In an era dominated by consumerism, the essence of love is often overshadowed by commercial expectations, yet true love thrives in quiet actions and genuine presence.

Love is one of the most exalted, mysterious, and contested human experiences. Across centuries, poets, philosophers, mystics, and artists have attempted to define it, yet its deepest meaning often eludes final articulation. In contemporary society, commerce has learned to package and sell a facsimile of love, evident in the proliferation of Valentine’s Day gifts, Christmas promotions, and other glittering seasons of “must-buy” tokens that claim to represent devotion.

The National Retail Federation projects that Valentine’s Day spending in the U.S. will reach a record $29.1 billion this year, serving as a stark reminder that love’s loudest public rituals frequently hinge on consumer spending. Each February, retail channels overflow with roses, chocolates, jewelry, and obligatory “proofs” of love. The underlying message is familiar: if you don’t buy, you don’t care enough. Over time, this ritual can shift from nurturing relationships to fulfilling market-driven expectations.

I propose a counter-vision: true love is quiet, soulful, and deeply ethical—expressed through thoughtfulness and action rather than grand declarations or material purchases. To invert a famous movie line, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry,” we might say: love means rarely having to say “I love you,” because its presence is evident without constant verbal affirmation.

This vision of love stems from a broader philosophy of stewardship. I prefer to invest my resources in creating lasting memories and meaningful experiences that deepen over time, rather than in material possessions whose novelty is destined to fade.

For over fifty years of marriage, my wife and I have exercised a quiet control over our resources, valuing the freedom to determine when, how, and why we honor our bond, independent of marketplace dictates. We reached an understanding early in our relationship: we do not need a designated day in February to shop for tokens of love simply because a marketing calendar demands it. Our bond flourishes on a quiet fidelity grounded in actions and presence.

