After the latest massacre in America — this time in an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, in which 19 children and two adults were killed — Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., vowed his chamber would again take up legislation to address gun violence despite Republican opponents arguing the regulations are misguided.

Congress’ current divide on the issue is deeply rooted, tracing back to the mid-1990s, and has been shaped by electoral politics including the Democratic rout in the 1994 midterms that saw them lose the House for the first time in 40 years.

While Democratic lawmakers have at various times urged more federal gun reforms — mostly focused on assault-style or military-grade weapons and munitions and expanding the screening process for who can and cannot have a gun — Republicans say the focus should be elsewhere, on increasing public security and awareness of mental health and social issues.

Still the shootings continue, with new rounds of legislation often proposed in the wake of the worst killings: in Uvalde and in a Newtown, Connecticut, elementary school a decade earlier; and at Columbine High School 13 years before that, among other examples.

The prospect of a new federal law appears at the least very uncertain, given the partisan split. But legislators on both sides of the aisle are again talking, led by Connecticut Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy. Areas of focus and possible agreement include expanding background checks on gun sales — which has been voted down in Congress multiple times — and so-called “red” and “yellow flag” laws that would prevent someone from possessing a firearm if they have certain histories of concerning behavior.

Here is a look back at notable pieces of federal gun legislation that either passed or were defeated in Congress. The timeline reflects in part how the politics around guns, and the coalitions of politicians focusing on it, have shifted over time — from anxieties about crime in the ’90s that drew bipartisan backing to major support for gun manufacturers in the early 2000s to outcry about reducing school killings, and beyond.

2021: The House Democratic majority passes two lightly bipartisan measures expanding background checks, despite Republicans reiterating objections on Second Amendment grounds. One bill increases the window for review on a sale from three to 10 business days; the other bill essentially requires background checks on all transactions by barring the sale or transfer of firearms by non-federally licensed entities (closing so-called private loopholes). House Democrats vote to approve the first bill along with two Republicans (and two Democrats voting no). All Democrats except for one along with eight Republicans vote yes on the second bill, which previously passed the House in 2019, also under Democratic control.

2018: Congress passes and President Donald Trump signs into law an incremental boost to the federal background check system for potential gun owners. (The legislation is included as part of a necessary government spending package approved by wide bipartisan margins.)

2017: Trump signs into law a congressional reversal of an Obama-era rule which would have added an estimated 75,000 people to the federal background check system who were receiving Social Security mental disability benefits through a representative. Republican majorities in the House and Senate are joined by a few Democrats — four in the Senate and and six in the House — in blocking the impending regulation, which is opposed by both civil liberties and gun rights advocates.

2017: The House Republican majority is joined by six Democrats — with 14 Republicans opposing, arguing federal overreach — in backing a measure expanding concealed carry permits across the country via a reciprocity law requiring states to honor permits issued elsewhere. The bill dies in the Senate.

2013-2016: Partially prompted by the Sandy Hook Elementary School and Pulse nightclub killings, Congress takes up and then votes down various measures to expand background checks for sales online and at gun shows and to block people on no-fly and terrorism watch lists from being able to buy firearms. In one representative set of votes, in 2016, Democratic and Republican senators (with Republicans in the majority) each advance two proposals that are blocked along party lines. While some of those measures garner a majority, none get the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster as a potential winning compromise is frayed by differences over tactics and approach. Still, Susan Collins, R-Maine, reiterates hope — somewhere down the line — citing “tremendous interest from both sides of the aisle.”

2013: A bipartisan group in the Senate fails to approve their own expansion of concealed carry permits across the country, similar to what the House later takes up in 2017 and earlier tries to pass in 2011. Republicans, then in the minority, are joined by 12 Democrats — many of whom later say they oppose the expansion as the party and its base recommits to messaging around reducing guns and shootings.

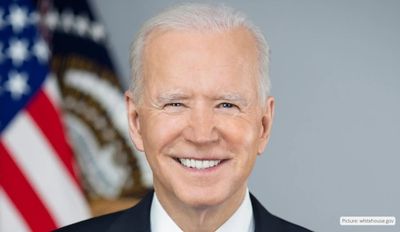

2005: Congress’ Republican majority is joined by dozens of Democrats in passing the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms, signed into law by President George W. Bush. The legislation shields gun manufacturers from legal liability in almost all instances where their firearms are criminally used — with exceptions for defects in gun design, breach of contract and negligence. (PLCAA has since become a major target of Democratic ire, singled out by President Joe Biden, though such protections are not unheard of for other industries.)

1999: Previewing failed efforts to come, Congress votes down legislation to institute background checks and waiting periods for purchases at gun shows.

1994: In what would become the last major piece of federal gun legislation enacted by Congress, the Federal Assault Weapons Ban bars the manufacture and possession of a broad swath of semiautomatic weapons. The provision is included as part of the sweeping 1994 crime bill, shepherded by then-Sen. Biden and signed into law by President Bill Clinton. Gun legislation in this era is politically intertwined with federal efforts to curb crime. While the House narrowly passes the assault ban on its own and then later, successfully, via the overall crime legislation — in the first case, with most of the Democratic majority being joined by 38 Republicans; later, along with 46 Republicans — the crime bill is approved overwhelmingly in the Senate, with only two Democrats and two Republicans voting against and one Democrat, North Dakota’s Byron L. Dorgan, abstaining. The Senate approves with slimmer margins a reconciled version with the House in late 1994, with seven Republicans joining the Democratic majority. Clinton signs it shortly after. The assault ban includes some exemptions on the outlawed weapons along with a sunset date after 10 years, in what were seen as necessary concessions. Subsequent efforts to reauthorize the ban have failed.

1993: A year before the assault weapon ban, and amid sharp public concern about street-level crime, the House and Senate back the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (named for President Ronald Reagan’s press secretary James Brady, who was gravely wounded in Reagan’s attempted assassination in 1981). Commonly known as the Brady bill, it institutes background checks for federally licensed sellers and initially imposes a five-day waiting period on sales — a provision that is later sunset with the launch of the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. Two-thirds of House Democrats are joined by a third of House Republicans in voting yes on the legislation. Although eight Democratic senators vote no (and one abstains), 16 Senate Republicans approve its passage along with the Democratic majority. President Clinton signs it into law.