Island for the AAPI Votagers.

An unusually bright shi ing sky with gentle winds welcomed us to the shore of the black sandy with little stones spread all along the 36 kms wide island.

The volcanic eruption here over 50 years ago has turne DC the island the mountains into dark colored. Saw a huge deal on the shore resting with birds and few penguins of the Contindnt enjoying the mild weather, the voyagers trekked up.the hill on the dark sand while the panoramic and breath taking views on the snowy mountains beyond the Bay hovering over blue waters of the Last Horizon.

Each evening at cocktail hour the entire expedition community gathers in the lounge for a ritual we call Recap. As you enjoy cocktails and hors d’oeuvres, various naturalists give talks, the undersea specialist may show video, and your expedition leader will outline the following day’s schedule.

penguins. Gentoo, Adelie, chinstraps in the thousands; rockhopper, macaroni and king penguins in the Falklands; and king penguins at a staggering scale in South Georgia.

We were all excited about the sightings of a rare black and a rare white penguin, as well as a lone Emperor colony at our farthest south.

Penguin behavior is endlessly fascinating. In the Antarctic spring, hundreds of gentoo penguins parade before us, reestablishing their bonds, mating, staking their claims, and thievishly stealing stones from one another for their nests.

The photo ops are simply incredible. And while penguins are delightful in films and nature documentaries, watching the often-madcap business of penguin life being lived around you is simultaneously uplifting and humbling: the animal kingdom indeed.

The photo ops are simply incredible. And while penguins are delightful in films and nature documentaries, watching the often-madcap business of penguin life being lived around you is simultaneously uplifting and humbling: the animal kingdom indeed.

We’ll find it resting on ice floes, and often will have the opportunity to approach closely in Zodiacs for excellent photo ops. We’ll also likely be able to observe Weddell and crabeater seals, as well as Antarctic fur seals, whose populations have rebounded since the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and the 1972 Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals.

Antarctic birds

See Arctic terns and other pelagic birds, including fulmars and petrels. The opportunity of a lifetime for bird lovers, however, lies in venturing further—into the lands of the albatross,

The beautiful black-browed albatross crowd the ledges

The wandering albatross, with the largest wingspan of any bird, is one of the many wildlife spectacles South Georgia affords.

We woke up sailing on choppy seas with northerly winds of 45 knots.

When we reached the western side of the island, we found ourselves at the top of the spectacular colony of rockhopper penguins, and black-browed albatross. Brown skuas flew over the colony while penguins, albatross, and shags took care of their eggs.

We spend a good bit of time photographing the birds and generally taking in such wonderful experience and close views of the wildlife.

Settling into the calm waters of Cierva Cove, we headed out for a morning of Zodiac cruising. As the ship disappeared behind us in the mist, we hugged the shoreline to enjoy views of the Argentine research station Base Primavera, rolling swell around dramatic icebergs, and an undisturbed colony of gentoo penguins going about their usual Sunday morning business.

Highlights of the morning included great sightings of Weddell seals snoozing on ice and swimming curiously in the turquoise waters. As the fog began to lift, dramatic mountain peaks showed through the clouds and we were treated to stunning views of the surrounding glaciers and impressive icebergs throughout the cove.

Dramatic sculpture-like structures made for fantastic photo opportunities, and it was tough to return in time for lunch from such a beautiful morning out on the water.

Before long, we lost count of the number of emperor penguins we laid our eyes on. Cut loose upon the sea ice, our guests took to skiing and snowshoeing to explore the icy landscape and spend time with a gaggle of the largest penguin species on our unique planet.

Today, Antarctica is certainly one of the ultimate tour destinations of the world. However, for more than 150 years after its discovery, Antarctica was too far, too remote, too extreme, too dangerous, and too expensive for all but the most stout-hearted explorers and adventurers.

Those people willing to risk everything for the tasks at hand and fortunate enough to have the financial backing of governments or wealthy organizations. Few simple travelers could dare venture into this domain. To go there meant outfitting an expedition, and necessitated making preparations for all kinds of contingencies.

Those people willing to risk everything for the tasks at hand and fortunate enough to have the financial backing of governments or wealthy organizations. Few simple travelers could dare venture into this domain. To go there meant outfitting an expedition, and necessitated making preparations for all kinds of contingencies.

