While both political parties have long coveted the women’s vote, for the most part in recent decades, it has helped Democrats. And in Tuesday’s midterm elections, this group will again be closely watched, as it will be especially affected by the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, which effectively allows states to enact restrictive abortion provisions.

The fear among many pro-choice voters, particularly women, is that a Republican-dominated Congress could use this ruling as a premise to enact a nationwide abortion ban. A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that half or more of respondents are more motivated to vote in this year’s midterms because of abortion concerns, especially among women. And according to an Economist/YouGov poll conducted October 29 through November 1, 60% of women said that views on abortion mattered a lot in their voting, compared to 40% of men.

While polls indicate that women are more likely than men to favor Democrats in a national generic ballot for House of Representatives candidates, these do not reflect actual votes. They also do not show how those polling results apply to eligible voters. This analysis looks at both, using the most recent eligible voter populations compiled by the Census Bureau’s September 2022 Current Population Survey and applying to them voter turnout rates from the 2018 midterm and assumptions about 2022 voting. Through simulations, it shows how increased women’s turnout and voter preferences could impact national election results and specific battleground states. These simulations make clear that more pronounced turnout and Democratic voting preferences among women would benefit Democrats considerably.

WOMEN LEAN TOWARD DEMOCRATIC CANDIDATES, AND TURN OUT TO VOTE AT HIGHER RATES

In order to assess the role that women have in determining the midterm election results, it is important to view gender differences in both voting preferences and turnout. When examining national numbers, women overall have voted for Democrats over Republicans in every presidential and midterm election since 1982.[i]

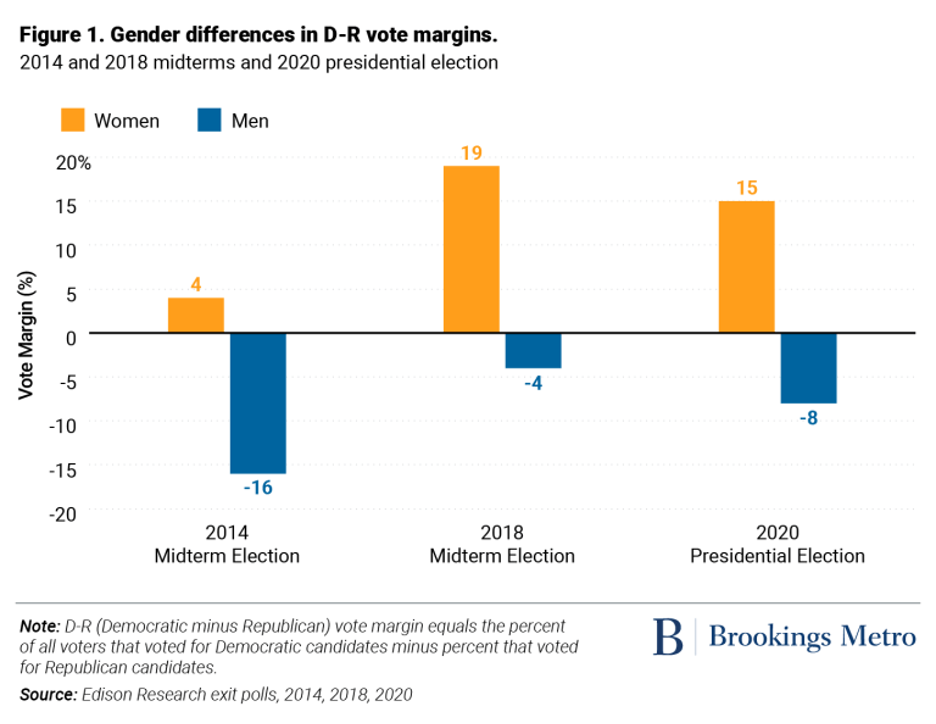

This is evident in Figure 1, which shows the D-R (Democratic minus Republican) vote margins by gender for national cumulative House of Representatives votes in 2014 and 2018 and for the 2020 presidential election. In each case, the D-R margins are positive for women and negative for men. The 2018 midterm election was a particularly strong year for Democrats, with women’s D-R margin far exceeding that for the 2014 midterms, while men’s negative D-R margin was noticeably smaller.

