CMEs, AI in Medicine, Health & Wellbeing, Women’s Forum, CEO Forum, Bollywood Extravaganza, Medical Research and Jeopardy Fill AAPI’s 43rd Annual Convention in Cincinnati, OH

Cincinnati, OH – July 27th: A historic moment unfolded as Dr. Amit Chakrabarty and Dr. Hetal Gor formally assumed charge as the President and the Chair, BOT respectively of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI) during the 43rd annual convention at the iconic Cincinnati Marriott at RiverCenter and Northern Kentucky Convention Center, Cincinnati, OH on Saturday, July 26th, 2025 as the convention came to a close with the gala attended by over 1,000 delegates from across the nation.

During a solemn ceremony Dr. Satheesh Kathula, the outgoing President of AAPI, passed on the gavel to Dr. Amit Chakrabarty during the Gala on Saturday night at the end of the convention, marking a new chapter of service, collaboration, and vision. The event brought together hundreds of members of AAPI, past leaders, and incoming officers, symbolizing unity and a shared commitment to elevating the voice of Indian-origin physicians across the U.S.

Along with Dr. Amit Chakrabarty, his executive committee consisting of Dr. Meher Medavaram, President-Elect; Dr. Krishan Kumar, Vice President; Dr. Seema Arora, Secretary; and Dr. Soumya Neravetla, Treasurer, assumed charge as part of the new Executive Committee. Dr. Hetal Gor assumed charge as the Chair, BOT. Dr. Gautam Kamthan will serve as the President, YPS, and Dr. Priyanka Kolli is the President, MSRF, both, representing the Medical Students and Fellows at the national AAPI.

“Today marks a sacred beginning—one that’s not only about taking oath, but about embracing purpose,” said Dr. Chakrabarty, immediately after taking charge as the President of AAPI, the nation’s largest ethnic medical association. “This stage is illuminated not just by lights, but by the commitment of every physician who’s journeyed with faith, resilience, and passion. With this new chapter, we honor our heritage, step forward with courage, and vow to lead with integrity.”

“I am committed to unify AAPI by breaking down the barriers of various regions, languages, medical education within the organization and bringing everyone together as a whole organization rather than separate fragments of the organization,” Dr. Chakrabarty said.

Dr. Chakrabarty rose through the ranks of AAPI with his hard work and dedication, serving AAPI for nearly a quarter century. “We have the potential to make a significant impact on the healthcare landscape of this country,” Dr. Chakrabarty asserted. “My goal this year is to unify AAPI by transcending the regional divides that have hindered our progress in recent years. Indian American physicians represent tremendous talent and potential, and the key to realizing that lies in collective action and a united voice—something I am committed to fostering.”

As he steps into this leadership role, Dr. Chakrabarty pledged to work toward strengthening and expanding AAPI, which represents the interests of over 120,000 Indian American physicians, Residents, and Fellows. The Alabama-based urologist envisions a future where AAPI becomes “more vibrant, united, transparent, and politically active,” with increased membership and a stronger presence among younger physicians. He emphasized the importance of ensuring that “AAPI’s voice is heard in the corridors of power.”

He underscored transparency with regular Townhall meetings with members and direct accessibility to answer any questions that the members have, providing a platform to answer any concerns, where elected BOT/EC members will present their findings based on a rational, non-biased, and objective review that will be communicated with the members and posted on the AAPI website.

Working with his dedicated executive committee, Dr. Chakrabarty wants that “our voices must be heard by the people making the laws. AAPI must succeed in bringing to the forefront the many important health care issues facing the physician community and raising our voice unitedly before the US lawmakers. Our membership is our strength; as the 2nd largest medical association behind the AMA, we cannot stay silent any longer,” he said.

In his warm farewell address, Dr. Kathula shared with the audience the many programs and initiatives he and his executive committee have organized in the past year since assuming charge as the President of AAPI. Dr. Kathula, among others, highlighted the successful organization of Global health Summit in New Delhi and Hyderabad, and the many initiatives at the Summit, research contest and the many charitable works and the webinars and workshops, as wells the Bone Marrow and Share a Blanket initiatives..