The human history of Antarctica contains some of the most exciting stories of endeavor and persistence imaginable, and includes many survival tales of people overcoming almost unimaginable odds. It is also wrought with many heart-wrenching tragedies.

But, whatever their reasons for going to Antarctica, these people were first and foremost adventurers at heart. It has taken the efforts of these many expeditions and fearless explorers to reduce much of the Antarctic mystery and danger.

The ship could carry 92 passengers along with about 60 crew members, naturalists, and lecturers.

inflatable boats called Zodiacs provided the means for his passengers to get ashore almost anywhere, under a multitude of conditions.

There are two major types of ice in the polar regions, sea ice and glacial ice, and they form through different methods. Sea ice forms in oceanic water when the ambient temperature is lowered to the freezing point of salt water. Glacial ice (including ice caps) forms through the simple accumulation of snow which becomes compressed by its own weight into solid ice. Sea ice formation is a seasonal phenomenon (although individual pieces of sea ice may last for several years), while glacial ice is generally a long-term structure lasting decades, centuries, or even millennia.

If conditions are calm, the crystals join together, thicken, and form a fibrous structure called young ice.

If conditions are calm, the crystals join together, thicken, and form a fibrous structure called young ice.

Sea ice prevents the ocean waters from warming the coasts significantly. It is important to note that islands within the limits of Winter pack ice (such as the South Shetlands, South Orkneys, etc.) compare closely with the continent in seasonal temperatures, soils types, flora, and fauna.

Glaciation, however, is much more complicated. When snow accumulates over a period of many years (that is, it doesn’t melt away after one season), the buildup creates a thick deposit in which the overlying mass tends to compress the lower snow layers into solid ice. During this, the individual snowflakes change into granules, which fuse into crystals of ice. Often, the air between the flakes becomes trapped, thereby creating air bubbles within the ice crystals. In polar areas, this produces huge and massive ice caps that can overwhelm and cover the entire landscape, including even mountains. Eventually, the ice mass thickens to the point where it begins to move due to a combination of gravity and the shape and slope of the ground surface. On steeper slopes this can occur when the thickness of the combined snow and ice reaches 15 m (50 feet) in depth. This is often referred to as glacial ice. If the flowing ice is constrained by mountains, valley walls, or other land surface formations, it is known as a glacier.

Glacial ice is the world’s largest reservoir of fresh water, albeit in solid form. Nearly 99% of all glacial ice on Earth is contained within the huge ice sheets in the polar regions. In fact, this volume of ice is so large that if the ice sheets of both Greenland and Antarctica were to melt, it would cause sea levels to rise about 70 meters (230 ft). In addition to Antarctica, Greenland, Canada, Iceland, and Svalbard, there are also significant glaciers scattered around the world outside of polar regions, including Alaska and Chilean Patagonia.

Permanent ice probably began forming in Antarctica as early as Miocene times, perhaps 20 million years ago.

There are 17 species of penguins in the world and they have various qualities in common. They are all found in the southern hemisphere, although one species, the Galapagos penguin, actually ranges a few miles north of the equator. Penguins are the most aquatic of the sea birds, and they generally spend most of their lives at sea (except when molting or rearing young). All penguins are flightless and adapted for life in cold water, so even those found in the low latitudes are dependent upon cold water currents for their livelihood.

There are 17 species of penguins in the world and they have various qualities in common. They are all found in the southern hemisphere, although one species, the Galapagos penguin, actually ranges a few miles north of the equator. Penguins are the most aquatic of the sea birds, and they generally spend most of their lives at sea (except when molting or rearing young). All penguins are flightless and adapted for life in cold water, so even those found in the low latitudes are dependent upon cold water currents for their livelihood.

Except for the feet and perhaps bare patches on the face, the entire body is covered with small, dense, overlapping, scale-like feathers, and there is a downy tuft at the base of each feather which increases the heat retention abilities even more. Feathers account for about 80% of the penguins’ insulative properties, while fat provides the other 20%. Penguins have very high internal body temperatures (about 38° C, or 101° F), as well as high metabolic rates. With all this taken into account it is easy to understand how the Antarctic species in particular can survive, and even thrive, in a cold, harsh climate.

Around the Antarctic Peninsula, we commonly see gentoo (Pygoscelis papua), Adélie (Pygoscelis adeliae), chinstrap (Pygoscelis Antarctica), emperor (Aptenodytes forsteri), and rarely Macaroni (Eudyptes chrysolophus) penguins.