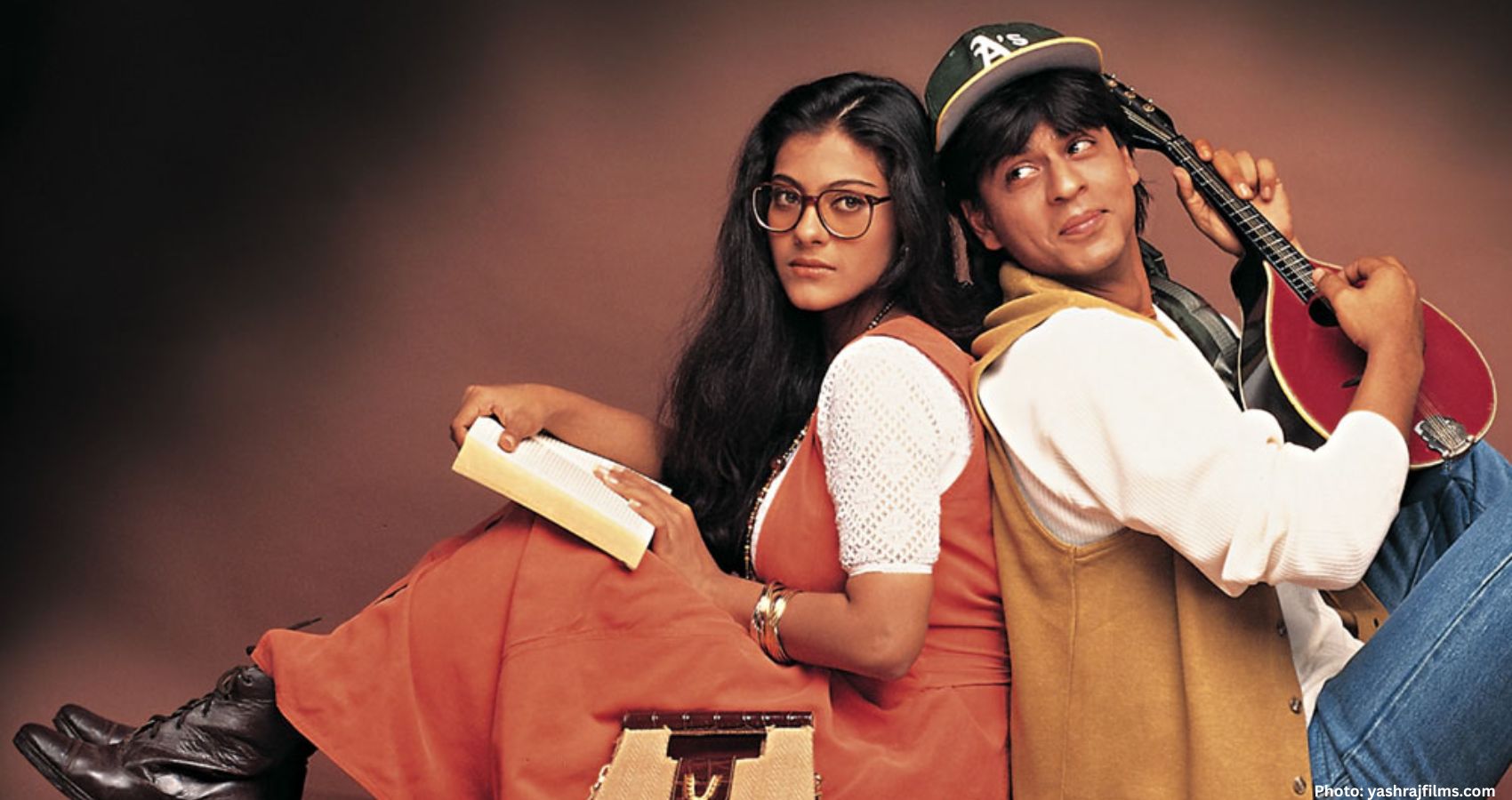

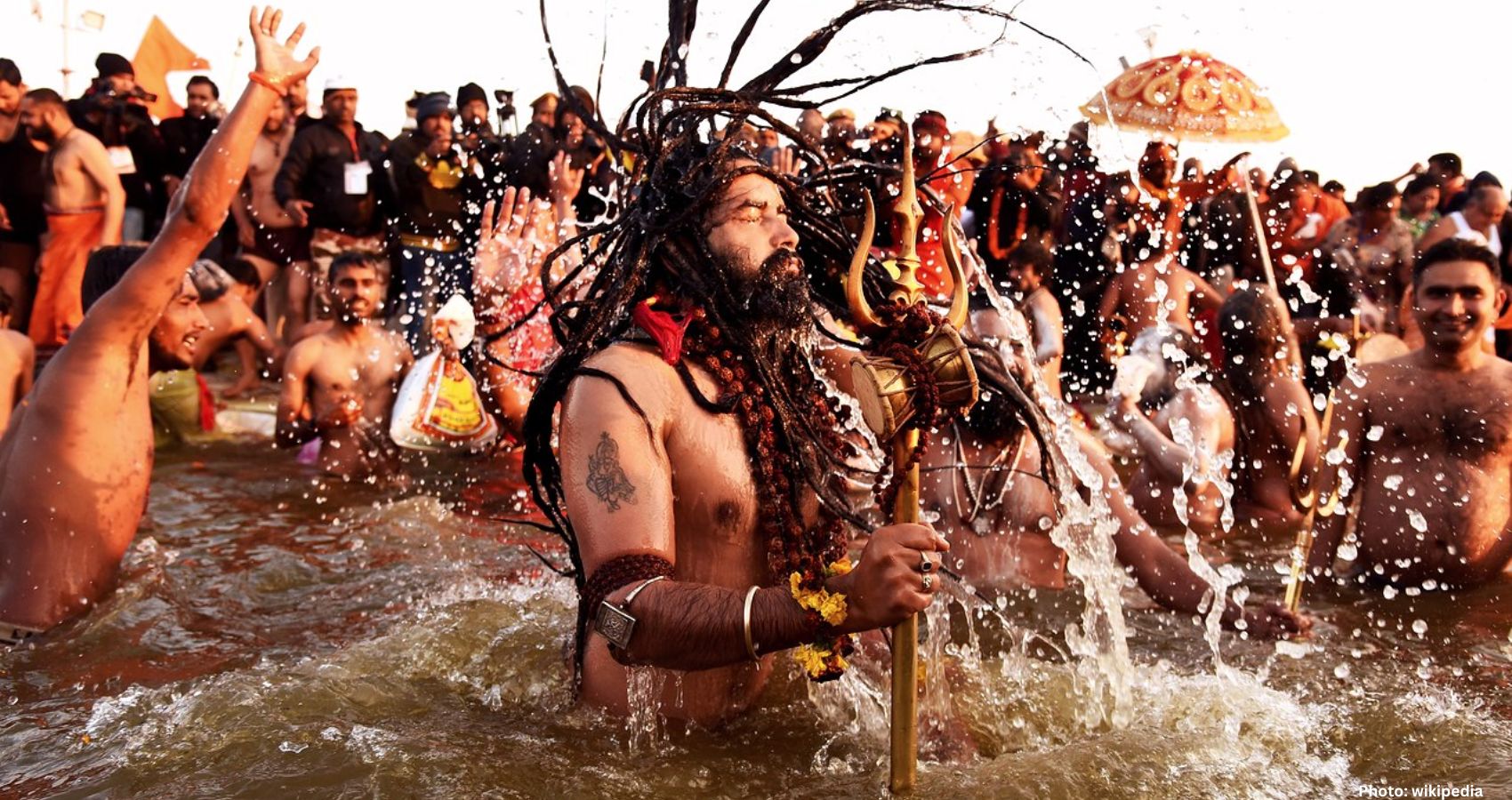

As a touchstone, I turn to the song “Hamne dekhi hai un aankhon ki mehekti khushboo” from the Hindi film *Khamoshi* (1969/1970)—a piece that transcends cliché and gestures toward a love that is spiritual, inward, and nameless. By contrasting this luminous, inward vision with the commercialization of love in consumer culture, we can reclaim a deeper understanding of what it means to love—and to be loved.

True love often manifests as a quiet presence. It is less about the refrain “I love you” and more about the steadiness of showing up; less about spectacle and more about fidelity. Across various mystical traditions—Sufi, Bhakti, contemplative Christianity—love is a union at the level of the soul, a current felt beneath words. When love matures, it seeks no constant validation; its native language is attentiveness: an unhurried hand on the shoulder, shared silence that offers safety, listening that is not a prelude to rebuttal. Words become optional because the ethic of presence has already spoken.

Psychology complements this intuition. Attachment theory, applied to adult romantic relationships, describes love as a secure base that supports exploration and growth, echoing the “quiet presence” motif.

In his Triangular Theory of Love, American psychologist Robert J. Sternberg posits that enduring love integrates intimacy (closeness), passion (vitality), and commitment (pledge)—all quiet strengths rather than constant performance.

True love does not keep ledgers. It does not convert affection into a running account of debts and credits. At its best, love is other-regarding—seeking the beloved’s flourishing even when applause is absent and reciprocity delayed. Research on adult attachment reveals that secure bonds reduce defensive accounting and invite generosity in care.

We believe in actions because they endure under pressure. A hundred small deeds—patience during a partner’s low season, quiet advocacy in a friend’s crisis, steadiness when life becomes challenging—speak volumes more than slogans. This aligns with findings that gratitude and prosocial behavior enhance relationship well-being and satisfaction; material tokens alone are poor substitutes.

Specific roles, such as boyfriend, girlfriend, or spouse, help society organize life, but the experience of love often transcends these labels. Love’s deeper signature is formless: an undercurrent that persists through changing roles, labels, and seasons. This is why the right metaphor often feels like fragrance rather than a contract—something sensed more than stated.