Dr. Kathula presented Presidential Awards to: Dr. Bhushan Pandya, Dr. Sunil Kaza, Dr. Vemuri Murthy, and Dr. Dwarkanda Reddy for their accomplishments and contribution to AAPI and to the larger society. Dr. Satheesh Kathula was honored for his outstanding leadership, commitment to AAPI’s mission, and for carrying the entire AAPI family together, as well as for his contributions to realize the lofty goals of AAPI.

“The organizing committees have been working hard to make the AAPI Convention of 2025 rewarding and memorable for all. They have been working hard to put together an attractive program for our annual get together, educational activities, and family enjoyment. We are fortunate to have a dedicated team of convention committee members from the Ohio region helping us,” Dr. Kathula said. He particularly called out Vijaya Kodali, for her dedication, integrity, and hard work as she manages AAPI office and coordinates the activities related to AAPI functioning.

At the BOT luncheon, physicians with distinguished achievements and community services were honored. Dr. Navin Nanda, Dr. P K Vedantham, Dr. Krishan Kumar, Dr. Jagdish Gupta, Dr. Ravi Parikh, and Dr. Avi Singh Gandhi were honored with AAPI’s prestigious Service Awards. Winners of the Research/Poster Presentation from across the nation who had presented the abstracts of their research on diverse medical topics, were honored with cash awards.

Reflecting back on AAPI’s progress over the last year, Dr. Sunil Kaza, the outgoing BOT Chair, said during the luncheon meeting, “Start of AAPI 2024-2025 term was like a storm, the likes of which, AAPI had never seen before !” and added, “Despite multiple and significant challenges, together with our EC, BOT and committee members, we have fulfilled our PROMISES.”

Dr. Hetral Gor shared with the audience, her journey as an ordinary member to how she has grown to be the chair of AAPI BOT. She described her plans for AAPI as the new Chair that she plans to initiative in collaboration with the new Executive Committee led by Dr. Amit Chakrabarty.

With the lighting of the traditional lamp and cutting the ribbon by Jacqueline Coleman, Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky, Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, president of the American Medical Association, Dr. D Nageshwar Reddy, a Padma Vibhushan awardee, Dr. Kathula, Dr. Sunil Kaza, outgoing Chair of AAPI BOT, Dr. Amit Chakrabarty, Dr. Hetal Gor, and Dr. Meher Medavram, President-Elect of AAPI. The ceremony began with the beautiful rendition of the national anthems of both the US and India by Dr. Aarti Pandya.

Speakers at the Convention included: Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, president of the American Medical Association; Dr. Lyuba Konopasek, MD, Senior Vice President, Intealth/ECFMG, Executive Director, FAIMER; Michael Suk, MD, BOT Chair, AMA; George Abraham, MD, Chair, Federation of State Medical Boards; and Dr. D Nageshwar Reddy, a Padma Vibhushan awardee. Dr. Mario Capecchi, a Nobel laureate, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology in 2007 for his contributions to the development of “Mouse knockout technology” delivered the keynote address at the AAPI Convention. Their addresses to the audience offered unprecedented insights into healthcare’s evolving landscape.

“I’ve been an AAPI member since I started medical school, and I’m an AMA member. But it’s like having a left hand and a right hand that don’t interact much. And that needs to be improved,” Dr. Bobby Mukamala, President of the American Medical Association, said in his keynote address. “I’m excited to be the first Indian descent president of the AMA to integrate that more. So that AAPI and the AMA both work together to improve physicians’ ability to take care of patients and the health of this country. Both are critical to make that happen, and if two critical aspects aren’t working together. We can work together, and we can watch them grow exponentially. When we work together, it will be exponential growth for both organizations.”