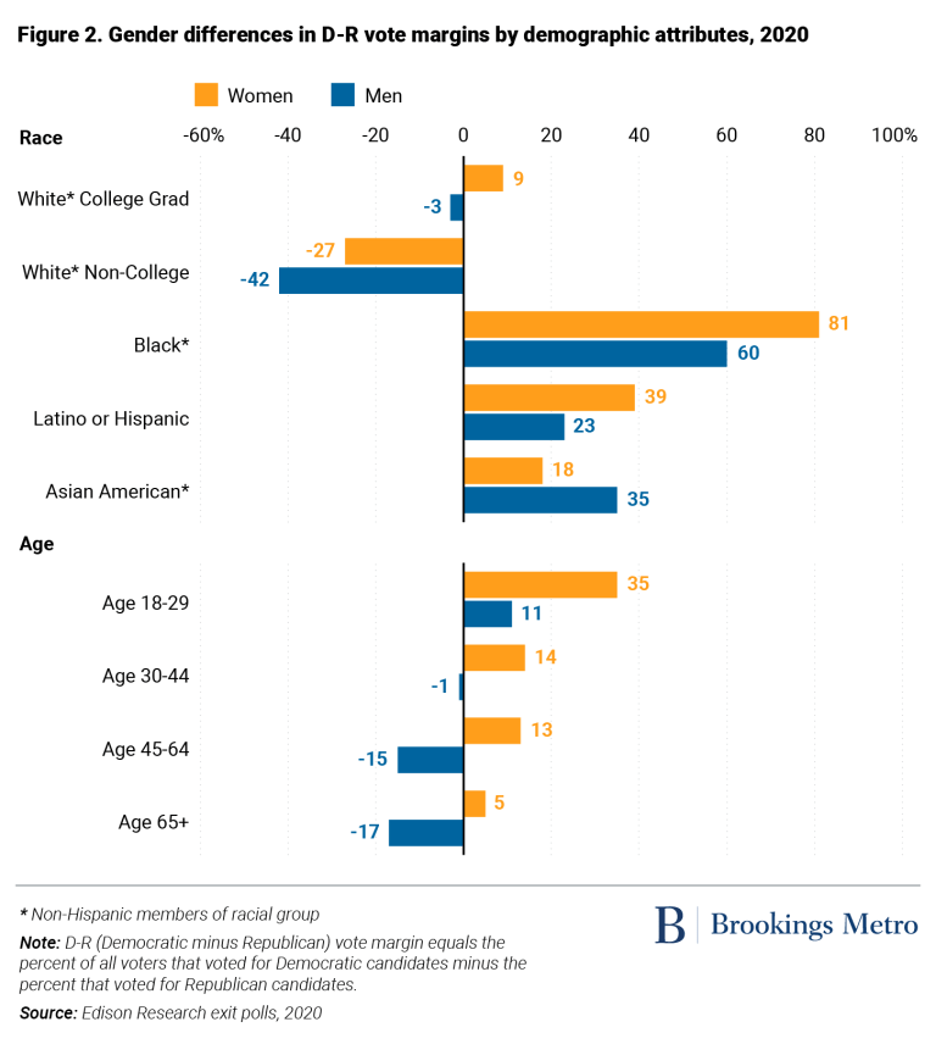

Gender differences also pervade demographic groups. This is evident for the 2020 presidential election as shown in Figure 2, although it was also pervasive in earlier elections. D-R margins are higher for women than for men in groups where women vote strongly Democratic: Black voters, Latino or Hispanic voters, and voters aged 18 to 29. Even for white, non-college graduate women voters—who favored Republicans—the negative D-R margins are not as large as those of men. Only among Asian American voters were men’s D-R margins higher than women’s.

