Parul Kapur’s debut novel, *Inside the Mirror*, explores the lives of twin sisters in post-independence Bombay, weaving themes of art, ambition, and the enduring impact of Partition.

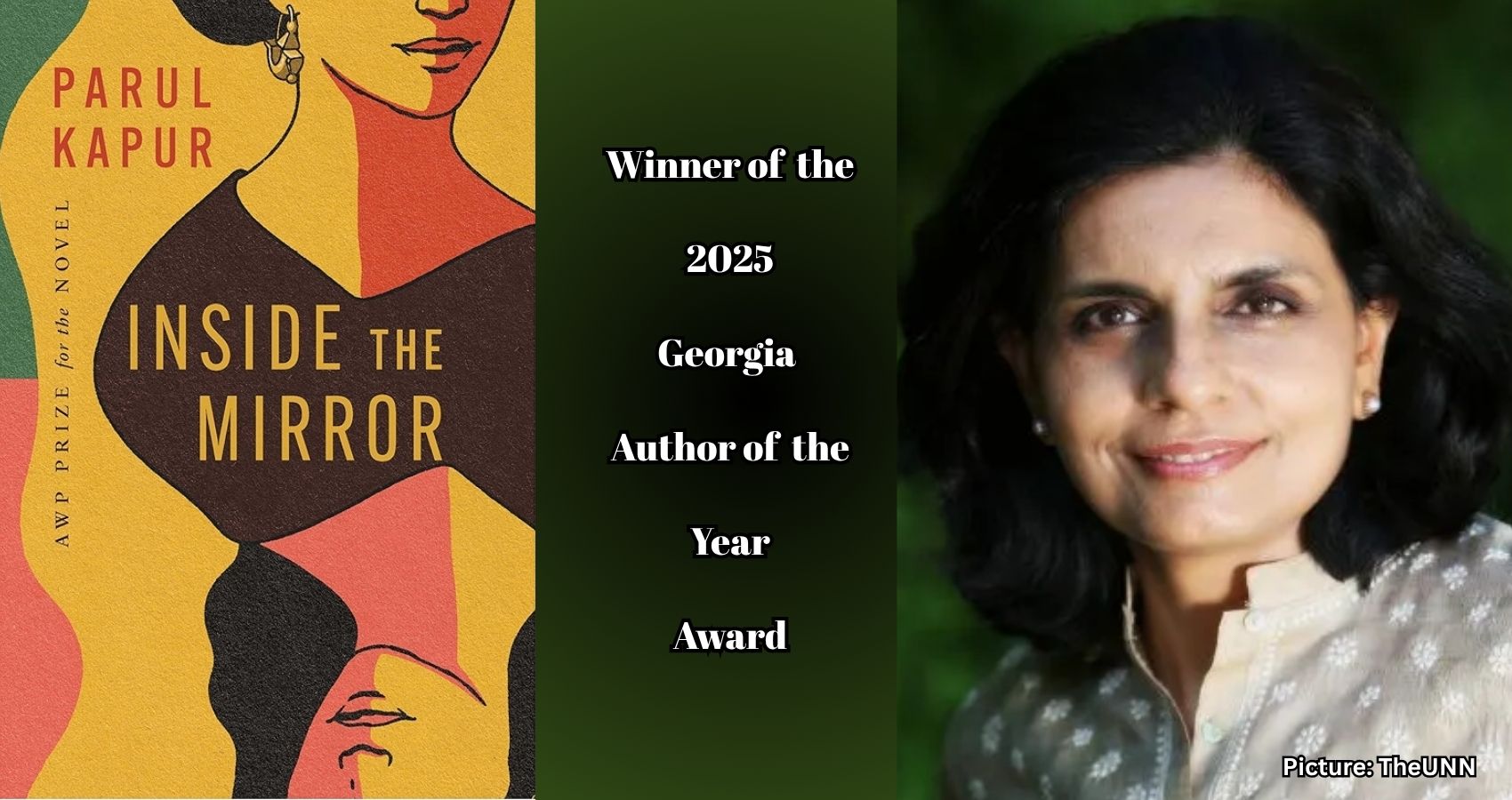

Parul Kapur’s debut novel, *Inside the Mirror*, has garnered significant acclaim, winning the 2025 Georgia Author of the Year Award in the first novel category and the 2024 AWP Prize. Set against the backdrop of post-independence Bombay, the narrative follows twin sisters Jaya and Kamlesh Malhotra as they navigate the complexities of their lives shaped by the traumas of Partition and the expectations of their Punjabi Khatri refugee family from Chiniot, now in Pakistan.

