In a narrative that could rival Asia’s grandest movie plots, an unexpected love story has unfolded between Australia and the luminaries of Bollywood. Despite the considerable geographical distance, a genuine connection has burgeoned between the two realms, showcasing the depth of this cross-continental relationship.

Earlier this year, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese embarked on a journey to Delhi to engage with his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi. The discussions spanned a gamut of topics, encompassing trade, defense, and cricket. One particular announcement captured the headlines—an agreement on bilateral Audiovisual Co-production. This accord was designed to foster collaboration and cultural interchange through joint Indian-Australian film projects. Australian arts minister Tony Burke humorously referred to it as “bringing a slice of Bollywood to Brisbane.”

Contrary to its recent prominence, this bond traces back several decades, as depicted in the forthcoming documentary “Brand Bollywood – Downunder.” The film, set to debut this fall, delves into the expansion of ties between the Indian film industry and Australia since the late 1990s. Anupam Sharma, the documentary’s producer, writer, and director, was born in India but ventured to Australia as a child to visit relatives. In the 1990s, he enrolled in a Sydney film school, choosing acting as his sub-major.

In a video interview with CNN, Sharma reflected on those early days, saying, “There was a distinct lack of opportunities. I was doing the usual thing, playing a doctor or a spice shop owner in a TV commercial.” Fast forward to the present, and the landscape has transformed dramatically.

The shift is palpable in Melbourne, where the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, now in its 14th year and the largest of its kind outside India, has unfolded. Over ten days, more than 100 films in 20 languages are showcased, alongside panel discussions, an awards ceremony, and even a Bollywood dance competition.

Sharma narrates the evolution of this unique connection with a touch of serendipity. In 1997, a fortuitous twist of fate led him to seek out Feroz Khan, often referred to as “Bollywood’s Clint Eastwood,” who was visiting town. With a daring attitude, Sharma cold-called hotels, hoping to connect with the star. His gamble paid off when Khan’s assistant reached out for a meeting. This encounter led to a fruitful partnership, culminating in the production of “Prem Aggan” in 1998, a movie Khan directed, wrote, and Sharma produced.