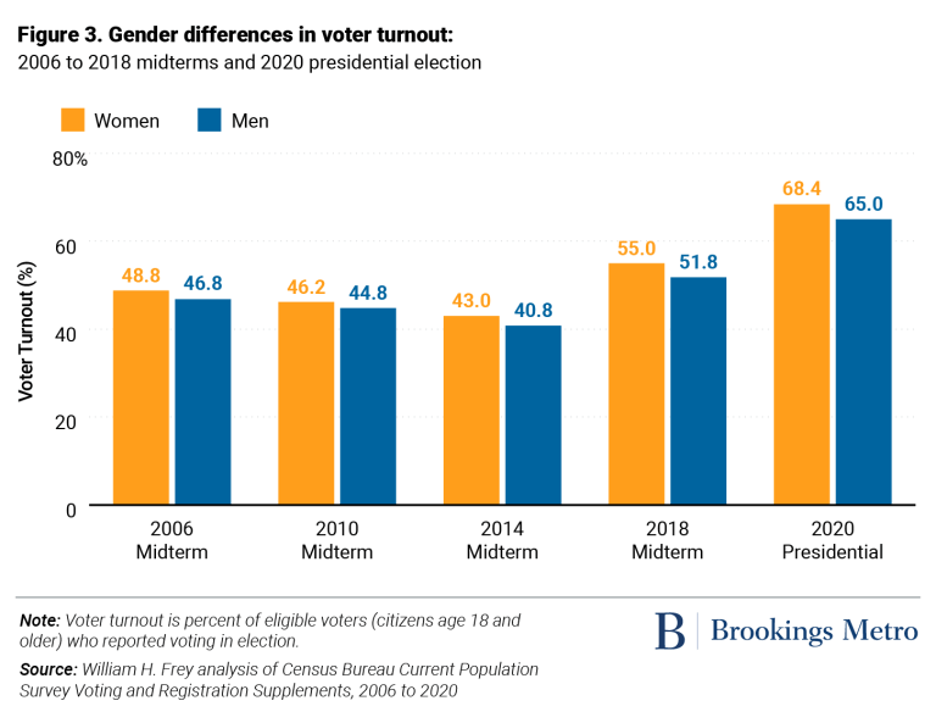

Perhaps even more important in examining women’s power in the coming election is their continued higher turnout rate. There is a long history of higher turnout levels for women than men, dating back to 1980. While the pattern is more pronounced for presidential elections, it is also the case for midterm elections. Figure 3 depicts gender differences in turnout for midterm elections from 2006 to 2018 and the 2020 presidential election. The 2018 midterm showed the highest turnout in decades, as was the case for the 2020 presidential election. In both of these elections, the rise in turnout among women was greater than that of men. Because of this and the fact that women live longer than men, the 2018 election had 8.4 million more female voters than male voters; in the 2020 election, there were 9.7 million more female voters.

