Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption has long been associated with better heart health, but the exact reasons behind this connection have remained a mystery. Despite the well-known health risks associated with alcohol, including a higher risk of cancer and neurological aging, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital have shed light on one potential explanation. Their recent study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, reveals that alcohol may reduce stress signals in the brain, resulting in less strain on the heart.

To unravel this phenomenon, scientists delved into data from over 50,000 individuals from the Mass General Brigham Biobank, a comprehensive research database. Their findings confirmed that light-to-moderate drinking was indeed linked to a significant reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease. Importantly, the extensive scale of this study enabled them to rule out external factors such as socioeconomic status, physical activity, and genetics that often complicate smaller-scale research. It became evident that something unique was at play, a discovery further illuminated by examining participants’ brain scans.

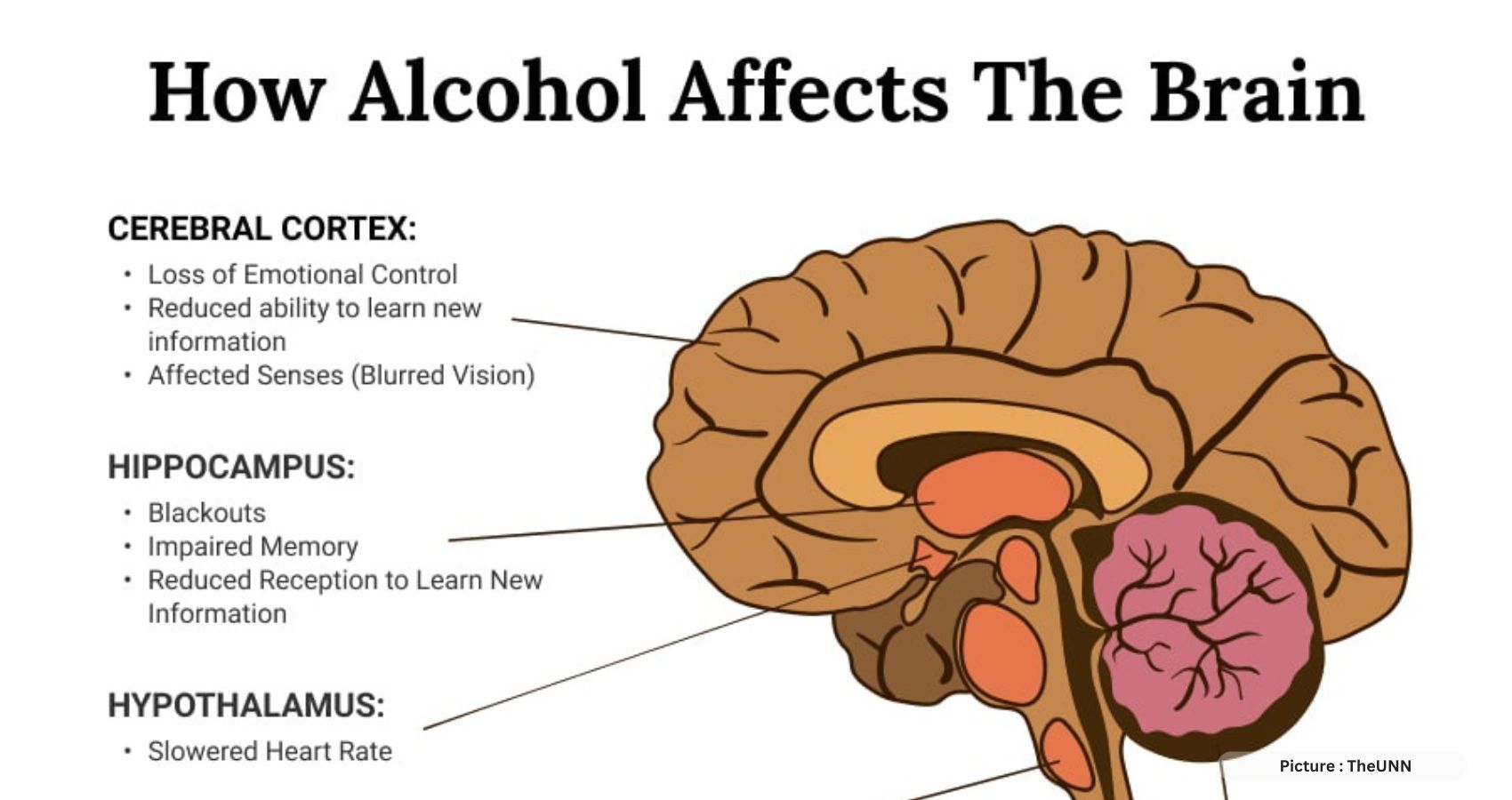

These brain scans revealed that alcohol could have enduring effects on stress levels within the brain, subsequently relieving the heart from excessive burdens, even days after the last drink. The brain’s stress network is akin to a tug-of-war, with the amygdala, responsible for emotions, on one side, and the prefrontal cortex, governing executive functions, on the other. During stressful situations, the amygdala sends distress signals, while the prefrontal cortex can inhibit the amplification of this alarm throughout the body, including the heart.

Dr. Ahmed Tawakol, a study author and co-director of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, noted that alcohol is known to alleviate the amygdala’s alarm response. However, the researchers posed a unique question: does it exert long-term effects on these systems? Analyzing brain scans from over 1,000 study participants, they discovered that light-to-moderate drinkers experienced sustained reductions in amygdala activity, with prefrontal cortex activity remaining unaffected when alcohol was not in their systems. While the data did not allow researchers to determine whether this effect on the amygdala would diminish if individuals ceased drinking altogether, this dampening of amygdala activity was associated with a notable 22% decrease in cardiovascular disease risk.

Dr. Ahmed Tawakol, a study author and co-director of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, noted that alcohol is known to alleviate the amygdala’s alarm response. However, the researchers posed a unique question: does it exert long-term effects on these systems? Analyzing brain scans from over 1,000 study participants, they discovered that light-to-moderate drinkers experienced sustained reductions in amygdala activity, with prefrontal cortex activity remaining unaffected when alcohol was not in their systems. While the data did not allow researchers to determine whether this effect on the amygdala would diminish if individuals ceased drinking altogether, this dampening of amygdala activity was associated with a notable 22% decrease in cardiovascular disease risk.

Moreover, when the researchers specifically examined light-to-moderate drinkers with a history of anxiety, characterized by an overactive stress network, they observed a doubling of the effect. Dr. Tawakol explained, “Rather than the 22% reduction, people with prior anxiety had a 40% reduction in heart disease.” However, he emphasized, “I know that a lot of people will hear that and say, ‘Well, I’m anxious. That’s why I drink—I guess there’s a benefit.’ But there is no safe quantity of alcohol.”

While these findings are intriguing, Dr. Tawakol highlighted that there are alternative, safer ways to tap into this stress-reducing pathway. Exercise, for instance, is currently being studied by Tawakol and has been shown to increase prefrontal cortex activity, achieving similar stress-reduction benefits. Adequate sleep, too, operates along similar lines. Dr. Tawakol’s ultimate objective, however, is to identify pharmacological interventions that can safely diminish amygdala activity. He stressed the need to move beyond conventional recommendations like “get more sleep and exercise” in light of this newfound pathway that, when targeted, can double the reduction in cardiovascular disease risk.