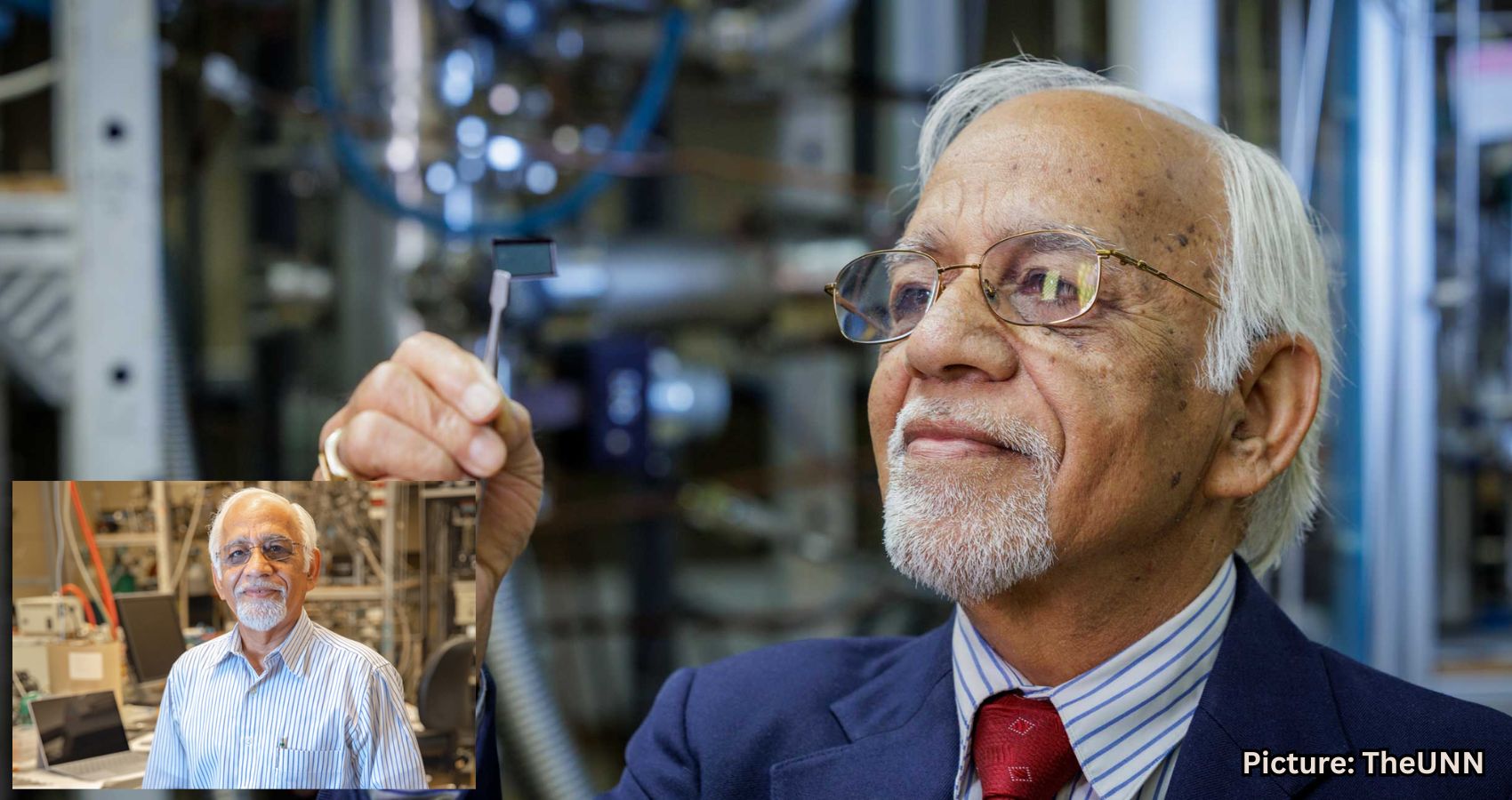

Dr. Raj Singh, a professor at Oklahoma State University, has been honored as the Big 12 Faculty of the Year for his significant contributions to materials science and engineering education.

