Queens Borough in New York City is known as “The World’s Borough” for a reason: what happens on Roosevelt Avenue has ripple effects near and far.

In this vibrant borough there is a street called Roosevelt Avenue that cuts a cross-section through some of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods on Earth. Spanish, Bengali, Punjabi, Mixtec, Seke, and Kuranko are among the hundreds of languages spoken here. Nepalese dumplings and Korean noodles, Mexican tortas and Colombian empanadas, Thai curries and spicy South Indian vindaloos are just some of the many food choices.

Passing from one block to the next—through neighborhoods including Elmhurst, Corona, and Jackson Heights—can feel like crossing continents. Plazas and parks are crowded with vendors selling tamales, atole, and large-kernel corn. Tibetan Buddhists, fluent in the Indigenous languages of the Himalayas, walk to worship in their red-and-orange robes. Bangladeshi curbside markets teem with overflowing crates of ginger, garlic and humongous jackfruits, picked out by people wearing saris and shalwar kameez.

Growing up in New York, my own family would come to Queens to watch World Cup matches in South American cafés, just as our abuelos would visit their trusted Argentine butcher for fresh cuts of meat, and our Bukharan Jewish neighbors would come to pray, and our Indian family friends would come shopping for amulets and syrup-drizzled sweets for celebrations, all within this same 10-square-mile stretch of city.

Roosevelt Avenue is a pulsing artery of commerce and life. The road itself is chaotic, dark, and loud. You know you’re on Roosevelt because the elevated 7 train runs overhead, the tracks draping it in slitted shadows, and when the 7 train thunders past, for a moment, the frenzied thoroughfare is consumed: older women look up from their pushcarts; chatting friends fall silent mid-speak; and children cover their ears.

Above the storefronts, at the level of the train, are smaller brick offices with signs that reveal the more pressing needs of such a migrant-rich community: “Sherpa Employment Agency,” “Construction Safety Training,” “Irma Travel: Send Money and Shipments to Lima and Provinces.” Taped to the metal pilings and lampposts are hand-written listings with tear-off phone numbers, mainly in Spanish, advertising “rooms for rent,” “employment needed,” and “help wanted.”

Road signs welcome drivers entering Queens to “The World’s Borough.” But there is another phrase that might be more apt: “Queens, Center of the World.” That’s because what happens on these streets has ripple effects near and far, sometimes as far as on the other side of the globe—and what happens on the other side of the globe also certainly influences who ends up here. Perhaps at no other point has this been more urgently felt than during the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the spring of 2020, the virus ravaged this part of the city. Most people who live here are essential workers who cannot work from home—restaurant cooks, delivery workers, cab drivers, construction builders—and many live in overcrowded quarters, so the disease spread precipitously. Elmhurst Hospital, which serves this community, was declared the “epicenter of the epicenter” for the initial outbreak in the U.S.

In New York, such a rapid and large-scale loss of life meant that the city’s engine sputtered to an even more devastating halt; in other places, like Mexico and Ecuador, Bangladesh and Nepal, it meant that many families could no longer rely on support from relatives in Queens who were suddenly out of work, or worse. Joblessness and hunger skyrocketed, residents just barely getting by. And yet only for a very short while did walking Roosevelt and its surrounding streets have the same eerie, empty feel as in the rest of the city. Its communities and micro-economies, heavily reliant on in-person interactions, cannot afford to stay still.

In New York, such a rapid and large-scale loss of life meant that the city’s engine sputtered to an even more devastating halt; in other places, like Mexico and Ecuador, Bangladesh and Nepal, it meant that many families could no longer rely on support from relatives in Queens who were suddenly out of work, or worse. Joblessness and hunger skyrocketed, residents just barely getting by. And yet only for a very short while did walking Roosevelt and its surrounding streets have the same eerie, empty feel as in the rest of the city. Its communities and micro-economies, heavily reliant on in-person interactions, cannot afford to stay still.

“The people who come over, they come to help their family,” says Sanwar Shamal, of Bengali Money Transfer in Jackson Heights.