Jennifer Coleman, Lt. Governor of Kentucky, told AAPI members that, “We have so much appreciation for the work that you do, your compassion, the care that you provide, the long hours, the sacrifices that you make and that your families make. And you are the reason that the Governor and I refer to you as a title you have truly earned, which is healthcare heroes. So, thank you for what you do.”

Congressman Jonathan Jackson from Illinois, 1st congressional district sated, “Thank you for your outstanding leadership of this august body.”

Aftab Pureval, Mayor of Cincinnati, shared with the audience his life story as a child born to refugees from the Himalayas to the United States. “And it’s because of Trailblazers like you that next generations like me and my brother can pursue our dreams in whatever field that may be. Congratulations everybody! So excited for you to choose Cincinnati, and I hope you have a wonderful conference.”

The Convention was packed with 10 hours of Continuing Medical Education (CME) sessions delivered by world-renowned speakers, Women’s Forum, and specialized tracks on Medical Education and Medical Licensing, AAPI Has Got Talent, entertainment by world renowned artists, and upcoming talents from the local community.

“Whether you are a physician, a healthcare professional, or an industry partner, this convention has presented a valuable opportunity to showcase your business and connect with influential leaders in the medical field, said Dr. Meher Medavaram, President-Elect. “We are delighted to have you all in Cincinnati for this exceptional event.

The Convention delivered groundbreaking insights into modern healthcare, featuring top medical professionals from across the nation. Artificial Intelligence emerged as a critical theme, with Dr. Suresh Reddy and Dr. Nageshwara Rao explored AI’s transformative potential in healthcare delivery and patient management, while highlighting ethical considerations in medical technology.

Daily morning programs focused on sleep techniques and anxiety management, providing physicians innovative strategies for personal and professional well-being, emphasizing holistic professional development.

The Medical Licensing Forum, led by Dr. Amol Soin, brought together state medical board representatives to discuss critical practice pathways and professional standards. A comprehensive research symposium showcased cutting-edge medical research, with poster presentations and awards recognizing outstanding contributions to medical science.

According to Dr. Krishan Kumar, “The annual convention offered extensive academic presentations, recognition of achievements and achievers, and professional networking at the alumni and evening social events, in addition to offering an exciting venue to interact with leading physicians, healthcare industry leaders, academicians, and scientists of Indian origin.”

“The conference brought together acclaimed Physicians, healthcare professionals and leaders, in addition to including Academicians, Researchers and Medical students from across the world for a dynamic exchange of ideas, serving as a collaborative effort to shape the future of healthcare on a global scale,” Dr. Soumya Neravetla, Treasurer of AAPI said.

