The Atlantic hurricane season commences on June 1, with meteorologists closely monitoring increasing ocean temperatures – not just in the Atlantic, but around the world. In the spring of 2023, global sea surface temperatures capable of energizing hurricanes have reached unprecedented levels. However, for Atlantic hurricanes, the crucial ocean temperatures lie in two regions: the North Atlantic basin, where hurricanes originate and intensify, and the eastern-central tropical Pacific Ocean, the birthplace of El Niño.

This year, these two factors seem to be at odds, potentially leading to opposing impacts on the vital conditions that determine the outcome of an Atlantic hurricane season. Consequently, this could spell positive news for the Caribbean and Atlantic coasts with a near-average hurricane season in store. Nonetheless, meteorologists caution that this hurricane forecast is contingent upon the development of El Niño.

The makings of a hurricane

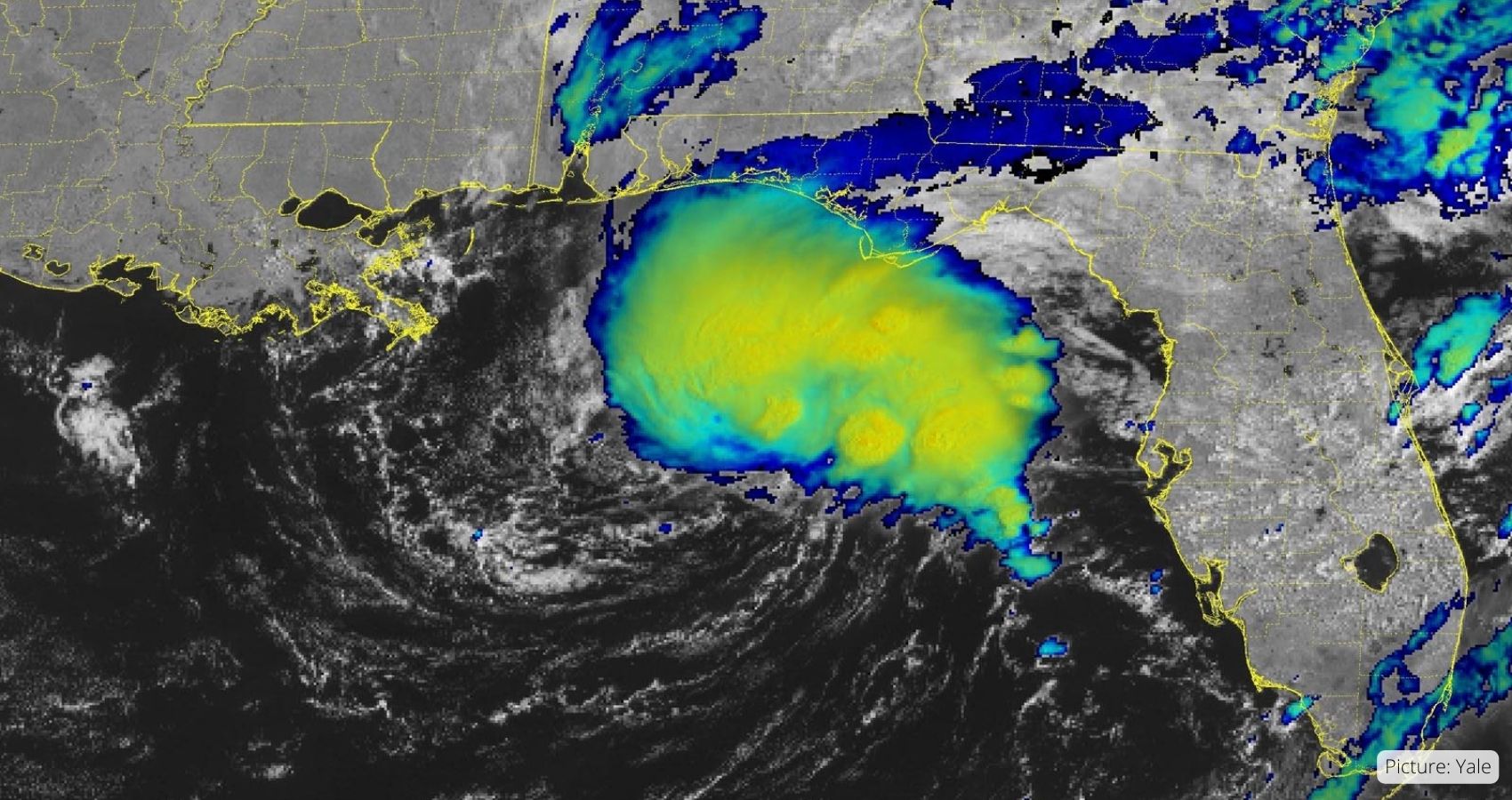

Generally, hurricanes are more likely to form and strengthen when a tropical low-pressure system comes across an environment with warm upper-ocean temperatures, atmospheric moisture, instability, and minimal vertical wind shear. Warm ocean temperatures fuel hurricane development, while vertical wind shear – the difference in strength and direction of winds between the lower and upper parts of a tropical storm – disrupts convection organization (thunderstorms) and introduces dry air into the storm, hindering its growth.

The Atlantic Ocean’s contribution

The Atlantic Ocean’s role is relatively simple. Hurricanes extract energy from the warm ocean water beneath them. The warmer the ocean temperatures, the more favorable conditions are for hurricanes, assuming all other factors remain equal. Tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures were exceptionally high during the most active Atlantic hurricane seasons in recent history. The 2020 season saw a record 30 named tropical cyclones, and the 2005 season produced 28 named storms, with 15 becoming hurricanes, including Hurricane Katrina.