On South Georgia, we can see king (A. patagonica), gentoo (P. papua), chinstrap (P. Antarctica), and Macaroni (Eudyptes chrysolophus) penguins.

Whales (this term applies to all whales, dolphins, porpoises, etc.) are air breathing mammals, but have perfected the ability to live entirely in water over the past 50 to 60 million years.

On the Ship, immediately after settling down in each one’s cabin, the voyagers were invited to learn about safety on the ship and participated in a safety drill. Shelli Ogilvy, the Veteran Expedition Leader introduced the 22 Expedition Members with extensive maritime experiences from around the world, and over 60 other crew members to the voyagers.

On the Ship, immediately after settling down in each one’s cabin, the voyagers were invited to learn about safety on the ship and participated in a safety drill. Shelli Ogilvy, the Veteran Expedition Leader introduced the 22 Expedition Members with extensive maritime experiences from around the world, and over 60 other crew members to the voyagers. After sailing across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans and through the turbulent Drake Passage, and the South Ocean, finally, the day arrived for the Voyagers. The one they had been eagerly waiting for. On December 3rd, our ship, the Ocean Atlantic anchored on Danco Island, off the coast of the 7th Continent, Antarctica, officially discovered in 1820, although there is some controversy as to who sighted it first

After sailing across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans and through the turbulent Drake Passage, and the South Ocean, finally, the day arrived for the Voyagers. The one they had been eagerly waiting for. On December 3rd, our ship, the Ocean Atlantic anchored on Danco Island, off the coast of the 7th Continent, Antarctica, officially discovered in 1820, although there is some controversy as to who sighted it first In the afternoon, after lunch and a lecture on the history of Antarctica, the Ocean Atlantic ship, travelling about 25 nautical miles, for the first time ever, landed on the Antarctic Continent as she reached the shores of Paradise Bay, a beautiful island, where the famous Brown Center, the Argentinian Research Station was located.

In the afternoon, after lunch and a lecture on the history of Antarctica, the Ocean Atlantic ship, travelling about 25 nautical miles, for the first time ever, landed on the Antarctic Continent as she reached the shores of Paradise Bay, a beautiful island, where the famous Brown Center, the Argentinian Research Station was located. Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay.

Immediately after breakfast we set out in small groups of ten on each Zodiac to cruise on the pristine blue waters of the Lamoy Bay. Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top. For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters.

For the first time we were delighted to watch different kinds of Penguins sitting on a single rock glazing at the ocean waters. Today, on December 4th, the voyagers got onto the Zodiacs and sailed to Port Lockroy, a sheltered harbor with a secure anchorage and the Antarctic Peninsula since its discovery in 1904. The Port also is home to a Museum and a British Post Office, where the early visitors to the Continent lived and explored the wildlife of the last Horizon. The Museum has preserved the antiques used by the early voyagers, which is an important role in the history of Antarctica.

Today, on December 4th, the voyagers got onto the Zodiacs and sailed to Port Lockroy, a sheltered harbor with a secure anchorage and the Antarctic Peninsula since its discovery in 1904. The Port also is home to a Museum and a British Post Office, where the early visitors to the Continent lived and explored the wildlife of the last Horizon. The Museum has preserved the antiques used by the early voyagers, which is an important role in the history of Antarctica. Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top. Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Colonies of penguins in smaller groups greeted us with their enchanting voices. We watched in awe as tiny penguins walking up flapping their feathers occasionally from the bottom of the hill to the top. The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent.

The bright sun and the gentle breeze embracing the cheeks of the voyagers it was a perfect day to cruise and explore the White Continent. The photo ops are simply incredible. And while penguins are delightful in films and nature documentaries, watching the often-madcap business of penguin life being lived around you is simultaneously uplifting and humbling: the animal kingdom indeed.

The photo ops are simply incredible. And while penguins are delightful in films and nature documentaries, watching the often-madcap business of penguin life being lived around you is simultaneously uplifting and humbling: the animal kingdom indeed. Those people willing to risk everything for the tasks at hand and fortunate enough to have the financial backing of governments or wealthy organizations. Few simple travelers could dare venture into this domain. To go there meant outfitting an expedition, and necessitated making preparations for all kinds of contingencies.

