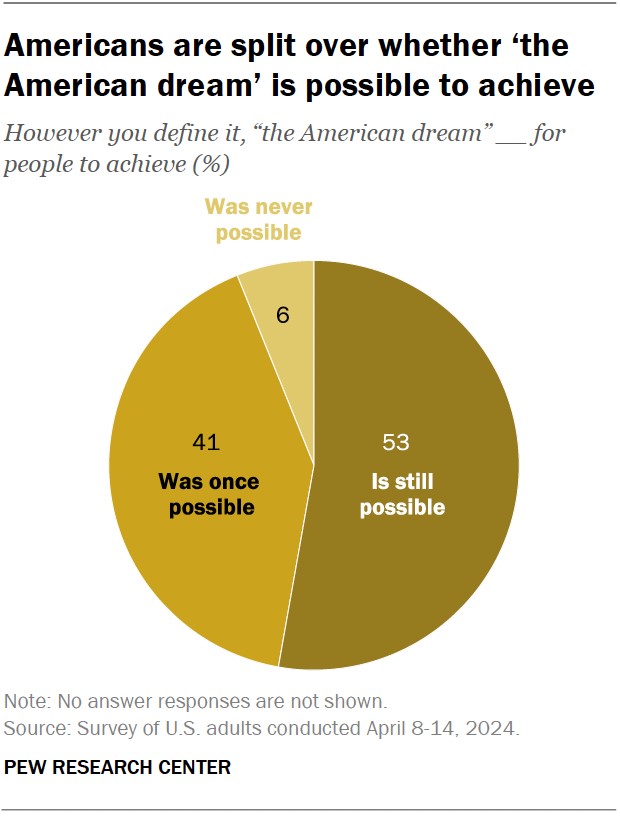

“The American dream” is a century-old phrase used to describe the idea that anyone can achieve success in the United States through hard work and determination. Today, about half of Americans (53%) say that dream is still possible.

How we did this

Another 41% say the American dream was once possible for people to achieve – but is not anymore. And 6% say it was never possible, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey of 8,709 U.S. adults.

While this is the first time the Center has asked about the American dream in this way, other surveys have long found that sizable shares of Americans are skeptical about the future of the American dream.

Who believes the American dream is still possible?

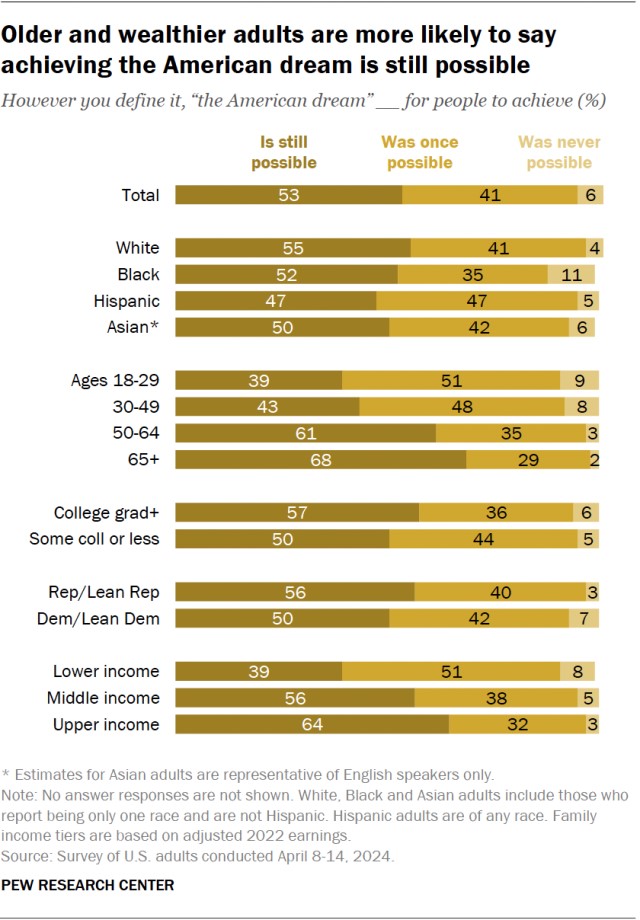

There are relatively modest differences in views of the American dream by race and ethnicity, partisanship, and education. But there are wider divides by age and income.

Age

Americans ages 50 and older are more likely than younger adults to say the American dream is still possible. About two-thirds of adults ages 65 and older (68%) say this, as do 61% of those 50 to 64.

By comparison, only about four-in-ten adults under 50 (42%) say it’s still possible for people to achieve the American dream.

dream.

Income

Higher-income Americans are also more likely than others to say the American dream is still achievable.

While 64% of upper-income Americans say the American dream still exists, 39% of lower-income Americans say the same – a gap of 25 percentage points.

Middle-income Americans fall in between, with a 56% majority saying the American dream is still possible.

Race and ethnicity

Roughly half of Americans in each racial and ethnic group say the American dream remains possible. And while relatively few Americans – just 6% overall – say that the American dream was never possible, Black Americans are about twice as likely as those in other groups to say this (11%).

