A class war is being waged in the name of fighting inflation. All too many central bankers are raising interest rates at the expense of working people’s families, supposedly to check price increases.

Forced to cope with rising credit costs, people are spending less, thus slowing the economy. But it does not have to be so. There are much less onerous alternative approaches to tackle inflation and other contemporary economic ills.

Short-term pain for long-term gain?

Central bankers are agreed inflation is now their biggest challenge, but also admit having no control over factors underlying the current inflationary surge. Many are increasingly alarmed by a possible “double-whammy” of inflation and recession.

Nonetheless, they defend raising interest rates as necessary “preemptive strikes”. These supposedly prevent “second-round effects” of workers demanding more wages to cope with rising living costs, triggering “wage-price spirals”.

In central bank jargon, such “forward-looking” measures convey clear messages “anchoring inflationary expectations”, thus enhancing central bank “credibility” in fighting inflation.

They insist the resulting job and output losses are only short-term – temporary sacrifices for long-term prosperity. Remember: central bankers are never punished for causing recessions, no matter how deep, protracted or painful.

But raising interest rates only makes recessions worse, especially when not caused by surging demand. The latest inflationary surge is clearly due to supply disruptions because of the pandemic, war and sanctions.

Raising interest rates only reduces spending and economic activity without mitigating ‘imported’ inflation, e.g., rising food and fuel prices. Recessions will further disrupt supplies, aggravating inflation and worsening stagflation.

Wage-price spirals?

Some central bankers claim recent instances of wage increases signal “de-anchored” inflationary expectations, and threaten ‘wage-price spirals’. But this paranoia ignores changed industrial relations and pandemic effects on workers.

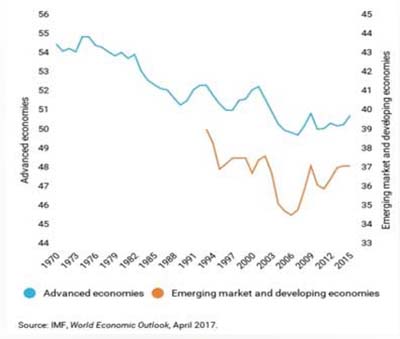

With real wages stagnant for decades, the ‘wage-price spiral’ threat is grossly exaggerated. Over recent decades, most workers have lost bargaining power with deregulation, outsourcing, globalization and labour-saving technologies. Hence, labour shares of national income have declined in most countries since the 1980s.

Labour market recovery, even tightening in some sectors, obscures adverse overall pandemic impacts on workers. Meanwhile, millions of workers have gone into informal self-employment – now celebrated as ‘gig work’ – increasing their vulnerability.

Pandemic infections, deaths, mental health, education and other impacts, including migrant worker restrictions, have all hurt many. Contagion has especially hurt vulnerable workers, including youth, migrants and women.

Workers’ share of national income, 1970-2015

Ideological central bankers

Economic policies by supposedly independent and knowledgeable technocrats are presumed to be better. But such naïve faith ignores ostensibly academic, ideological beliefs.

Typically biased, albeit in unstated ways, policy choices inevitably support some interests over – even against – others. Thus, for example, an anti-inflation policy emphasis favours financial asset owners.

Politicians like the notion of central bank independence. It enables them to conveniently blame central banks for inflation and other ills – even “sleeping at the wheel” – and for unpopular policy responses.

Of course, central bankers deny their own role and responsibility, instead blaming other economic policies, especially fiscal measures. But politicians blaming central bankers after empowering them is simply shirking responsibility.

In the rich West, governments long bent on fiscal austerity left the heavy lifting for recovery after the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC) to central bankers. Their ‘unconventional monetary policies’ involved keeping policy interest rates very low, enabling corporate shenanigans and zombie business longevity.

This enabled unprecedented increases in most debt, including private credit for speculation and sustaining ‘zombie’ businesses. Hence, recent monetary tightening – including raising interest rates – will trigger more insolvencies and recessions.

German social market economy

Inflation and policy responses inevitably involve social conflicts over economic distribution. In Germany’s ‘free collective bargaining’, trade unions and business associations engage in collective bargaining without state interference, fostering cooperative relations between workers and employers.

The German Collective Bargaining Act does not oblige ‘social partners’ to enter into negotiations. The timing and frequency of such negotiations are also left to them. Such flexible arrangements are said to have helped SMEs.

Although Germany’s ‘social market economy’ has no national tripartite social dialogue institution, labour unions, business associations and government did not hesitate to democratically debate crisis measures and policy responses to stabilize the economy and safeguard employment, e.g., during the GFC.

Dialogue down under

A similar ‘social dialogue’ approach was developed by Australian Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke from 1983. This contrasted with the more confrontational approaches pursued in Margaret Thatcher’s UK and Ronald Reagan’s USA – where punishing interest rates inflicted long recessions.

Although Hawke had been a successful trade union leader, he began by convening a national summit of workers, businesses and other stakeholders. The resulting Prices and Incomes Accord between the government and unions moderated wage demands in return for ‘social wage’ improvements.

This consisted of better public health provisioning, pension and unemployment benefit improvements, tax cuts and ‘superannuation’ – involving required employees’ income shares and matching employer contributions to a workers’ retirement fund.

Although business groups were not formally party to the Accord, Hawke brought big businesses into other new initiatives such as the Economic Planning Advisory Council. This consensual approach helped reduce both unemployment and inflation.

Such consultations have also enabled difficult reforms – including floating exchange rates and reducing import tariffs. They also contributed to the developed world’s longest uninterrupted economic growth streak – without a recession for nearly three decades, ending in 2020 with the pandemic.

Social partnerships

A variety of such approaches exist. For example, Norway’s kombiniert oppgjior, from 1976, involved not only industrial wages, but also taxes, salaries, pensions, food prices, child support payments, farm support prices, and more.

‘Social partnerships’ have also been important in Austria and Sweden. A series of political understandings – or ‘bargains’ – between successive governments and major interest groups enabled national wage agreements from 1952 until the mid-1970s.

‘Social partnerships’ have also been important in Austria and Sweden. A series of political understandings – or ‘bargains’ – between successive governments and major interest groups enabled national wage agreements from 1952 until the mid-1970s.

Consensual approaches undoubtedly underpinned post-Second World War reconstruction and progress, of the so-called Keynesian ‘Golden Age’. But it is also claimed they have created rigidities inimical to further progress, especially with rapid technological change.

Economic liberalization in response has involved deregulation to achieve more market flexibilities. But this approach has also produced more economic insecurity, inequalities and crises, besides stagnating productivity.

Such changes have also undermined democratic states, and enabled more authoritarian, even ethno-populist regimes. Meanwhile, rising inequalities and more frequent recessions have strained social trust, jeopardizing security and progress.

Policymakers should consult all major stakeholders to develop appropriate policies involving fair burden sharing. The real need then is to design alternative policy tools through social dialogue and complementary arrangements to address economic challenges in more equitably cooperative ways.

Studying China’s loan arrangements for 13,427 projects in 165 countries over 18 years,

Studying China’s loan arrangements for 13,427 projects in 165 countries over 18 years,