Those people willing to risk everything for the tasks at hand and fortunate enough to have the financial backing of governments or wealthy organizations. Few simple travelers could dare venture into this domain. To go there meant outfitting an expedition, and necessitated making preparations for all kinds of contingencies. If conditions are calm, the crystals join together, thicken, and form a fibrous structure called young ice.

If conditions are calm, the crystals join together, thicken, and form a fibrous structure called young ice. There are 17 species of penguins in the world and they have various qualities in common. They are all found in the southern hemisphere, although one species, the Galapagos penguin, actually ranges a few miles north of the equator. Penguins are the most aquatic of the sea birds, and they generally spend most of their lives at sea (except when molting or rearing young). All penguins are flightless and adapted for life in cold water, so even those found in the low latitudes are dependent upon cold water currents for their livelihood.

There are 17 species of penguins in the world and they have various qualities in common. They are all found in the southern hemisphere, although one species, the Galapagos penguin, actually ranges a few miles north of the equator. Penguins are the most aquatic of the sea birds, and they generally spend most of their lives at sea (except when molting or rearing young). All penguins are flightless and adapted for life in cold water, so even those found in the low latitudes are dependent upon cold water currents for their livelihood.

She won everyone’s hearts with her sartorial choice at the event as she marked her presence in the same saree that she wore during her wedding ceremony with Ranbir. She styled the saree in a

She won everyone’s hearts with her sartorial choice at the event as she marked her presence in the same saree that she wore during her wedding ceremony with Ranbir. She styled the saree in a

Today, Suntory’s water sanctuary project spans roughly 12,000 hectares in 22 locations across 15 prefectures in Japan, replenishing more than twice the water consumed by Suntory’s plants.