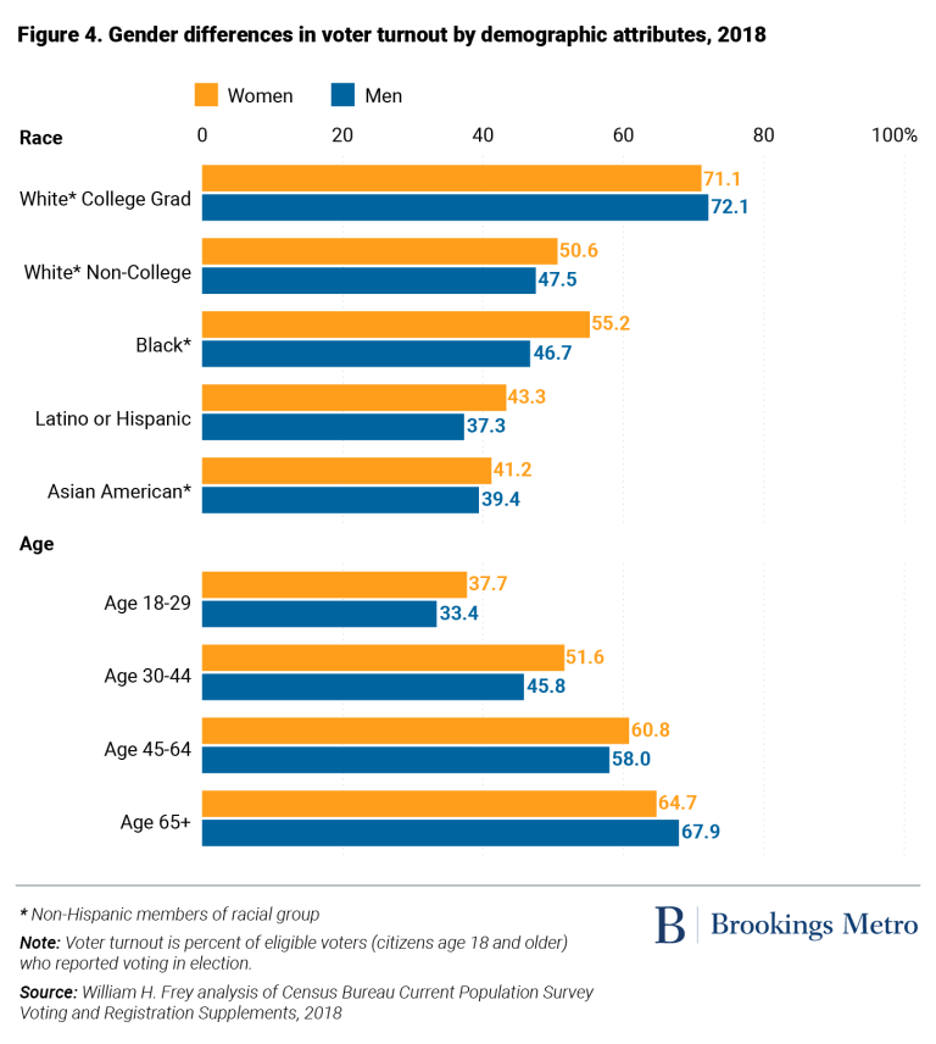

In addition to the overall numeric advantage, women have higher turnout rates across most demographic groups. This is noteworthy among Black women—a strong Democratic voting bloc that in 2018 turned out at 55.2%, compared with 46.7% for Black men. Both white women and white men with college degrees turned out at similar high rates: 71.1% and 72.1%, respectively. Among age groups, women show turnout advantages for all except the 65 and older group, even though women make up 55% of all eligible voters among that group.

Overall, women’s numeric vote advantage in most groups coupled with their broad Democratic leanings make any issues that motivate them to vote Democratic—such as abortion—important to monitor in an election.