Snippets of South Asia

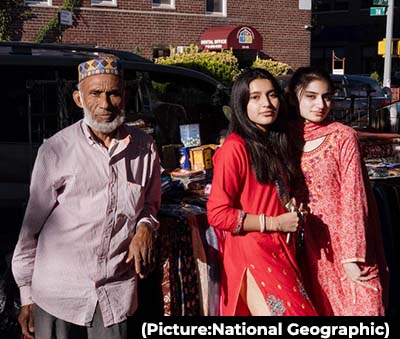

Around the 74th Street subway station, the neighborhood is heavily South Asian—mostly people of Bangladeshi, Indian, and Nepalese origin. Bengali-speaking men wearing skullcaps sell plush prayer rugs, headscarves, and gold-plated Islamic iconography from milk crates on the sidewalks, cigarette smoke pouring out of their mouths as they talk. Mannequins showcase bright-colored salwars and chaniya cholis through tall glass windows, and restaurants serve curries with rice and water in silver bowls and cold metal cups.

Seemingly everywhere in Roosevelt’s path, there is a heightened sense of the “old country”—of memories that haven’t faded over long stretches of distance and time. You feel it in the money-transfer and international courier stores along Diversity Plaza, where people line up patiently to send remittances and packages to relatives back home, relatives they haven’t seen in years and might not ever see again. You feel it on the weekends, when families drive in from all over to shop for groceries at Patel Brothers, or to eat at Samudra or Dera or the famous Jackson Diner. You feel it at the sweet shops, where grandfathers wearing tweed suits and large wristwatches take their smiling grandchildren for treats.

And you certainly feel it when you step into the United Sherpa Association, a former Lutheran Church that in 1996 was converted into a Tibetan Buddhist temple and community center now serving more than 12,000 Himalayan Sherpas, the largest population living outside Nepal. People come here to pray and to drink salty yak-butter tea poured from tall thermoses into bowls of blue-and-white china. In pre-pandemic times—according to Tshering Sherpa, the president of the association—nearly 100 people would fill two floors in this temple to worship. “You could hear the chanting from Broadway,” she says, beaming.

“Our seniors established this United Sherpa Association,” says Temba Sherpa, the group’s vice president, “to protect and maintain our identity.” The Sherpa are a Tibetan ethnic group who for hundreds of years have made their livelihoods in the Himalayas, raising yaks and high-altitude crops in the remote mountains. Practically no one knows the Himalayas better than the Sherpa, and in recent years they’ve also become synonymous with their work as climbing guides and porters on Mount Everest.

“We got our identity and economic benefit from mountaineering,” says Ang Tshering Sherpa, himself a former trekking guide. “But there’s not much of an alternative if you aren’t educated.”

Climbing is often a perilous endeavor for the Sherpa, especially with little in the way of formalized protections from the turbulent Nepalese government. “Going to the mountains, it’s like going to war,” Ang Tshering says. “You don’t know if you’ll come back.” Many hundreds of Sherpa people have died or been seriously disabled on climbs over the years. “Once a Sherpa gets in a kind of accident, the family gets very little, they don’t have a safety net,” Ang Tshering adds.

Since the 1990s, and especially after major climbing disasters on Everest, Sherpa have left Nepal in large numbers. Many have come to the area around Roosevelt Avenue, where they often work as taxi drivers, or restaurant cooks and supermarket employees. The United Sherpa Association is a central meeting point of worship and community—where people chant and pray, gather for meals of dhal and root-vegetable stews, and share opportunities for work or study.

Since the 1990s, and especially after major climbing disasters on Everest, Sherpa have left Nepal in large numbers. Many have come to the area around Roosevelt Avenue, where they often work as taxi drivers, or restaurant cooks and supermarket employees. The United Sherpa Association is a central meeting point of worship and community—where people chant and pray, gather for meals of dhal and root-vegetable stews, and share opportunities for work or study.

There are also classes to teach the Sherpa language and traditions to new generations born in the U.S. Shortly after the pandemic began, the association opened a food pantry—available not only to Sherpas but to anyone—and every Tuesday since then, people have lined up in need. And the Sherpas haven’t stopped advocating for their family members back in Nepal, either: for better educational and economic opportunities, and for improved safety infrastructure for climbing guides and porters, especially as recent tourism downturns and pandemic outbreaks have further devastated the country.

“Most of the Sherpa over here, their families are still in Nepal,” says Pasang Sherpa, president of the US-Nepal Climbers Association, a Queens-based nonprofit. “We know exactly who needs help.”