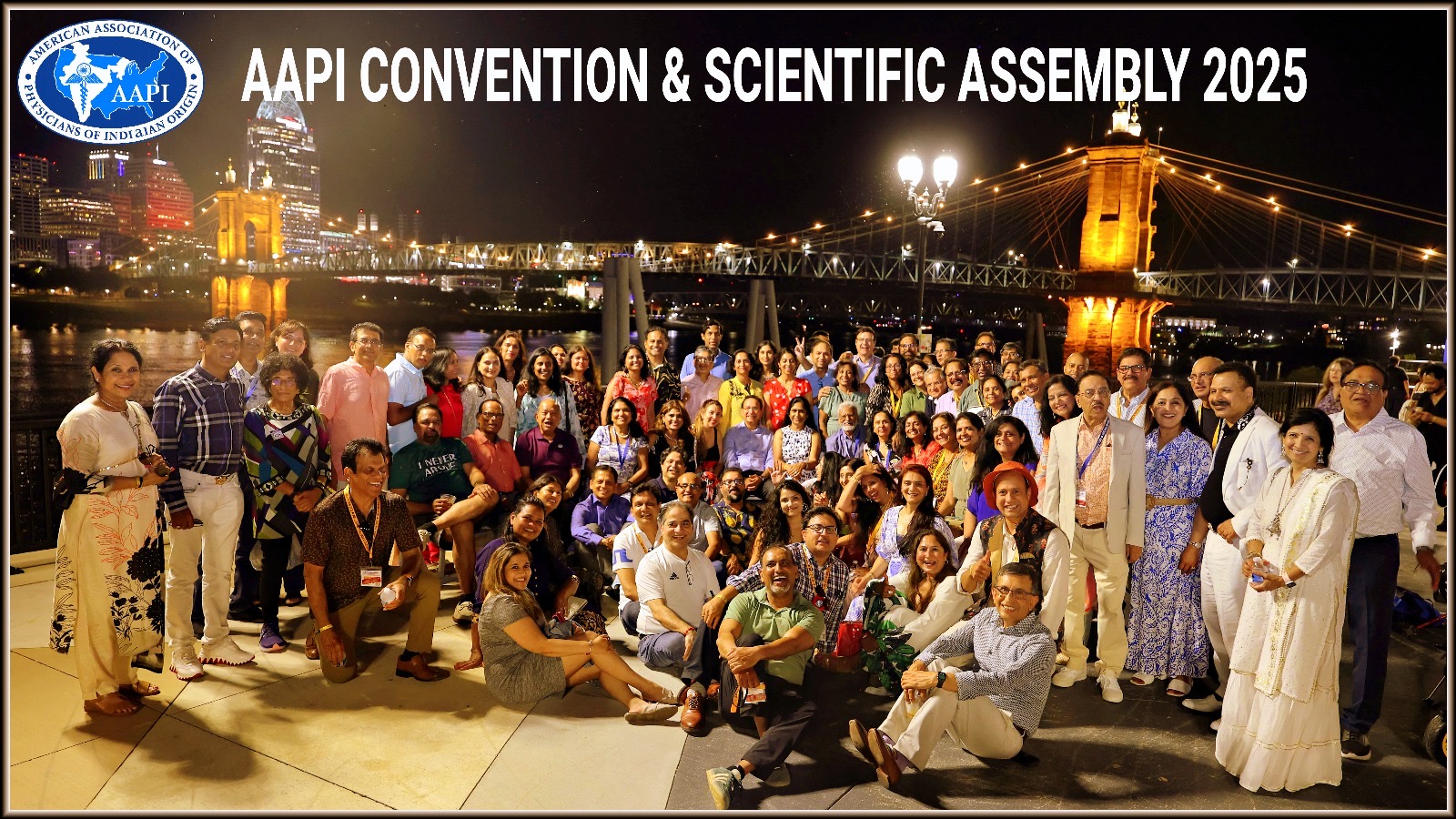

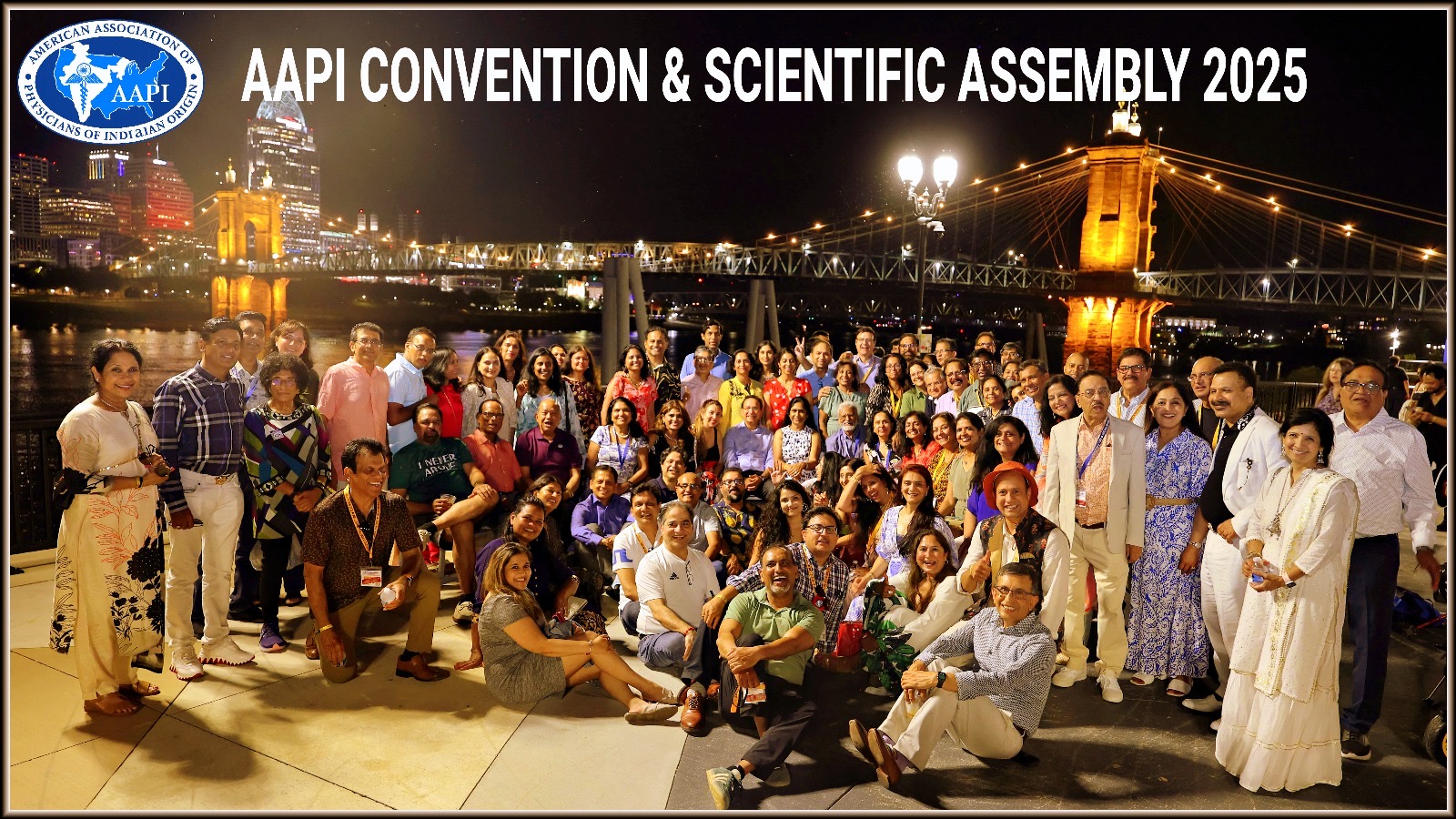

On July 24th, AAPI delegates had an exclusive Cruise on the majestic River Queen Boat at the famous Ohio River, with entertainment, live music, and dance. “It was such a memorable experience, having a glimpse at the skyline and watching the river on a sightseeing cruise along the Ohio River departing from the Kentucky side of Cincinnati, and experiencing live entertainment as you go,” said Dr. Hetal Gor. The Biriyani Nite with Bollywood music on the banks of the Ohio River that went into midnight was yet another experience for the AAPI delegates at the convention.

Special Highlights at the Convention included, Women’s Forum, Cultural Extravaganza, Networking opportunities, Cruise and Entertainment on the Ohio River and Gala dinners celebrating medical excellence. . In addition to the academic and professional offerings, attendees enjoyed three nights of world-class entertainment, making this a well-rounded and memorable gathering.

The convention successfully bridged medical expertise, technological innovation, and professional networking, setting new benchmarks for the future of healthcare.

Dr. Chakrabarty urged all AAPI members to join in this historic journey. “AAPI’s mission is clear, our programs will continue to strive, and our impact is infectious in benefiting society. Today I ask you to set aside your differences and join me in this noble journey to make our mission possible. A new era has begun. AAPI will continue to discover her own potential to be an active and vital player in shaping the landscape of the national healthcare delivery system with a focus on health maintenance than disease intervention,” Dr. Chakrabarty said.