Reading *Inside the Mirror* evokes a sense of serendipity, as if stepping into a parallel life. The novel resonates with vivid memories of medical training in Bombay and a longing for artistic expression. Jaya, a medical student with a passion for painting, mirrors the author’s own experiences, while Kamlesh, studying at Sophia College, excels in Bharat Natyam and dreams of an acting career. Their father, Harbans, views these aspirations as respectable and safe, suitable for marrying into a “nice” Punjabi family, relegating art to the status of a mere pastime.

Jaya’s character struck a deep chord with me. While I found the formaldehyde in dissection halls off-putting and dreaded carrying my satchel of bones on crowded buses, Jaya drew inspiration from her surroundings. She painted patients, factory workers, and cadavers in a Fauvist style influenced by artists like Rouault and Derain. However, her artistic expression ultimately led to scandal and her expulsion from medical school. Jaya’s study of human anatomy not only enriched her art but also highlighted the tension between her passion and the societal expectations that sought to stifle it.

The novel intricately explores themes of inheritance and ambition, with the grief of Partition ever-present. Kapur captures the essence of Punjabi domestic life with remarkable precision: the Arya Samaji culture, whispered conversations over tea and cucumber sandwiches, and the gentle clinking of china in sunlit rooms. Harbans, the father, evokes memories of my own principled and protective father, while Vidya, the mother, with her elegant sarees and pearls, reflects my mother’s grace. The scandalized Punjabi aunties, oblivious to their Mesopotamian heritage, are strikingly familiar figures.

The shared bedroom of the twins, divided by a curio cabinet, serves as a poignant metaphor for intimacy and separation. I, too, shared a room with my sister in a household that encouraged the arts but never regarded them as viable careers. Like Kamlesh, my sister was inclined toward music and dance, and our father, much like theirs, kept us away from Bombay’s entertainment world, wary of its instability and dangers for girls from “good” homes.

Kapur’s descriptions are rich and cinematic, bringing to life Jaya’s portrait of Heerabai, the family maid, adorned with vine-like tattoos, and her bond with Sringara, the only other female member of the fictional Group 47, who wears a bold bindi against austere widow’s whites. Kamlesh’s arangetram in Matunga is depicted with grace and beauty, reminiscent of performances I attended at Shanmukhananda Hall.

Among the most influential figures in the twins’ lives is Nihal Devi, their grandmother. Her frail frame belies a fierce spirit, transforming from a despondent elder into an activist who secures essential resources for shantytown workers on the Thana-Belapur Road. She embodies both history and resistance, bridging the past and future in a way that foreshadows her granddaughters’ independent intellect. The twins are accepted by their family for their intellect, resilience, and creative strength, rather than for conformity.

Kapur captures the rawness of sisterhood, with its secrets, conflicts, wounded egos, and eventual reconciliation. In a brief conversation, she shared that the novel developed over decades. A graduate of Columbia’s MFA program, she began with short stories, later weaving them into a novel after her experiences as a journalist in Bombay.

Her research included interviews with doctors, artists, and members of the Progressive Artists’ Group, as well as insights from her father, who fled Lahore during Partition. This background lends the work a layered authenticity. The fictional Group 47 pays tribute to the Progressive Artists’ Group founded in 1947. Like Amrita Sher-Gil, Jaya seeks not only to create art but to claim a self shaped by history yet unbound by it. As one character observes, “All art is history.”

*Inside the Mirror* serves as a shared history, animated not by dates but by desire, conflict, and the journey of becoming. Its non-linear structure mirrors the nature of memory—fractured, looping, and intimate—producing a portrait of a family, a city, and two young women resisting the roles assigned to them. For those who came of age in India after Partition, this novel acts as a time capsule, reminding readers of what has changed and what endures. It is a lush, nuanced, and quietly powerful work that lingers like a painting long after the gallery lights have dimmed.

Source: Original article