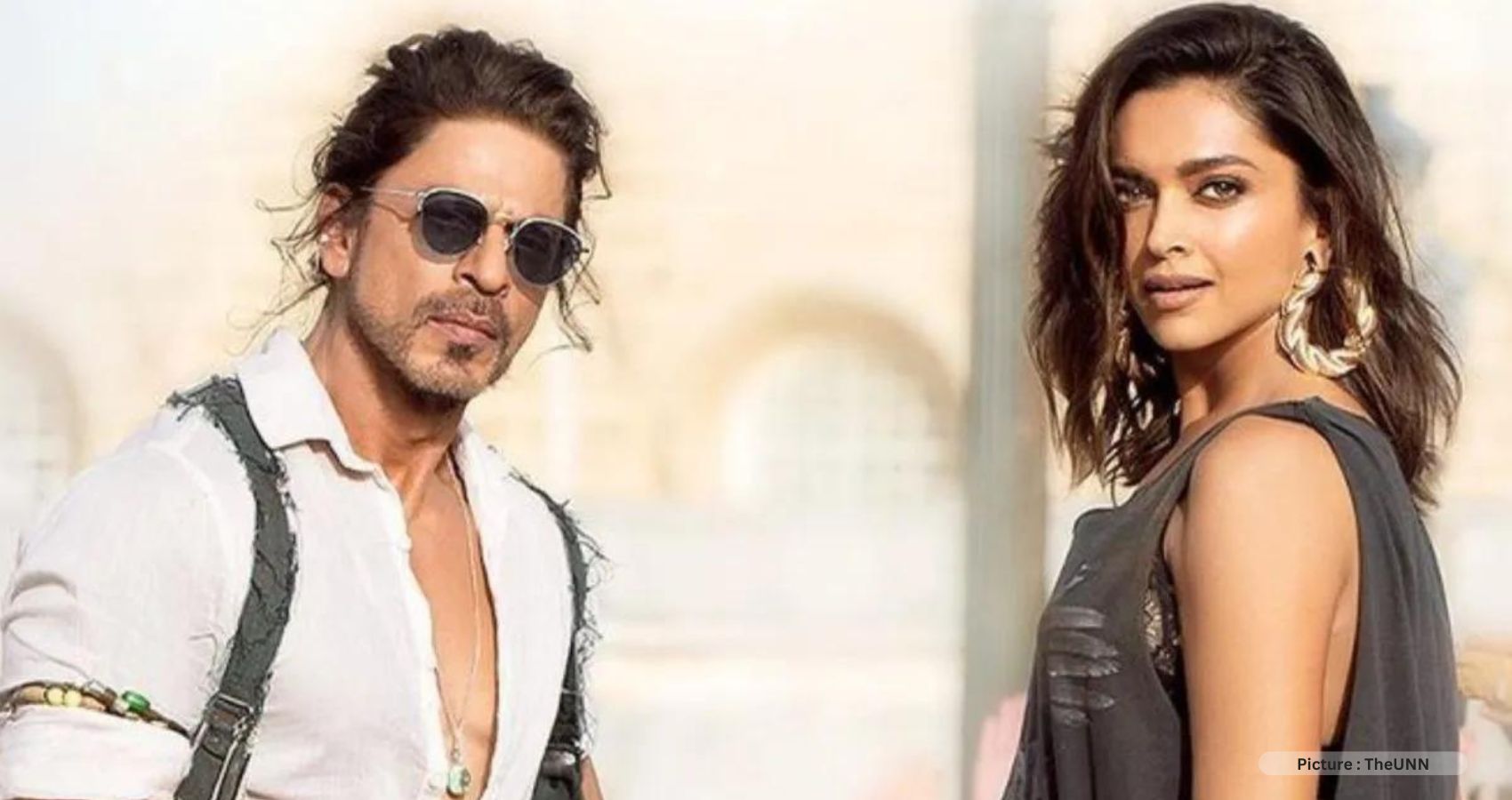

The collaboration gained momentum from there, with Khan pioneering the trend. Bollywood enthusiasts flocked to cinemas to witness stars performing exuberant song and dance routines against the backdrop of iconic Australian landmarks like the Sydney Opera House and the Twelve Apostles. A slew of Indian movies was filmed in Australia over the ensuing years.

In 2008, “Love Story 2050,” starring Harman Baweja and Priyanka Chopra, was shot in South Australia, becoming a significant moment in the cinematic landscape. Baweja shared that the film was a result of seamless production environments, efficient government support, and breathtaking locations. This cultural fusion was so impactful that the then-state premier Mike Rann even secured a cameo role.

As the success story spread, Australia encountered a deluge of requests, not only for visas for future productions but also from tourists eager to explore the movie locations. Sharma aptly described it as a “huge Bollywood bandwagon.”

The narrative shifted in 2009 when tensions emerged due to apparent racially motivated attacks on Indian students in Australia. This marked the end of the honeymoon period, but Sharma pointed out that the enthusiasm for collaboration persisted. He emphasized, “Australia realized that after ‘servicing’ Bollywood for over 13 years, it was time to shift gears and move to collaboration with Indian cinema.” This transition birthed a new phase, concentrating on shared narratives and narratives that highlighted the Indo-Australian experience.

In a tale where distance couldn’t deter the power of cinematic connection, Australia and Bollywood found themselves in an enduring love story, building bridges of creativity and culture across continents.

The unfolding romance between Australia and Bollywood has led to the creation of a new genre of films, characterized by a Western structure and an Indian essence. This bond has given rise to acclaimed movies like “Lion,” “Hotel Mumbai,” and Anupam Sharma’s very own creation, “UnIndian,” a romantic tale centered on an Australian woman with an Indian soul.

Describing this unique blend, Sharma elucidated, “It means films made with a Western beat – around 90 minutes long, not the three hours of Bollywood. The distribution, the financing, the structures, the editing are Western, but the soul, the emotions, the music, the drama is still Indian.” However, the term “Bollywood” occasionally stirs mixed feelings. Sharma acknowledged, “There are people who would swear at me for saying the word Bollywood.” He highlighted the diversity within the industry, likening it to an Indian goddess with multifaceted arms.

Australia has already formed 13 formal co-production partnerships with countries like Canada, China, and the UK. If India follows suit, it would unlock co-production opportunities, granting access to government funding, grants, loans, and tax offsets.

Once ratified by both the Australian and Indian parliaments, the Audiovisual Co-production Agreement could yield substantial benefits for both nations—both economically and culturally. Garth Davis, the Australian director of “Lion,” eagerly welcomed the prospect, emphasizing the enrichment that collaboration brings. He praised India’s history, humanity, and spirit, along with the exceptional skill level within the industry.

Salim and Sulaiman Merchant, Mumbai-based composers and musicians who worked on “UnIndian,” expressed their enthusiasm for more collaborations. Salim Merchant applauded Australia’s “vibe,” stating, “I think it’s wonderful there’s that synergy. Film is a beautiful medium. Making films that have both the diverse cultures and traditions creates a lot of love and respect between the two countries.”

The burgeoning audience for Bollywood productions in Australia has added to the allure of collaboration. The Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, initiated in 2010 by Mitu Bhowmick Lange, has drawn immense success. Lange set up the festival in response to her own desire to watch Indian films and has seen it grow beyond the Indian community. Australia’s Indian-born population is now the second-largest migrant community in the country, accounting for 9.5% of the overseas-born population and 2.8% of the total population.

As cultural connections deepen, both sides aspire to broaden their appeal. Sharma asserted, “Australia wants to boost its diversity credentials.” Simultaneously, Sharma noted a friend’s perspective that “Bollywood is not after a wider audience, but a Whiter audience.”

However, the shifting dynamics of global consumption seem promising. Lange observed, “The world is getting smaller and smaller, and streaming has changed everything.” She believes that the global appetite for foreign content has evolved, contributing positively to bridging cultural gaps.

The agreement’s potential is met with hope and optimism. Sharma stressed, “Indian films have always been a universal language for foreign governments to engage with India.” This alliance between Australia, a highly professional film industry, and India, a prolific cinematic powerhouse, is anticipated to be mutually beneficial. In Sharma’s words, “The marriage between the two has to be a win-win for both.”