The commercialization of love each February tends to be transactional (spend to receive), seasonal, and conditional (the “right” gift becomes a moral test). These dynamics can flatten love into mere exchange, reducing its true meaning. For many—especially those on tight budgets—the pressure to prove love materially can lead to anxiety. Marketing scripts suggest that love must be performed through purchases; failure to do so implies emotional failure.

Yet research consistently links gratitude, presence, and prosocial acts with higher well-being than material accumulation.

True love lingers in the margins: small kindnesses, quiet sacrifices, and steady presence. Commercial love monopolizes center stage: spectacle, symbolism, and shareable performance.

Words can be nourishing—or numbing. Repetition can become a habit rather than a heartbeat. In secure bonds, love is embodied: someone rises early to ease your day, holds you when you falter, listens to what you cannot yet articulate. When the life of the relationship already conveys “I love you,” the phrase, while welcome, is not the essence.

True love reveals itself daily in actions we often take for granted or overlook: a caregiver wakes before dawn, no applause expected; a friend sits with you in grief, offering presence without advice; a partner ends a spiral with a gentle gesture, not a scorecard; a teacher focuses their attention on a struggling student, unnoticed by others; volunteers work tirelessly in disasters without seeking recognition or reward.

These acts illustrate a simple axiom: love thrives not as performance, but as quiet fidelity.

Presence over presents. Whenever possible, prioritize attention and time over material gifts.

Reject the guilt narrative. Don’t outsource your worth to a marketing calendar.

Practice silent acts. Perform unannounced kindnesses; allow love to surprise, not advertise.

Celebrate love daily. Love does not require an officially branded day; it exists in recurring, unphotographed rituals.

Cultivate inner awareness. As the song from *Khamoshi* advises, let love remain felt—not merely named.

When love is true, there is little need for words. It has already been expressed in the way you listen, the way you live, and in the small, unmarketable acts that commerce cannot replicate.

According to India Currents, the essence of love is found in actions and presence rather than in material expressions dictated by consumer culture.