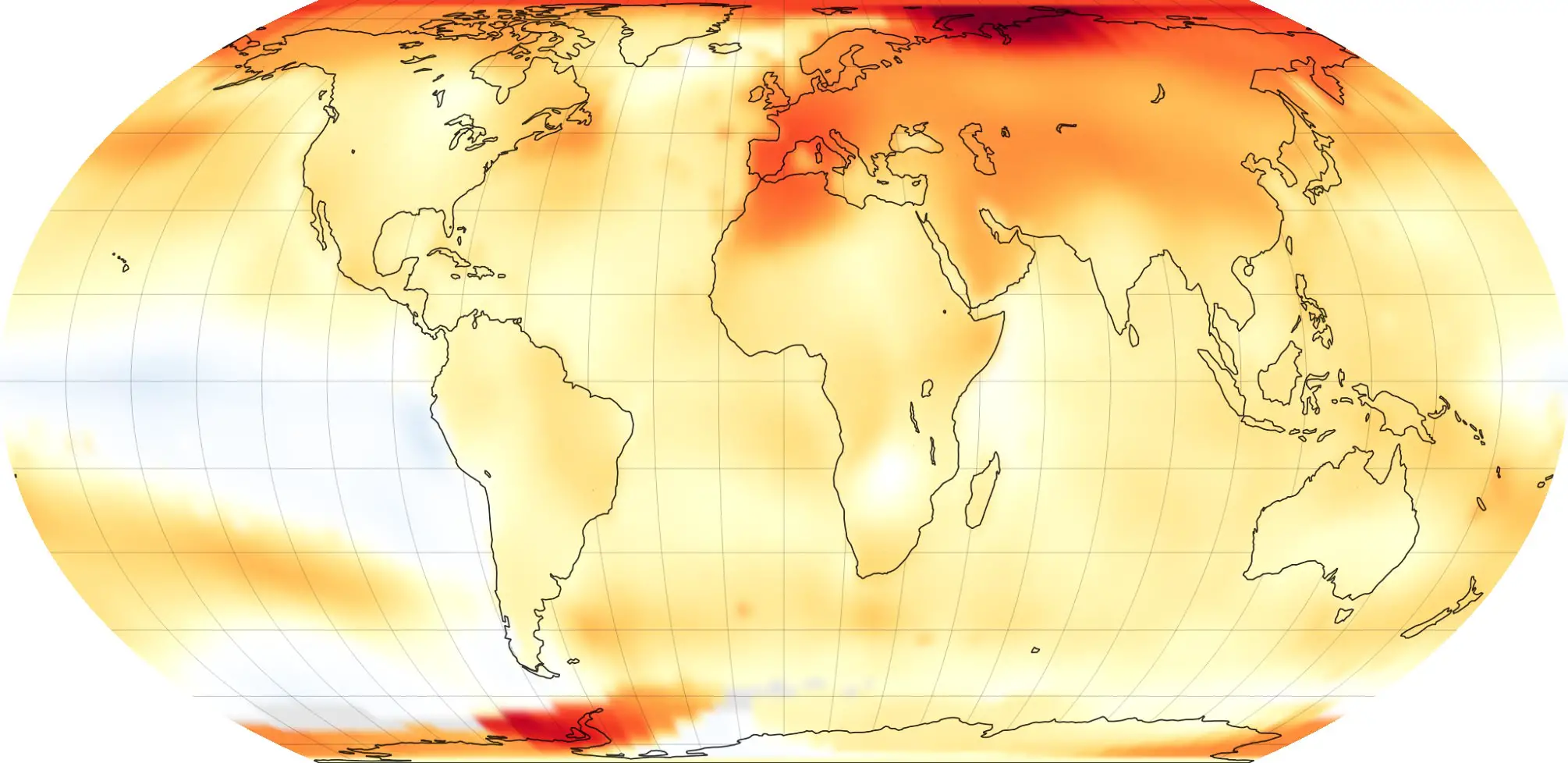

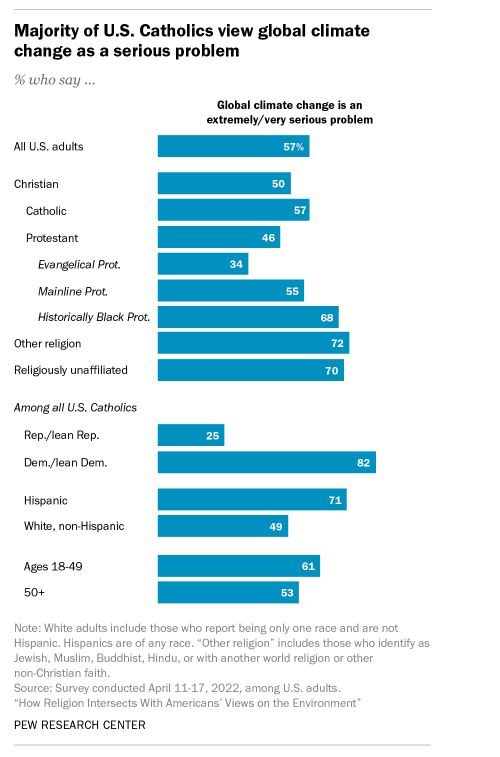

Today, Suntory’s water sanctuary project spans roughly 12,000 hectares in 22 locations across 15 prefectures in Japan, replenishing more than twice the water consumed by Suntory’s plants. Laudate Deum’s extensive explanation of the latest climate science garners praise from climate scientists. Carmelite Fr. Eduardo Agosta Scarel, a climate scientist and senior adviser to the Laudato Si’ Movement, applauds the document’s use of up-to-date scientific knowledge. However, he points out a concern with the Pope’s use of the term “correlation” when describing the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. He emphasizes that it’s not merely a correlation but a well-established scientific theory explaining the Earth’s climate behavior.

Laudate Deum’s extensive explanation of the latest climate science garners praise from climate scientists. Carmelite Fr. Eduardo Agosta Scarel, a climate scientist and senior adviser to the Laudato Si’ Movement, applauds the document’s use of up-to-date scientific knowledge. However, he points out a concern with the Pope’s use of the term “correlation” when describing the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. He emphasizes that it’s not merely a correlation but a well-established scientific theory explaining the Earth’s climate behavior. January:As the new year begins, the southern U.S. might experience slightly colder-than-average temperatures. A typical feature of El Niño is cool and wet conditions in parts of the southern states during the heart of winter, and this outlook suggests that from the Southern Plains to Georgia and the Carolinas, there’s a possibility of increased chances for snow and ice. On the other hand, parts of the Northwest and Northeast have the highest likelihood of experiencing above-average temperatures in January.