Dr. Raj Singh, an Indian American professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at Oklahoma State University (OSU), has been named the Big 12 Faculty of the Year. This prestigious award recognizes one outstanding faculty member from each institution within the Big 12 Conference, which spans from Arizona to West Virginia. The honor is given to those who exemplify excellence in teaching, research, and academic leadership while promoting student success.

Singh, who holds the title of Regents Professor at OSU’s College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology (CEAT), was selected for this accolade due to his groundbreaking contributions to materials science and engineering research, as well as his enduring commitment to educating and mentoring future engineers.

“Dr. Singh’s work reflects the core of CEAT’s mission, advancing cutting-edge research while preparing students to solve real-world challenges,” stated Hanchen Huang, dean of CEAT. “His selection as Big 12 Faculty of the Year highlights the caliber of faculty at Oklahoma State University and the impact they have locally, nationally, and globally.”

Singh’s research has significantly influenced innovation across various industries, and his dedication to student learning and mentorship has played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of engineers and researchers. His recognition underscores CEAT’s leadership in engineering education and applied research within the Big 12 Conference.

“We are constantly looking for ways to highlight how Big 12 faculty continue to educate and inspire the next generation of leaders,” said Jenn Hunter, Chief Impact Officer of the Big 12. “From the arts and filmmaking to business and engineering, this year’s cohort showcases the vast opportunities available to students pursuing an education on Big 12 campuses.”

The award also reflects the extensive research excellence present across the conference, covering disciplines from astronomy and psychology to engineering and the arts. Singh joins a distinguished group of faculty members recognized this year, further enhancing the reputation of OSU and CEAT for academic excellence and innovation.

“I am surprised, delighted, humbled, and grateful to the selection committee and those responsible for their support for this most prestigious recognition and award,” Singh expressed upon receiving the honor.

Singh was the founding head of the School of Materials Science and Engineering at OSU–Tulsa. He earned his Doctor of Science degree in ceramics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and has held positions at Argonne National Laboratory, the GE Global Research Center, and the University of Cincinnati prior to joining OSU.

His research career encompasses numerous fields, including nanostructured materials, nanotubes and nanorods, fuel cell materials, smart ferroelectric materials, and ceramic matrix composites (CMCs). Singh has authored over 350 research articles and holds 29 granted patents, establishing himself as a world-renowned expert in CMCs.

Notably, Singh pioneered the patented melt-infiltration process for producing fully dense, net-shape, damage-tolerant silicon carbide fiber-reinforced CMCs. This innovative process has been widely commercialized by GE Aviation since 2016, leading to significant advancements in the aerospace industry.

The technology has accumulated over 40 million flight hours in LEAP engines used by Airbus, Boeing 737 and 777, and COMAC aircraft, marking the world’s first commercial jet engines to incorporate CMCs as structural turbine components. These advancements have contributed to reduced engine weight, improved efficiency, and lower CO₂ and NOx emissions, creating new multibillion-dollar industries and delivering substantial societal and economic benefits.

In 2024, Singh was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, one of the highest professional honors for engineers, in recognition of his lifetime contributions to materials science and engineering.

Beyond his research accomplishments, Singh is deeply committed to educating and mentoring students. He views mentorship as a cornerstone of his role, helping students cultivate curiosity, creativity, and a lifelong passion for learning. His influence extends well beyond the laboratory, shaping the future of the engineering profession.

“The best part of my job is to help educate the best possible engineers and impart knowledge of the discipline of materials science and engineering,” Singh remarked. “I want to encourage students in the engineering field to be curious, persevering, creative, inventive, and passionate about their field. Never forget to be curious and inventive. It should be a lifelong pursuit.”

This recognition of Dr. Raj Singh not only highlights his individual achievements but also reflects the broader commitment of Oklahoma State University to excellence in education and research.

According to The American Bazaar.