Dr. Chakrabarty invited AAPI members to “come and participate at the 44th annual convention to be held in Tampa, FL from July 2nd to 5th, 2026. We look forward to having you all join us in Tampa, FL!” For more information on AAPI and the 44th convention, please visit: www.aapiconvention.org. For more details on AAPI, please visit: www.aapiusa.org

Ajay Ghosh

Media Coordinator, AAPI

Phone # 203.583.6750

Dr. Satheesh Kathula, the outgoing President of AAPI lauded the support and guidance he received from Dr. Kaza and other members of the BOT, including the incoming BOT Chair, Dr. Gor. Expressing his gratitude to AAPI’s executive committee members, including AAPI’s Convention committee chairs and members, volunteers and sponsors for their continued dedication and visionary leadership in their efforts to make this convention truly a historic one for all, Dr. Kathula, said. “The organizing committees have been working hard to make the AAPI Convention of 2025 rewarding and memorable for all.”

Dr. Satheesh Kathula, the outgoing President of AAPI lauded the support and guidance he received from Dr. Kaza and other members of the BOT, including the incoming BOT Chair, Dr. Gor. Expressing his gratitude to AAPI’s executive committee members, including AAPI’s Convention committee chairs and members, volunteers and sponsors for their continued dedication and visionary leadership in their efforts to make this convention truly a historic one for all, Dr. Kathula, said. “The organizing committees have been working hard to make the AAPI Convention of 2025 rewarding and memorable for all.”

The 23rd Biennial JAINA Convention, hosted by the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA) in collaboration with the Jain Society of Metropolitan Chicago (JSMC), took place at the Renaissance Schaumburg Convention Center and Hyatt Regency in Schaumburg, Illinois. From July 3 to July 6, 2025, the convention gathered delegates from 72 Jain Centers across the U.S. and Canada, alongside attendees from 10 other countries including India, the UK, Germany, Oman, Dubai, and Kenya. Celebrated under the theme “Unity in Diversity: A Path to Peace,” this event highlighted Jain principles such as Ahimsa (non-violence), Anekantvad (multiple viewpoints), and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness).

The 23rd Biennial JAINA Convention, hosted by the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA) in collaboration with the Jain Society of Metropolitan Chicago (JSMC), took place at the Renaissance Schaumburg Convention Center and Hyatt Regency in Schaumburg, Illinois. From July 3 to July 6, 2025, the convention gathered delegates from 72 Jain Centers across the U.S. and Canada, alongside attendees from 10 other countries including India, the UK, Germany, Oman, Dubai, and Kenya. Celebrated under the theme “Unity in Diversity: A Path to Peace,” this event highlighted Jain principles such as Ahimsa (non-violence), Anekantvad (multiple viewpoints), and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness). featuring Ashtapad—a unique creation showcasing 24 Tirthankaras—with sacred rituals and chants embracing the essence of Jainism. This was followed by the Exhibition Inauguration Ceremony displaying art, literature, and artifacts that emphasized the rich cultural heritage of Jainism.

featuring Ashtapad—a unique creation showcasing 24 Tirthankaras—with sacred rituals and chants embracing the essence of Jainism. This was followed by the Exhibition Inauguration Ceremony displaying art, literature, and artifacts that emphasized the rich cultural heritage of Jainism. Day two on July 4 began with calming yoga and meditation sessions, led by Samani Dr. Pratibha Pragyaji and Samani Punya Pragyaji, fostering inner peace among attendees. The day’s events included stirring speeches by JAINA President Bindesh Shah and JSMC President Pragnesh Shah, followed by a keynote by Pujya Dr. Gyanvatsal Swamiji on spiritual resilience. A variety of sessions included “મૈત્રીવાદ નો શંખવાદ” by Dr. Tej Sahebji and “The Most Urgent Act of True Ahimsa: What We Eat” by Dr. Faraz Harsini advocating for veganism.