‘La Roosevelt’

Down the road, the sound of spoken Spanish envelops either side of what’s known as ‘La Roosevelt.’ In Jackson Heights there is a block nicknamed ‘Calle Colombia’ (Colombia Street)—where vendors slice cold coconuts with machetes, and tall stalks of sugarcane disappear into juicers for the sweet drink called guarapo. Further east are standing-room-only taquerias, stores bursting with knock-off soccer jerseys, and electronics dealers and barber shops with hawkers outside telling passersby to come in, just for a minute, just to take a look.

On 80th Street, just south of Roosevelt in Elmhurst, Barco de Papel (Paper Boat) stands as the sole Spanish-language bookstore left in New York City. One of the owners is an older Cuban man named Ramón Caraballo who can usually be found there smoking a cigar. He speaks softly and sparingly. “I am just a man who opens up a bookstore in the morning and closes it at night,” Caraballo said when he first introduced himself. “That is all.”

The building is small, just one room, but it is filled from floor to ceiling with a large selection of some of Latin America’s finest writers—Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende—as well as lesser-known staff favorites. It is so stuffed with books only its keepers know where anything is to be found.

Caraballo is one of those keepers. Before he co-founded Barco de Papel in 2003, he sold books from a street cart around the corner. “All my life I’ve dedicated myself to literature,” he says. When he opened the nonprofit store—around the same time that Amazon and rising rents began to spell the demise of independent bookstores, especially Spanish-language ones, across the U.S.—it quickly became a community treasure.

Many customers come to Barco de Papel hoping to rebuild the libraries they left behind when they migrated. “They bring their kids, too,” says Paula Ortiz, a high school teacher from Colombia who co-founded the store. “They can’t take them to their countries, so they bring them here.” Others will gather for tertulias—discussions about literature and current events—and live readings.

But Barco de Papel has also become a hub for information. Since the pandemic, many customers leave with information on vaccines, testing, or treatment. New migrants seek out guidance on how to start a small business or learn English. Children whose parents can’t afford to buy another book benefit from book exchanges.

“We have to constantly change with the community, without losing our essence,” Ortiz says. “We owe ourselves to them.”

Corona Plaza

One afternoon in Barco de Papel, I found Caraballo and two helpers unwrapping a large painting that they were planning to put up in a nearby underpass, part of a public art installation in homage to the neighborhood. This one was a bright-colored portrait of a Latina street vendor flanked by a food truck and some ears of large-kernel corn.

Street vending has long been woven into the fabric of Queens, where on the sidewalks you can buy just about anything. In largely Chinese and Korean neighborhoods like Flushing, vendors pull steaming dumplings and salted duck eggs out of steel tubs; plastic bins offer spiced watermelon seeds, eyebrow beans, and goji berry soup. Along Roosevelt, Bangladeshis and Afghans peddling religious items cross paths with Spanish-speaking vendors who sell food and drink, small metal lockets and neon construction vests, disposable masks, rat poison, smartphone cases, and flowered hanging plants.

Some have been selling for years. Many others have only recently begun, after losing their jobs because of the pandemic-induced economic crisis. Pop-up stands of folding tables and tents have appeared (and expanded) on much-transited corners. People walk past with strollers, pulling back the top to reveal not children but candies, popsicles, and sandwiches. Women weave their way through traffic carrying months-old babies in slings on their backs, selling sliced fruit to drivers at red lights.

“Vending has always been big along Roosevelt, especially in Jackson Heights and Corona, but even more so now, because so many people have lost their income, are facing eviction, and have no safety net,” says Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez, deputy director of The Street Vendor Project, a nonprofit that works with street-sellers across New York City. “Every type of relief that came out during the pandemic excluded undocumented folks. And that hit the area so especially hard.”

The Street Vendor Project estimates that during the pandemic, the number of vendors in Corona Plaza, along Roosevelt Avenue at 103rd Street, rose nearly fourfold, from 20-30 people to more than 100. They come prepared for the elements—with tents, tarps, umbrellas and plastic garbage bags—and work through the rain, snow, sun, and cold.

