Défense deals and tech ties underpin Modi’s visit to Washington.

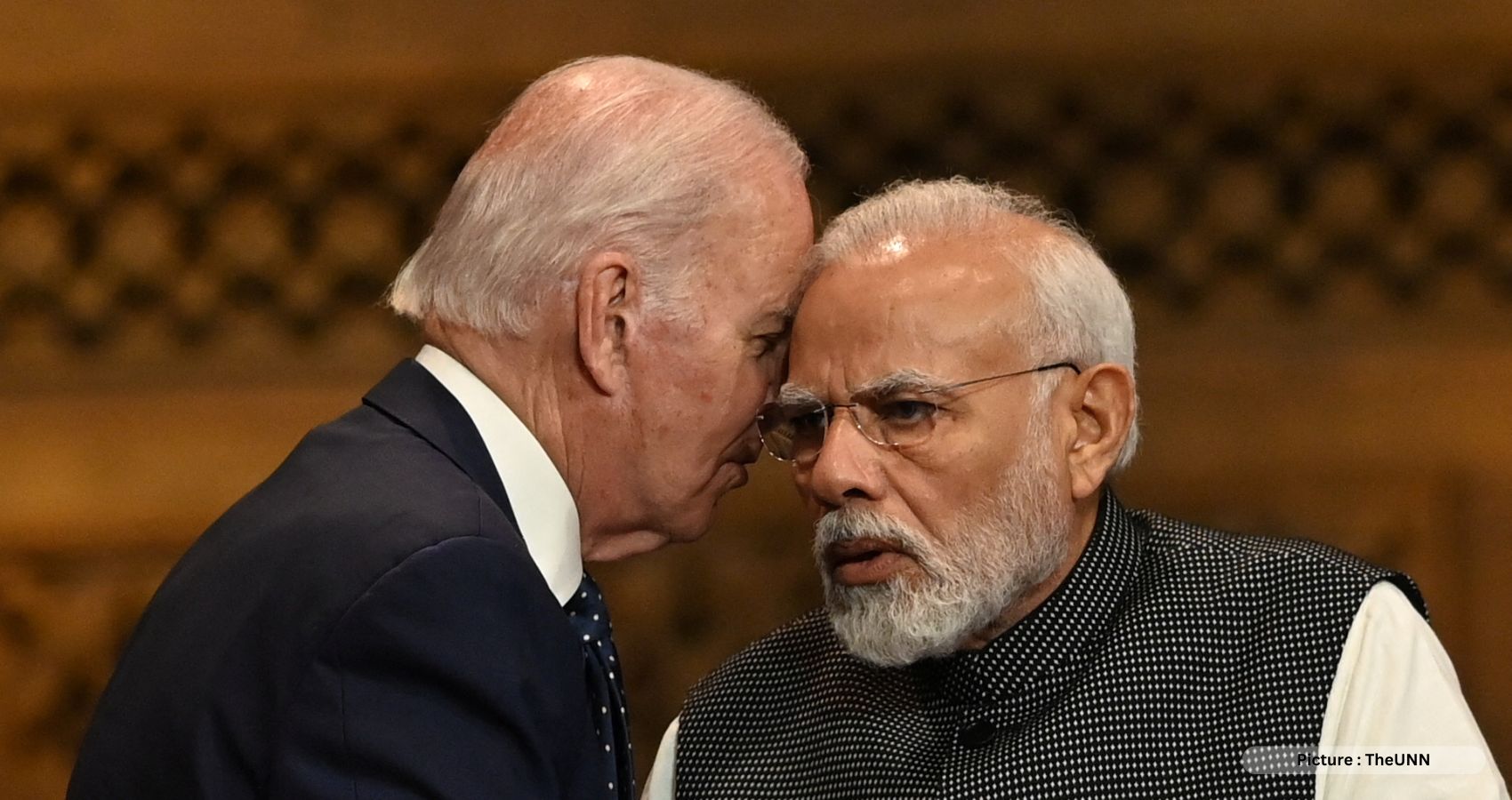

“My dream is that in 2020, the two closest nations in the world will be India and the United States,” then-Sen. Joe Biden said on a visit to New Delhi in 2006. They may not be quite there yet, but Biden is doing everything to ensure they end up much closer—especially economically and militarily—after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visits next week.

Washington is rolling out the red carpet for Modi, hosting him for a state dinner, the Biden administration’s third such visit after welcoming French President Emmanuel Macron and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol within the past year. Modi will also address a joint session of Congress, his second time doing so as Indian prime minister.

It’s not just pomp and symbolism, however. The United States wants to bring India deeper into its manufacturing and defense orbit, with the added benefit of helping wean New Delhi’s military off Russia and U.S. supply chains off China. Although both sides have been tight-lipped on planned announcements, a number of expected agreements on semiconductor chips and fighter jet engines have been in the works for months, bolstered by visits to New Delhi by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in the weeks leading up to Modi’s trip. This week, the two sides reportedly sealed a deal for India to buy more than two dozen American drones.