THE FEMALE ELECTORATE IS CHANGING

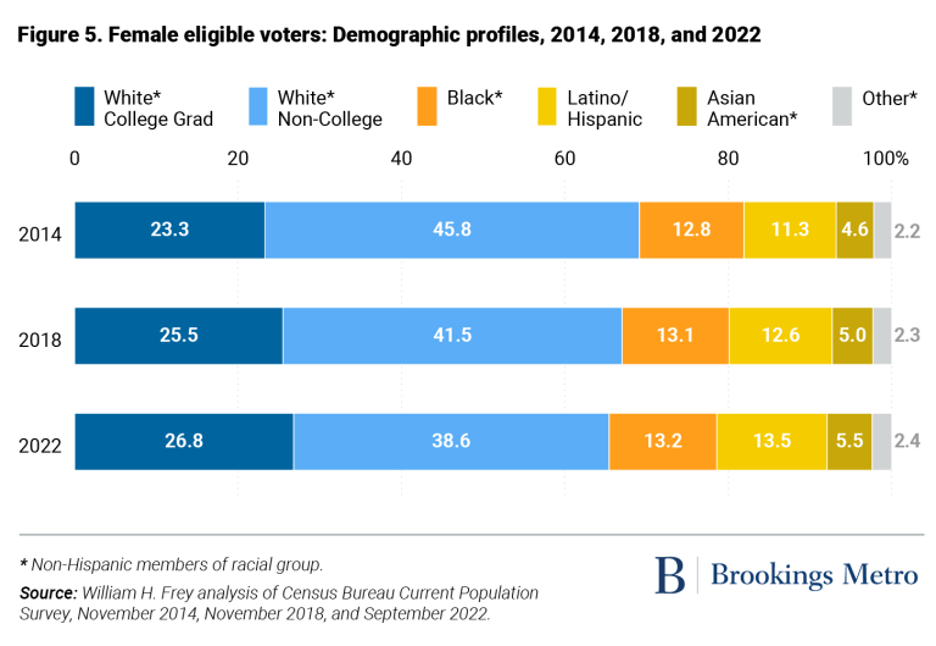

While the size of the female electorate is increasing, its demographic makeup is changing. Figure 5 shows the shifts in women’s eligible voter profile between 2014 and 2022 by race and education. Notably, there are gains in women’s groups that tend to vote Democratic (white college graduates and people of color), and a decline in the group that tends to vote Republican (white non-college graduates). For the first time in a midterm election, the latter group makes up less than two-fifths of the women’s electorate.

Compared to women, male eligible voters have slightly higher shares of white non-college graduates and smaller shares of white college graduates (downloadable Table A). With respect to age, both female and male eligible voters show older age profiles over time. In 2022, women age 65 and over make up one-quarter of the eligible voter population, while men in that age group make up 22.3%.

SIMULATING THE 2022 GENERIC CONGRESSIONAL BALLOT

As mentioned earlier, recent polls provide some indication of what the midterm election results will be, but they do not take into account the relative size of the voter population, relative turnout rates, and possible last-minute changes in voter preference. This section presents three simulations based on female and male eligible voter populations, turnout rate assumptions, and gender differences in voter preferences based on the polling numbers in the recent Economist/YouGov poll.

In that poll, 51% of women choose a Democratic candidate for a generic 2022 congressional ballot, 46% choose a Republican candidate, and 3% choose other, are not sure, or will/did not vote. Among men, 45% choose a Democratic candidate, 51% choose a Republican candidate, and 4% choose the other categories.

The simulations below show what would happen if, because of concern about abortion, women’s turnout increased by 10 points and women’s Democratic preference increased by 3 points (converting the residual category to Democratic support).

Simulation 1: Assumes 2022 eligible voters by gender, 2018 turnout rates by gender, and 2022 Democratic-Republican congressional preferences by gender

Democratic vote share: 48.2%

Republican vote share: 48.4%

D-R vote margin: -0.2

Simulation 2: Same as Simulation 1, with women’s turnout increased by 10 points

Democratic vote share: 48.4%

Republican vote share: 48.1%

D-R vote margin +0.3

Simulation 3: Same as Simulation 2, with women’s Democratic preference increased by 3 points

Democratic vote share: 50.1%

Republican vote share: 48.1%

D-R vote margin +2.0

The results show that when applied to current female and male eligible voter populations, recent polling would result in a close election outcome with a small Republican advantage. But if the abortion issue motivates greater female turnout and Democratic voting preference, the advantage turns to Democrats.

SIMULATING 2022 ELECTION RESULTS IN BATTLEGROUND STATES

While the national simulations are instructive, great attention will be paid to battleground states with key Senate and gubernatorial elections. This section continues our analysis with simulations for nine of these battleground states: in the North, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin; in the South, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas; and in the West, Nevada and Arizona. Each of these has a Senate election except Texas, which has a gubernatorial election.

In place of new polling data, which is not uniformly available for these states, our simulations rely on Democratic and Republican votes by gender from the 2020 presidential election as a baseline (with the exception of Georgia, where votes for the 2020 Senate runoff election were used). These are depicted as women’s and men’s D-R vote margins for each state in Figure 6.

