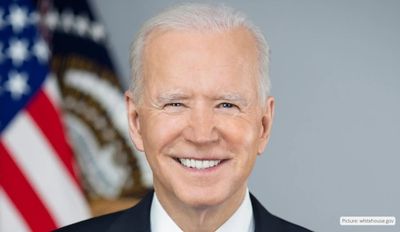

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the United States last month looked more like a goodwill gesture than a business trip, a number of experts told the media. Beyond the optics, they pointed out, there was much work to do to bring the two countries closer. In Washington DC where he stayed for three days, Modi maintained an uncharacteristically low profile. He met President Joe Biden, a handful of CEOs, leaders from Japan and Australia and adopted one-on-one meetings. Despite the photo-ops and the invites and long walks, some uncomfortable questions propped up their heads.

“I hope his White House visit includes honest conversations about how the Modi government can ensure India’s democracy remains a democracy for all of its people,” said US Representative Andy Levin (Democrat, Michigan). Others pointed to Biden and Harris stressing on threats to democracy globally and underlining the values of Mahatma Gandhi. In the realm of trade and economy, too, Silicon Valley voices were not exuberant in their praise of the visit. A number of them pointed out that India currently has no trade agreement with the United States of America.

“I hope his White House visit includes honest conversations about how the Modi government can ensure India’s democracy remains a democracy for all of its people,” said US Representative Andy Levin (Democrat, Michigan). Others pointed to Biden and Harris stressing on threats to democracy globally and underlining the values of Mahatma Gandhi. In the realm of trade and economy, too, Silicon Valley voices were not exuberant in their praise of the visit. A number of them pointed out that India currently has no trade agreement with the United States of America.

In April 2018, the United States launched an eligibility review of India’s compliance with the General System of Preferences (GSP) market access criterion. In March 2019, it was decided that India no longer meets the GSP eligibility criteria and India’s GSP status was revoked. Termination of GSP benefits removed special duty treatment for $5.6 billion of exports to the US, particularly affecting India’s export-oriented sectors such as pharmaceuticals, textiles, agricultural products, and automotive parts. The United States and India continue holding discussions to address trade issues and to prepare a limited trade deal. Kanwal Rekhi, founder and managing director, Inventus Capital Partners said the sudden rise of China has put India in an awkward position.

“China is five times the size of India and has spent lavishly building its military,” Rekhi pointed out. “India is unable to match that. China and India have a 2100 mile unsettled border and China has toyed with India from time to time and uses Pakistan to pin India down. India needs time to build its economy to stand up to China. India does have nuclear capability and as such ultimate security. India needs Quad to balance China and the US needs a heftier partner than Japan to take on China. The moment is right and it is imperative that India overcome its traditional hesitancy and form a firmer partnership to maintain its independence.”

Vish Mishra, venture director at Clearstone Venture Partners, said in his view the main purpose of this visit was to build goodwill with President Joe Biden who is a bit more reserved than his predecessors Donald Trump and Barack Obama. Mishra said he was expecting more, beyond the optics such as Modi citing Harris’s India heritage and inviting her to visit India. “Given that there have been many advance visits by the US defense and commerce Secretaries as well as Mr Kerry to India, leading up to Mr Modi visit, I would surmise that the security and trade dialogs are on-going. And I did not see any agreements or MoUs being signed,” Mishra pointed out. “What I really find missing is US not appointing its new ambassador to India. Hopefully this will happen post Modi’s visit,” Mishra said.

He pointed out that Modi’s meeting with the five CEOs represented five major sectors critical to India. Adobe for technology, Qualcomm for 5G, General Atomics for energy and space, First Solar for renewal energy, and Blackstone for Capital investment.

“They all look at India favorably and are doing business there already,” Mishra said. “From my observations, Stephen Schwarzman, Blackstone’s CEO, turned out to be the biggest champion and booster for India. He was unabashed in his praise for India, declaring that he has already invested $60 billion in India and plans to another $40 billion in the near term. Shantanu Narayen, the Adobe CEO, was equally bullish about India, citing Adobe’s investment in India for a very long time. “The White House did not roll out the red carpet for Modi and I don’t think this was an expectation on either side,” Mishra said. “More work needs to be done from both sides. However, in the meanwhile, trade and investments will continue to rise between private sectors from both countries. In addition, India will see more investments from other countries as well.”

Dinsha Mistree, fellow at the Hoover Institution and Stanford Law School, called Modi’s visit a promising start. “India and the US need to form a stronger relationship,” Mistree said. “On the matter of a trade agreement, there are still a multitude of issues that negotiators will have to get through. Also, both sides — and particularly leaders in the US — still have to vocalize support for an agreement. Not much will happen without that kind of buy-in. Hopefully the value of a trade deal will be recognized during Biden’s and Modi’s respective tenures.”

Mistree said that there were a number of sticky points. “If the agreement is being made on purely economic grounds, then the US is going to want access to industries that are heavily protected in India. Consider agriculture, for example. The US wants to sell agricultural goods in India, but Modi will find it difficult to open up agriculture to foreign competition,” he said. “One just has to look at the ongoing farmer protests from the recent attempts at domestic liberalization to realize how politically problematic such a move would be to allow outside competition.”

He added: “Also, don’t forget that there are upcoming state elections in Punjab and Uttar Pradesh in 2022. And apart from opening up traditionally protected markets, India will probably be pressed to change policy on various IP matters, and will have to address labor and environmental issues. “If, on the other hand, the US recognizes a security dimension or some other strategic interest in a trade agreement with India, then we might see a deal where India gains access to US markets without having to reciprocally open its own markets.”

He said India has been pushing for a preferential trade agreement for years, but under Biden it would only come as part of a broader security arrangement, if at all. “Personally speaking, I think that the US should agree to a preferential deal with India,” Mistree said. “What often gets lost among the quid-pro-quo aspects of these negotiations is the long-term value of bringing the US and India closer together. “Stronger trade relations could help both sides recognize our shared values and interests and might provide a springboard for working together on a number of other issues. Hopefully we will see some movement, but I fear we are still far away.”