“While I will not spill the beans, I can tell you that the ceremonial and substantive parts of the visit will fully complement each other and will be unparalleled,” Taranjit Singh Sandhu, India’s ambassador to Washington, said at a recent event.

The India-U.S. relationship hasn’t always been smooth sailing, and potential frictions remain, but the two countries have increasingly zeroed in on an arena where they can achieve symbiosis. “If you ask me what I would bet on the most, what is that one force multiplier for this relationship, it is tech,” Sandhu said. “It is the master key to unlock the real potential in the relationship.”

Officials from both sides have spent months laying the groundwork—and acronyms. An initiative on critical and emerging technology (iCET), launched in late January by Sullivan and his Indian counterpart, Ajit Doval, commits to cooperation in areas such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, space exploration, semiconductors, and defense technology. There has been more movement on the last two in particular: U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal inked a bilateral semiconductor supply chain partnership in New Delhi in March, while Austin’s visit to New Delhi earlier this month yielded INDUS-X, or the India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem, described by the Pentagon as a “new initiative to advance cutting-edge technology cooperation” between the two militaries.

The most significant developments are likely to take place on the defense front, particularly if recent discussions on jointly producing jet engines, long-range artillery, and military vehicles come to fruition next week, product of a yearslong rapprochement on sharing defense technology with India. “This is not just manufacturing in India, this is genuine tech transfer,” said Rudra Chaudhuri, director of New Delhi-based think tank Carnegie India. “That’s a big deal.”

In some ways, it is an opportunity for a marriage of convenience. About half of India’s military equipment is Russian-made, and although New Delhi has spent years trying to diversify that supply, Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine has increased the urgency of finding new bedfellows. Washington sees an opening.

“The one relationship which the U.S. has traditionally been wary of in closer defense ties with India has been the India-Russia partnership,” said Aparna Pande, director of the India Initiative at the Hudson Institute. “This is one chance where if India can be weaned away because of a lack of supply parts, problematic equipment, or Russia getting closer to China, [you can] maybe convince India to purchase more from the United States and U.S. partners and allies.”

China is another major source of mutual concern pushing Washington and New Delhi closer together. India’s relationship with China deteriorated earlier and far more dramatically, with military clashes on their shared border leading to an Indian purge of Chinese technology (including, notably, a TikTok ban) nearly three years ago. Chinese naval expansion into the Indian Ocean has also spooked India and reinforced the importance of the so-called Quad group of countries. The United States and its allies, meanwhile, are urgently trying to reorient and “friendshore” global tech supply chains to reduce dependence on China, which has spent years establishing itself as the world’s factory floor.

India presents a ready replacement in many ways, much of it stemming from its new status as the world’s most populous country. That means a large (and youthful) labor force, millions of whom are skilled engineers, and relatively low manufacturing costs that the Modi government is further bolstering with tax incentives under its signature “Make in India” program. Like China, India’s sheer size also presents a huge potential domestic market for U.S. companies, an advantage over other alternatives such as Vietnam and Mexico. If for decades dollars and cents determined the landscape of global technology production, geopolitics have become supreme.

“There’s a sense of Balkanization taking place” in the global tech supply chain, said Mukesh Aghi, CEO of the U.S.-India Strategic Partnership Forum, a Washington-based business advocacy group. “Geopolitical stress points are driving the tech agenda.”

There are still hurdles that need to be overcome, including India’s history of protectionism and red tape that has burned U.S. companies in the past and made it difficult to create the kind of manufacturing infrastructure required to rival what China has built. One large semiconductor push, a $19 billion joint venture between Indian conglomerate Vedanta and Taiwanese manufacturer Foxconn, has reportedly already been stymied by a denial of government incentives.

And while companies will ultimately have to vote with their checkbooks, Biden and Modi are sending nothing but boosterish signals.

“Remember the old saying that trade follows the flag—I think the two governments are waving the flag very mightily to show which direction industry and business ought to be going,” said Atul Keshap, a former diplomat who heads the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s U.S.-India Business Council. “The two governments tried for a long time to figure out what government-to-government interaction would look like, and now I think they’re realizing the value of letting the private sector collaborate,” he added.

But one casualty of the Modi visit and his newfound status will likely be U.S. willingness to call out concerns about the health of India’s democracy, at least publicly. The Biden administration has been increasingly reluctant to call out Modi’s crackdowns on free speech and violence against minorities, and experts say the strategic imperatives are too great to afford antagonizing a vital partnership.

“There is a desire to emphasize the strategic and the national security imperative over the domestic imperative,” Pande said. “In the current context, India is important, and so what the U.S. is preferring to do is convey a lot of what it wants to say in private and not in public.”

(Rishi Iyengar is a reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @Iyengarish)