Day two on July 4 began with calming yoga and meditation sessions, led by Samani Dr. Pratibha Pragyaji and Samani Punya Pragyaji, fostering inner peace among attendees. The day’s events included stirring speeches by JAINA President Bindesh Shah and JSMC President Pragnesh Shah, followed by a keynote by Pujya Dr. Gyanvatsal Swamiji on spiritual resilience. A variety of sessions included “મૈત્રીવાદ નો શંખવાદ” by Dr. Tej Sahebji and “The Most Urgent Act of True Ahimsa: What We Eat” by Dr. Faraz Harsini advocating for veganism. Empowerment Forum featuring Judge Neera Bahl among others. Keynote presentations and sessions explored diverse themes such as ecological crises and crisis care, enriching attendees with knowledge and inspiration. A blood drive that started on this day exemplified Jainism’s commitment to compassion, potentially impacting 276 lives.

Empowerment Forum featuring Judge Neera Bahl among others. Keynote presentations and sessions explored diverse themes such as ecological crises and crisis care, enriching attendees with knowledge and inspiration. A blood drive that started on this day exemplified Jainism’s commitment to compassion, potentially impacting 276 lives. Attendees gained perspectives from sessions such as Digital Karma by Pinkesh Shah, exploring AI’s ethical dimensions, alongside unity and diversity topics. The evening culminated with cultural performances and a keynote by Bollywood icon Sonu Sood emphasizing charitable actions.

Attendees gained perspectives from sessions such as Digital Karma by Pinkesh Shah, exploring AI’s ethical dimensions, alongside unity and diversity topics. The evening culminated with cultural performances and a keynote by Bollywood icon Sonu Sood emphasizing charitable actions. For the first time in the history of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI), during a formal ceremony Dr. Amit Chakrabarty and Dr. Hetal Gor were formally administered the oath of office as the President & Chairperson of the Board of Trustees of AAPI, respectively at a solemn ceremony at the AAPI office in Oak Brook, IL, on July 3rd, 2025.

For the first time in the history of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI), during a formal ceremony Dr. Amit Chakrabarty and Dr. Hetal Gor were formally administered the oath of office as the President & Chairperson of the Board of Trustees of AAPI, respectively at a solemn ceremony at the AAPI office in Oak Brook, IL, on July 3rd, 2025.

“We have the potential to make a significant impact on the healthcare landscape of this country,” Dr. Chakrabarty said. “My goal this year is to unify AAPI by transcending the regional divides that have hindered our progress in recent years. Indian American physicians represent tremendous talent and potential, and the key to realizing that lies in collective action and a united voice—something I am committed to fostering.”

“We have the potential to make a significant impact on the healthcare landscape of this country,” Dr. Chakrabarty said. “My goal this year is to unify AAPI by transcending the regional divides that have hindered our progress in recent years. Indian American physicians represent tremendous talent and potential, and the key to realizing that lies in collective action and a united voice—something I am committed to fostering.” Physician, serving as the Medical Director of Mount Sinai Hospital, FAQH Center, and a Staff Physician Advocate at Good Samaritan Hospital as well as a Clinical Preceptor at UIC College of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine CMU School of Medicine also was administered the oath of office as the President Elect of AAPI.

Physician, serving as the Medical Director of Mount Sinai Hospital, FAQH Center, and a Staff Physician Advocate at Good Samaritan Hospital as well as a Clinical Preceptor at UIC College of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine CMU School of Medicine also was administered the oath of office as the President Elect of AAPI. Serving 1 in every 7 patients in the US, AAPI members care for millions of patients every day, while several of them have risen to hold high-flying jobs, shaping the policies and programs, and inventions that shape the landscape of healthcare in the US and around the world.

Serving 1 in every 7 patients in the US, AAPI members care for millions of patients every day, while several of them have risen to hold high-flying jobs, shaping the policies and programs, and inventions that shape the landscape of healthcare in the US and around the world.