“We used to live in the mountains, my family,” says María Lucrecia Armira, 44, who migrated to Queens in 2019 from a small village in the department of Suchitepéquez, Guatemala. She has had to adjust to spending nearly every waking hour in the smoky heat of a grill stand, selling meat skewers on the loudest corner of the Plaza. Armira arrived two years ago with her 14-year-old son, who enrolled in the local public school; when the pandemic began a short time later, he dropped out and started working full-time selling raspados (shaved ice) and slushies.

“On the one hand I was nervous about the virus,” Armira says. “On the other hand, we were locked down and couldn’t work.” Sharing a single bedroom with her son in an apartment filled with other families, she tries to send $500 per month—or whatever she can—to her two other children, whom she had to leave behind in Guatemala. “Many people count on what we send from here.”

Street vendors now face opposition from brick-and-mortar business owners frustrated with the sudden boom in new and seemingly unlimited competition. In recent months, the city has stepped up its enforcement of street-vending laws, ticketing and removing those without a permit. There are more than 20,000 vendors estimated to be working in the city, and just a small fraction of permits, leading to price-gauging, according to labor activists.

One afternoon on Corona Plaza, the presence of two New York City inspectors sent many vendors scurrying. There were fewer produce-sellers on the sidewalk, food trucks were shuttered, and shopping carts stood empty, piled atop each other beneath the train tracks.

Ana Maldonado stood nervously in the shadows—across the street from her usual spot on the plaza, where for more than 15 years she’s sold tamales and rice pudding and syrupy Mexican-style hot chocolate from a cart of metal vats and orange Gatorade thermoses.

“My customers know me, they know where to find me,” she says, looking out for inspectors from the stairs to the train. The inspectors had warned her to leave, or risk an expensive fine and all of her merchandise being tossed to the trash. “They’re in the middle of the plaza. If they catch me, I’m finished.”

Originally from a small mountain town in Guerrero, Mexico—where, in the green hills, steam rises from rivers swelled with rain—now she wakes up each morning at 4 a.m. and prepares the day’s food for sale on Roosevelt, not returning home until she’s sold everything. Her husband spent 28 days in the hospital with COVID-19 at the start of 2020 and nearly died; he has been unemployed since. “All that my family has, everything comes from this,” Maldonado says. “I work hard to feed them, whatever it takes.”

Queens Globe

As Roosevelt Avenue nears the end of its eastward course, it’s fitting that it passes by the famous Unisphere, the Queens Globe built for the 1964 World’s Fair, that has since become a symbol of this area’s epic cultural diversity. Here in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the hustling chaos of Roosevelt Avenue abates, if only for a moment, and the world’s borough comes outside to decompress.

In springtime, families take pictures at golden hour in their best sunshine saris, their favorite skirts and collared shirts in front of an explosion of color: the cornelian cherries, the flowering pears, the forsythia and the redbuds in full bloom. Two years after the onset of the pandemic, despite all the challenges the coronavirus has left behind, there are signs of renewal, too—of soccer games returning to dusty fields with goals carried on backs and bicycles; of misting fountains, and the smell of new grass; of the sound of Mister Softee trucks offering ice cream to children with outstretched arms.

I have often thought about what it means to be American on my walks along Roosevelt—what it means to be the product of so many different stories and struggles and heritages that have led us to one singular, raucous mix of a place. In this country that so deeply strives for assimilation, there is often pressure to distill identities, to make them more palatable for others looking on.

But what is both so special and so hard about Queens is that assimilation does not come easy.

I think about this with every scene that crosses my gaze, with every encounter and conversation—whether in a bookstore or a temple, on the 7 train or on a soccer field in the park. I think about the many definitions of “American” when my own family, a blend of cultures shaped by migrations forced and voluntary, ventures out to this neighborhood for tastes of a past that continues to mark our future here. As parents look for fair and just opportunities to raise their children in the U.S., to learn English, to find work, and to support their families abroad, that sense of the ‘old country’ is unlikely to fade from Roosevelt Avenue, so long as people keep migrating to neighborhoods like this one.

I thought about that when I first met Maldonado, the undocumented street vendor who left Mexico two decades ago and cannot return without risk of not being able to get back into the U.S. I told her that I’d recently been there and asked her what part of the country she was from. Instead of answering right away she touched my wrist with her hands and looked into my eyes. “Cómo está?” she asked about her homeland. “How is it?”