The ancient Indian art of Kalamkari is finding new expression in Brooklyn, as young professionals engage with its techniques and storytelling traditions in a modern context.

In a bright Brooklyn apartment, young professionals gather around a large wooden table, immersing themselves in the art of Kalamkari, an ancient textile art form from rural Andhra Pradesh, India. Using natural dyes and bamboo pens, participants learn the traditional techniques that artisans have practiced for generations. This revival of Kalamkari—literally meaning “pen work”—is taking place in New York City, often led by individuals who previously had little exposure to its cultural roots.

Artist Nikita Shah, who has become a prominent Kalamkari teacher in New York, began her journey as a designer with Gaurang Shah, a luxury brand in India. Growing up surrounded by traditional crafts, she initially did not appreciate their significance. “People didn’t like Kalamkari as much as they do now,” she reflected, recalling her early experiences.

One of Shah’s notable projects is titled “At Home in Brooklyn.” This initiative involved months of workshops at the Brooklyn Community Pride Centre and GRIOT senior center, where over 30 participants, primarily from queer and marginalized communities, collaborated to create a communal Kalamkari story cloth. For Shah, this project symbolizes the essence of Kalamkari as a craft rooted in the narratives of those often unheard in society.

“It goes back to pre-colonial, pre-Hindu temple patronage,” Shah explained. “There have been histories of Kalamkari written by lower-class people, people who didn’t have a voice in society. I think about who the people are who don’t have a voice today, and how do we safeguard their stories.”

The artwork produced during this project was showcased at the Brooklyn Arts Council earlier this year. Shah noted that the practice of Kalamkari storytelling is becoming increasingly rare in India, with only a handful of artisans still using it as a medium for narrative expression.

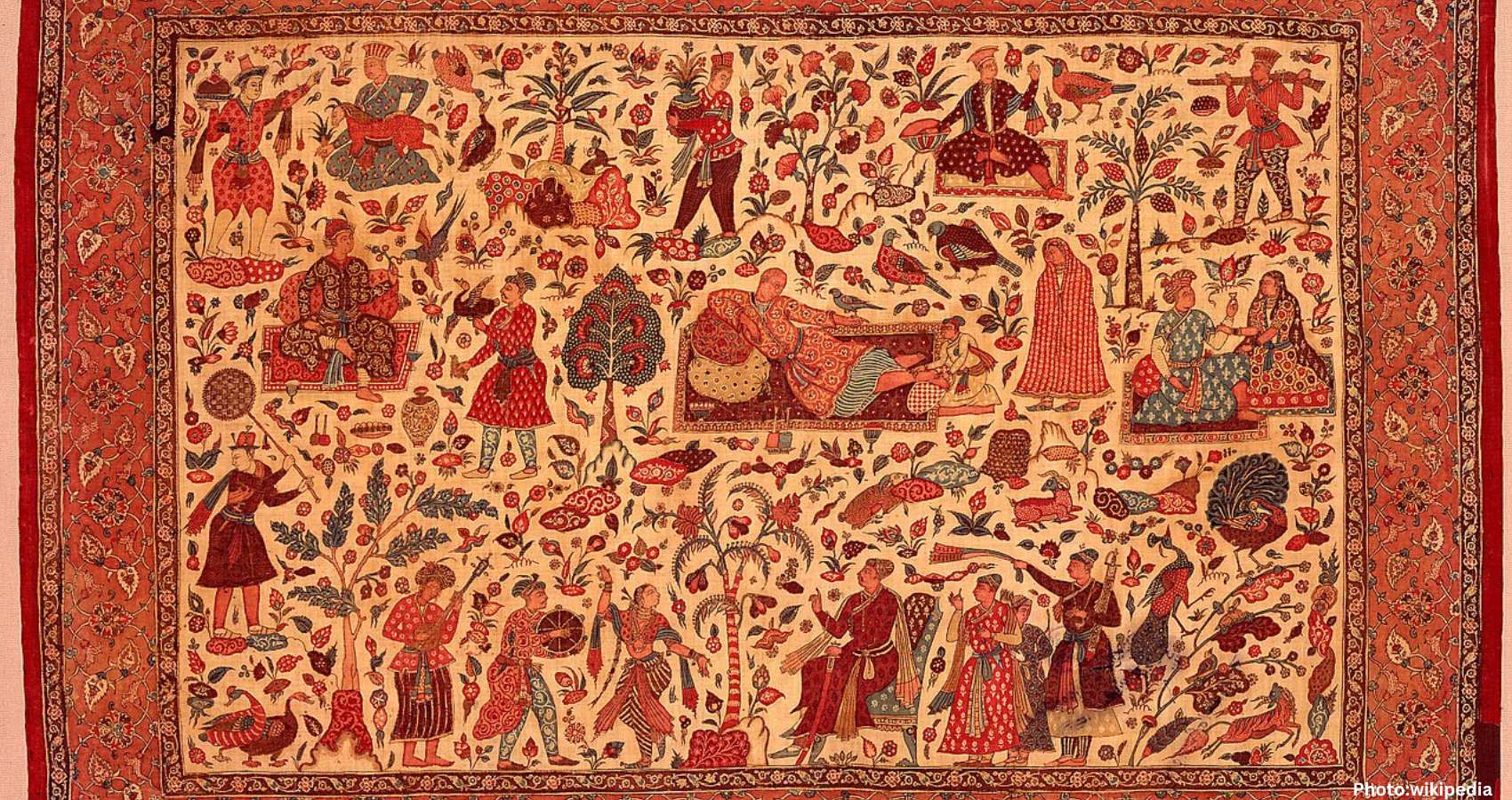

Kalamkari has roots that stretch back over 3,000 years to ancient India, where it emerged in villages known for their historic Hindu temples in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Initially, this art form served a spiritual purpose, with artisans depicting intricate narratives from Hindu epics on temple cloths and scrolls—sacred storytelling mediums that brought mythology to life.

