Previewing Donald Trump’s second inaugural address, several of his political advisors suggested that its tone would be gentler and its substance more unifying than was his “American Carnage” inaugural address eight years ago. They must have been misinformed as his spoken words continued to emphasize American crisis and decline and were hardly unifying or uplifting.

While there were occasional rhetorical bows toward unity, the thrust of the speech was an all-out assault on illegal immigration and on aspects of American culture loathed by social conservatives (with scant attention to any plans to bring down the cost of living, one of the issues that elected him). He wants to be a peacemaker overseas but a warrior at home. And in a speech traditionally devoted to selfless themes, President Trump spoke about the extent of his electoral victory and professed his belief that he had been saved by God to save the nation.

The speech celebrated the broadening of the Republican coalition that Trump has achieved. He praised Martin Luther King and promised that “we will strive to make his dream a reality.” To the Black and Hispanic communities, he said, “I want to thank you, we set records [measured in votes] and I will not forget it.” Absent, however, was a nod to President Biden, Vice President Harris, or any of his predecessors—or an olive branch to the 48.4% of Americans who voted for Harris.

Surprisingly, President Trump had little to say about his economic plans or efforts to tackle inflation, preferring instead to spend much of his time on the “invasion” of illegal immigrants into this country. Indeed, this was the portion of the address that was most detailed and concrete. To counter this “invasion,” Trump promised to declare a national emergency at the southern border, reinstate the remain in Mexico policy, end the practice of catch and release, send troops to the southern border, and designate cartels as foreign terrorist organizations.

In addition to the war at the southern border Trump, promised to wage a culture war, which he termed a “revolution of common sense.” Under his administration, the United States government would only recognize two genders, male and female, eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs in the government (especially in the military), and “end the practice of trying to engineer race and gender into every aspect of public life.”

Trump promised a golden age with no new overseas wars. He did not mention Russia or the war in Ukraine, but he did note his plan to expand our nation, including “increas[ing] our territory” and “[planting] the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars.” (Elon Musk smiled broadly at this phrase.) He declared that “We didn’t give the Panama Canal to China, we gave it to Panama, and we’re taking it back.” He did not say how he would do this without starting a new war.

The newly inaugurated president used the occasion to announce two name changes. The Gulf of Mexico will henceforth be called “the Gulf of America,” and Mount Denali will revert to its name before the Obama administration—Mount McKinley. Indeed, William McKinley (who was a big fan of tariffs) seems to have replaced Andrew Jackson as Trump’s favorite president. What this portends for the fate of economic populism in the new administration is anyone’s guess. But it cannot be an accident that Trump chose to resuscitate the phrase “manifest destiny.” We will find out whether our destiny includes control of Greenland and Canada, as he has suggested.

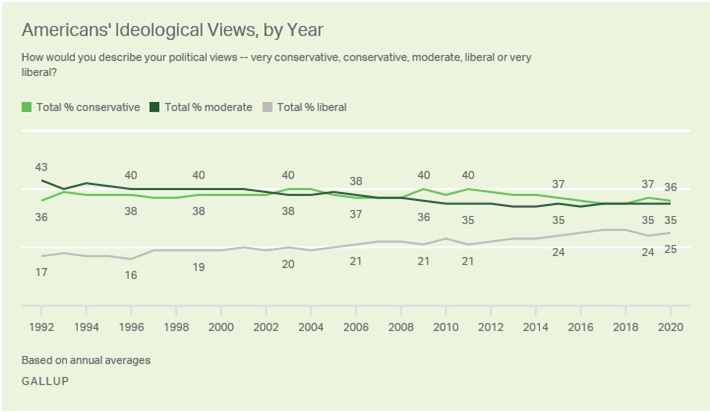

Along with his unscripted speech later in the afternoon that talked about the stolen 2020 election and his grievances against political opponents, Trump’s second inaugural address is consistent with his campaign, in which he worked tirelessly to intensify his support rather than broaden it. If he wishes to maintain majority support, however, he must recognize that the voters who put him over the top were not fervent MAGA supporters but rather swing voters who decided that he offered a better chance than his opponent of solving specific problems, high prices for the basics of daily life first among them. If he governs as a hardliner on immigration and cultural issues, he may solidify his loyal base, but if he fails to take down high prices or restore economic hopes of upward mobility, he risks losing swing voters while reenergizing his disheartened opponents. In an era of narrow and shifting majorities, this is a risk that he ignores at his peril.

Despite the fact that Rudy Giuliani led New York City for two mayoral terms, followed by Mike Bloomberg for three terms, many observers persist in viewing New York City as the most liberal big city in America, with the possible exception of San Francisco. It came as a surprise to them that in the recent mayoral race, the winner and the strong second place finisher were not the most left-wing candidates. The winner, Eric Adams, ran as a law-and-order centrist and establishment politician; the second-place finisher, Kathryn Garcia, ran on her experience in city government. Left-wing voters coalesced around Maya Wiley, who won the endorsement of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Ortiz. Wiley came in third, and Andrew Yang, another moderate candidate who allied himself with Garcia in the campaign’s closing weeks, finished fourth.

Despite the fact that Rudy Giuliani led New York City for two mayoral terms, followed by Mike Bloomberg for three terms, many observers persist in viewing New York City as the most liberal big city in America, with the possible exception of San Francisco. It came as a surprise to them that in the recent mayoral race, the winner and the strong second place finisher were not the most left-wing candidates. The winner, Eric Adams, ran as a law-and-order centrist and establishment politician; the second-place finisher, Kathryn Garcia, ran on her experience in city government. Left-wing voters coalesced around Maya Wiley, who won the endorsement of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Ortiz. Wiley came in third, and Andrew Yang, another moderate candidate who allied himself with Garcia in the campaign’s closing weeks, finished fourth.