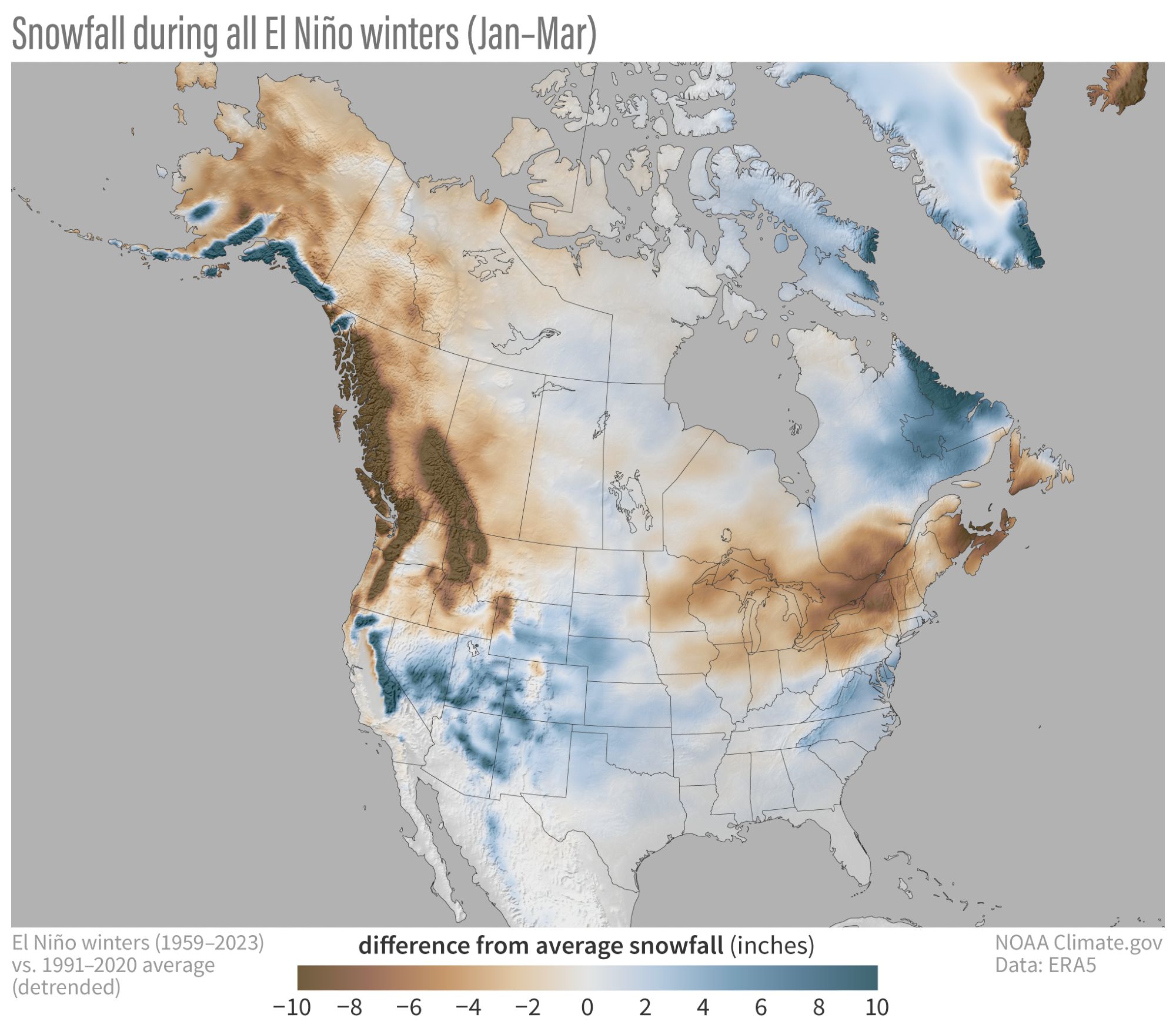

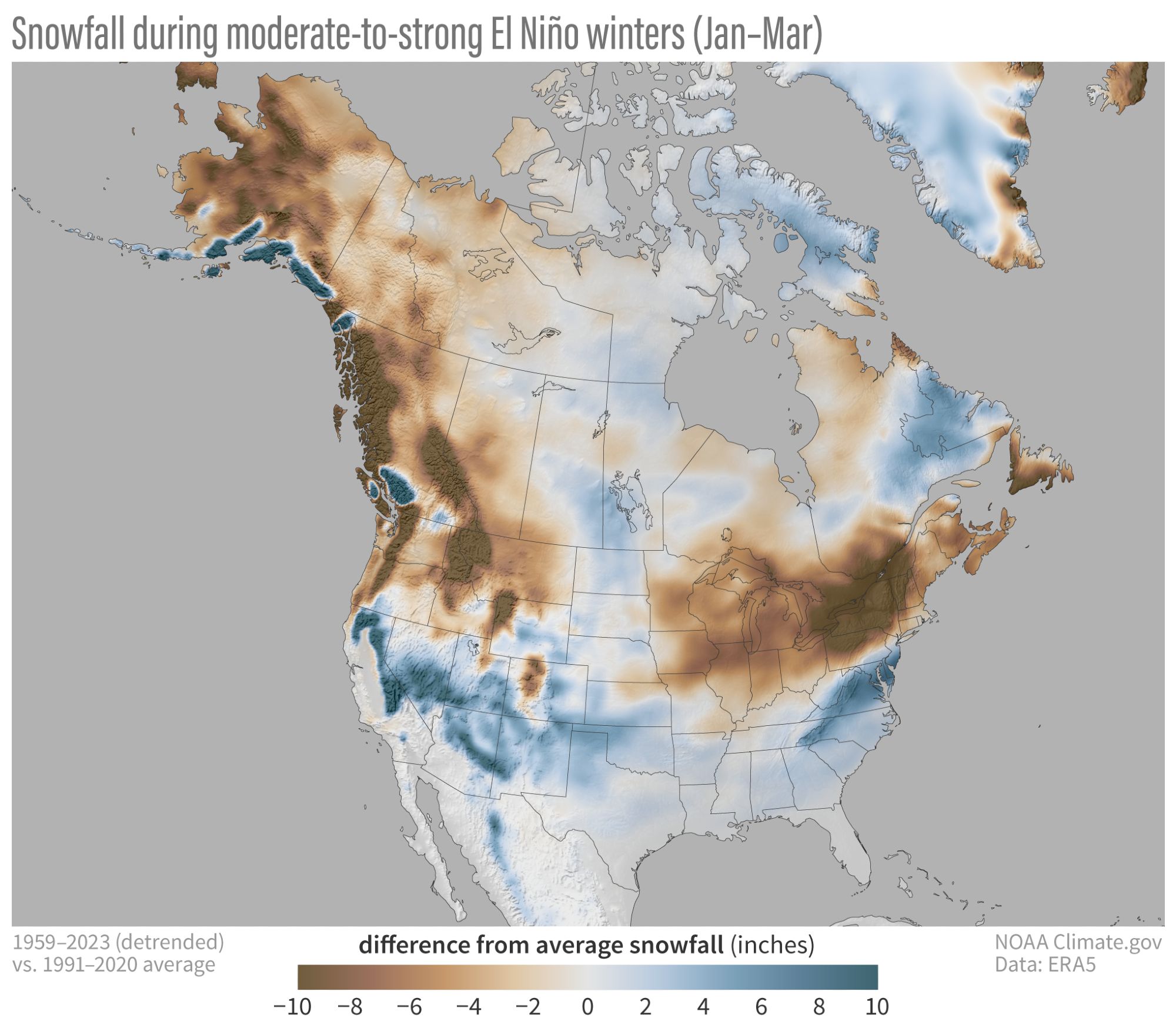

January:As the new year begins, the southern U.S. might experience slightly colder-than-average temperatures. A typical feature of El Niño is cool and wet conditions in parts of the southern states during the heart of winter, and this outlook suggests that from the Southern Plains to Georgia and the Carolinas, there’s a possibility of increased chances for snow and ice. On the other hand, parts of the Northwest and Northeast have the highest likelihood of experiencing above-average temperatures in January. India, in its approach, intends to persist in resisting the pressure from developed economies to establish a concrete deadline for phasing down the use of fossil fuels. Instead, it is advocating for a shift in focus towards reducing overall carbon emissions through the use of “abatement and mitigation technologies.” These insights were provided by the two officials, and a third government official, who opted to remain anonymous as these discussions are confidential, and a definitive stance has not yet been established.

India, in its approach, intends to persist in resisting the pressure from developed economies to establish a concrete deadline for phasing down the use of fossil fuels. Instead, it is advocating for a shift in focus towards reducing overall carbon emissions through the use of “abatement and mitigation technologies.” These insights were provided by the two officials, and a third government official, who opted to remain anonymous as these discussions are confidential, and a definitive stance has not yet been established.