Two distinct styles of Kalamkari evolved: Srikalahasti, characterized by freehand drawing with a kalam (bamboo pen), and Machilipatnam, which employs a block-printing technique. In the small town of Pedana, located in the Machilipatnam District of Andhra Pradesh, the process begins with handloomed cotton, which undergoes various natural treatments to enhance its colors and durability.

Shah’s apartment serves as both her home and art studio, filled with Kalamkari portraits of varying sizes. While the dyes and cloth reflect the traditional art form, the designs are personal and modern. Some pieces depict iconic New York imagery, such as the subway and the Statue of Liberty, while others feature intricate representations of the human form.

Working with traditional materials in New York presents unique challenges. Shah sources her bamboo pens and natural dyes from her mentor, Mamata Reddy, founder of KalamCreations in India, often paying above market rates to support the artisans. “For anything I buy from them, I pay 1.5 times the price,” she explained, emphasizing the importance of preserving this rare knowledge.

Her experience at Gaurang involved living with traditional weavers across India, allowing her to observe their techniques and understand the cultural significance embedded in textile making. “I learned not just the techniques but the traditions that go into textile making—knowledge that you’re not taught in design schools,” she noted.

After moving to New York in 2019 to pursue an associate’s degree in apparel design at the Fashion Institute of Technology, Shah discovered a community eager to learn about her cultural heritage. “I realized there was a gap—someone who had this kind of knowledge and people who were interested in learning it,” she said. This realization led her to conduct small-scale workshops in her home studio, designed to reflect the intimate atmosphere of weavers’ homes in India.

Shah later curated a semester-based workshop series called Fursat, a term used in South Asian languages to convey leisure, reflection, and wisdom. Through these workshops, participants not only learn Kalamkari techniques but also other forms of Indian textile arts, fostering a sense of community among attendees.

Fursat workshops are intimate, typically accommodating seven to eight participants. “It’s not a networking event,” Shah emphasized. “You’re here to build a connection.” Sukanya Prasad, a 26-year-old Tamil American and education manager at a Chelsea museum, was drawn to Shah’s workshops after relocating to New York in 2020. “I was craving more South Asian spaces,” she shared.

Prasad expressed her long-standing interest in Indian textiles and was excited to find an opportunity to learn Kalamkari without traveling to India. For Shah, Fursat provides attendees with a unique way to connect with their heritage, something often overlooked in traditional education.

The workshops encourage participants to explore their relationship with storytelling and the Kalamkari art form. Bhavika Yendapalli, 21, noted her struggle to relax and enjoy the process of art-making rather than focusing solely on the outcome. “We would find ourselves wanting to hang out and drink chai just like how our moms or grandmas did,” she said, highlighting the importance of shared experiences.

Shah begins each workshop with informal discussions, allowing participants to ease into the creative process. “You’re coming in and you’re showing up and you’re not starting on your piece right away,” Yendapalli explained. This approach fosters a relaxed atmosphere where attendees can connect over food and conversation.

Classes are scheduled for three hours but often extend well beyond that. “We would end up staying closer to almost midnight,” Prasad recalled, noting the organic flow of the sessions. This unhurried approach provided a grounding experience, particularly for those dealing with the stresses of daily life.

The slower pace of the workshops has led to lasting connections among participants. “We have a WhatsApp group chat,” Prasad mentioned, where attendees share events and support each other’s endeavors. Shah also organizes regular gatherings for workshop alumni, reinforcing the community bonds formed during the sessions.

Shah’s holistic approach to storytelling, community, and craft resonates deeply with participants. For Prasad, the supportive environment helped alleviate her perfectionism, allowing her to explore her creativity without fear of judgment.

Her final piece reflects the workshop’s philosophy, depicting her journey with Kalamkari through the lifecycle of a strawberry seed, culminating in a caricature of herself reaching for ripe fruit.

Yendapalli, who traveled to India to engage with Kalamkari artisans, noted a stark contrast in perceptions of the art form. “In New York, people are willing to appreciate and see the meaning behind it,” she observed, while some in India viewed it as merely commercial. Shah emphasized that many traditional Kalamkari producers have shifted their focus from storytelling to fashion, driven by economic pressures.

Despite these challenges, diasporic practitioners like Shah are playing a crucial role in preserving Kalamkari. By adapting the art for new contexts and communities, they ensure that its techniques and deeper wisdom continue to thrive in a fast-paced world.

Kalamkari art, once confined to the temples of India, is now evolving in Brooklyn, where it serves as a bridge between cultures and generations, fostering connections through the shared act of creation.

Source: Original article