The Pacific Ocean’s involvement

The tropical Pacific Ocean’s role in Atlantic hurricane formation is more complex. One may wonder how ocean temperatures on the opposite side of the Americas can impact Atlantic hurricanes. The answer lies in teleconnections – a series of processes where a change in the ocean or atmosphere in one region leads to large-scale alterations in atmospheric circulation and temperature, influencing weather elsewhere. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation is a recurring pattern of tropical Pacific climate variability that initiates teleconnections.

When the tropical eastern-central Pacific Ocean is unusually warm, El Niño can form. During El Niño events, warm upper-ocean temperatures alter vertical and east-west atmospheric circulation in the tropics, initiating a teleconnection that affects east-west winds in the upper atmosphere throughout the tropics, ultimately resulting in stronger vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin. This wind shear can suppress hurricanes.

Forecasters expect this to occur in the upcoming summer, with a 90% likelihood of El Niño developing by August and remaining strong throughout the fall peak of the hurricane season.

A tug-of-war between Atlantic and Pacific influences

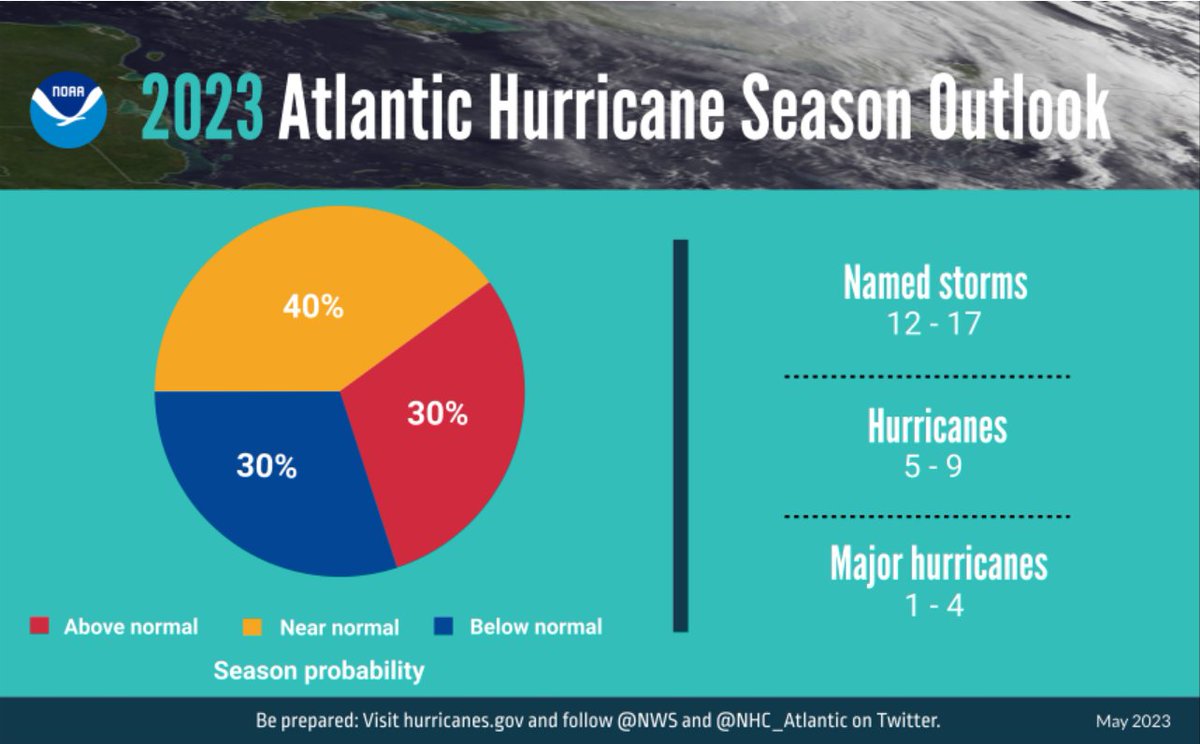

Research by atmospheric scientists, including my own, has shown that a warm Atlantic and a warm tropical Pacific tend to counteract each other, resulting in near-average Atlantic hurricane seasons. Both observations and climate model simulations support this outcome. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 2023 forecast predicts a near-average season with 12-17 named storms, 5-9 hurricanes, and 1-4 major hurricanes. An earlier outlook from Colorado State University forecasters anticipates a slightly below-average season, with 13 named storms compared to a climatological average of 14.4.

Wild cards to consider

While tropical Atlantic and Pacific Ocean temperatures often contribute to accurate seasonal hurricane forecasts, other factors should be considered and monitored. First, will the predicted El Niño and Atlantic warming occur? If one or both do not, it could tip the balance in the tug-of-war between influences. The Atlantic Coast should hope for El Niño to develop as forecasted, as such events often decrease hurricane impacts in the region. If this year’s anticipated Atlantic Ocean warming were paired with La Niña – El Niño’s opposite, characterized by cooler tropical Pacific waters – it could potentially lead to a record-breaking active season.

Two additional factors are also crucial: the Madden-Julian Oscillation, a pattern of clouds and rainfall that moves eastward through the tropics on a 30-90 day timescale and can either promote or suppress tropical storm formation, and dust storms from the Saharan air layer, which contains warm, dry, and dusty air from Africa that can inhibit tropical cyclones.