In each state, women overall voted Democratic and men overall voted Republican. Yet the strength of each gender’s support differs, with highest female Democratic support occurring in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Georgia and strongest male Republican support in Texas.

In terms of gender differences in turnout rates, each state also showed higher female voter turnout in the 2018 midterm election, with especially strong gender disparities in Ohio and Georgia (downloadable Table B). In the former, women turned out at 55.9% while men turned out at 48.9%; in the latter, the respective rates were 58.3% and 53.1%

It is also worth noting the differences in the race and education profiles of each state’s 2022 eligible voter populations (downloadable Table B). The states with the highest number of Latino or Hispanic eligible voters among both women and men are Texas, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida. Those with the highest number of Black eligible voters are Georgia and North Carolina. Wisconsin, Ohio, and Pennsylvania have the largest number of white eligible voters. It is notable that in Ohio and Wisconsin, over half of all eligible male and female voters are white non-college graduates. In Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, more than 30% of female eligible voters are white college graduates, and in all states, a higher share of men are white non-college graduates than women.

The three state simulations shown in Table 1 follow a similar methodology as used in the national simulations. The base simulation employs 2022 eligible voter populations by gender, to which are applied 2018 turnout rates and Democratic and Republican voter preference—in this case based on the 2020 election. The second simulation assumes that women’s turnout rates are increased by 10 points. The third simulation further assumes that each state’s D-R vote margin for women increases by 5 points.

The base simulation shows an overall Democratic win in five of the nine states. The D-R margins are largest in Nevada, Wisconsin, and Georgia, followed by Arizona and Pennsylvania. Four states—North Carolina, Ohio, Florida, and Texas—show Republican wins, with the largest in Texas, at a -6.6 D-R margin.

The second simulation—which assumes increased women’s turnout—increases the D-R margin in all states but only flips one formerly Republican win to a Democratic one (North Carolina). In contrast, the third simulation, which also assumes increased female support for Democrats, flips all of the states except one (Texas) to a Democratic victory.

In short, these simulations demonstrate that when assuming actual eligible voter populations as a base, increased women’s turnout and Democratic voting can move several battleground states from a Republican to Democratic advantage.

WHAT THE WOMEN’S VOTE MEANS FOR 2022 AND THE FUTURE

The simulations conducted here make plain that women’s enthusiasm for an issue like abortion can lead to consequential shifts in election outcomes through increases in their voter turnout and support for candidates. This can especially benefit Democrats, given the recent history of women’s support for that party’s candidates in national and congressional elections. Unlike looking at polls alone, simulations such as these show how taking into account the actual eligible voter base and turnout rates can affect election results.

These simulations should not be viewed as predictions, as the actual voting behavior will only be known after Election Day. But they do show how, when translated into voter turnout and voting preferences, an energized voting bloc can impact the final election result. They also show that the women’s vote can have a powerful impact on elections not just in 2022 but also in the future. (William H. Frey, Senior Fellow – Brookings Metro)

This analysis places these estimates in the context of recent decades’ trends, when America’s big cities experienced noticeable ups and downs. It then shifts the focus to the suburbs of major metropolitan areas, which—while benefitting somewhat from recent city population losses—tend to display growth slowdowns of their own.

This analysis places these estimates in the context of recent decades’ trends, when America’s big cities experienced noticeable ups and downs. It then shifts the focus to the suburbs of major metropolitan areas, which—while benefitting somewhat from recent city population losses—tend to display growth slowdowns of their own.

While COVID-19 clearly played a role in this near-zero population growth, that growth had begun to plummet even before the pandemic. The 2020 census showed that from 2010 to 2020, the U.S. registered the

While COVID-19 clearly played a role in this near-zero population growth, that growth had begun to plummet even before the pandemic. The 2020 census showed that from 2010 to 2020, the U.S. registered the