Partisanship

While 56% of Republicans and Republican leaners say the American dream is still possible to achieve, 50% of Democrats and Democratic leaners say the same.

Education

A 57% majority of adults with a bachelor’s degree or more education say the American dream remains possible, compared with 50% of those with less education.

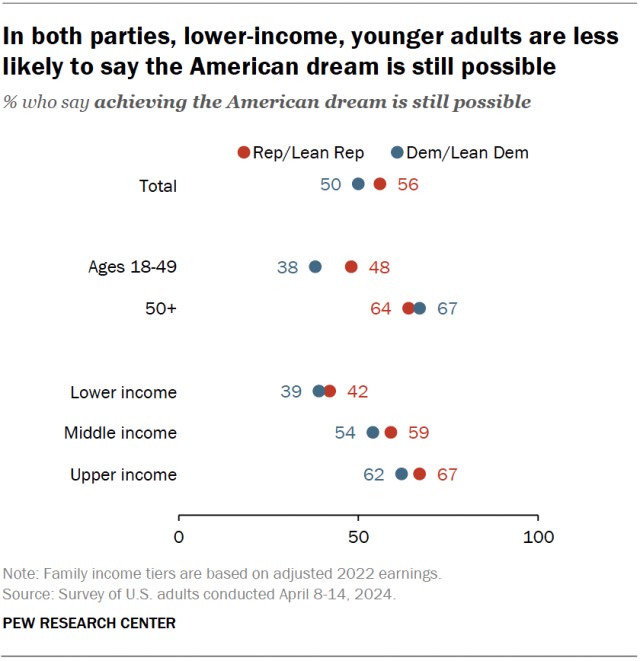

Age and income differences within both parties

Age and income differences in views of the American dream persist within each political party.

Age and income differences in views of the American dream persist within each political party.

Age

Clear majorities of both Republicans (64%) and Democrats (67%) ages 50 and older say achieving the American dream is still possible.

In contrast, just 38% of Democrats under 50 and 48% of Republicans under 50 view the American dream as still possible.

Income

In both parties, upper-income Americans are about 25 points more likely than lower-income Americans to say it is still possible for people to achieve the American dream.

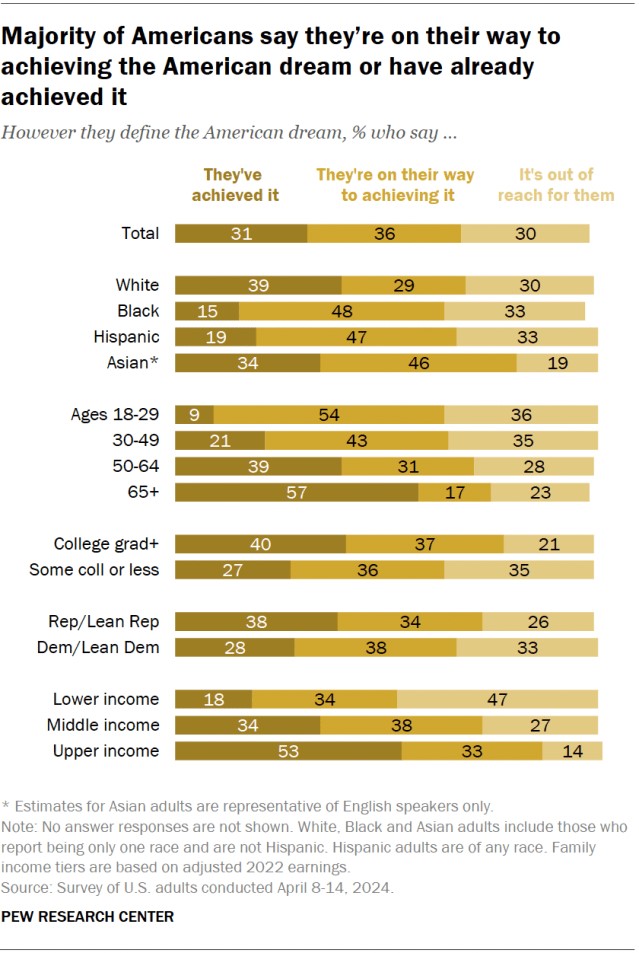

Do people think they can achieve the American dream?

Americans are also divided over whether they think they personally can achieve the American dream. About three-in-ten (31%) say they’ve achieved it, while a slightly larger share (36%) say they are on their way to achieving it. Another 30% say it’s out of reach for them. These views are nearly identical to when the Center last asked this question in 2022.

Race and ethnicity

White adults (39%) are more likely than Black (15%) and Hispanic adults (19%), and about as likely as Asian adults (34%), to say they have already achieved the American dream.

Black (48%), Hispanic (47%) and Asian adults (46%) are more likely than White adults (29%) to say they are on their way to achieving it.

Party

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say they have achieved the American dream (38% vs. 28%). But Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say they’re on the way to achieving it (38% vs. 34%). Democrats are also more likely than Republicans to view the American dream as personally out of reach.

Income and age

Older and higher-income Americans are more likely than younger and less wealthy Americans to say they have achieved or are within reach of the American dream. These patterns are similar to those for views about the American dream more generally.