Donald Trump stunned the political world in 2016 when he became the first person without government or military experience ever to be elected president of the United States. His four-year tenure in the White House revealed extraordinary fissures in American society but left little doubt that he is a figure unlike any other in the nation’s history.

Trump, the New York businessman and former reality TV show star, won the 2016 election after a campaign that defied norms and commanded public attention from the moment it began. His approach to governing was equally unconventional.

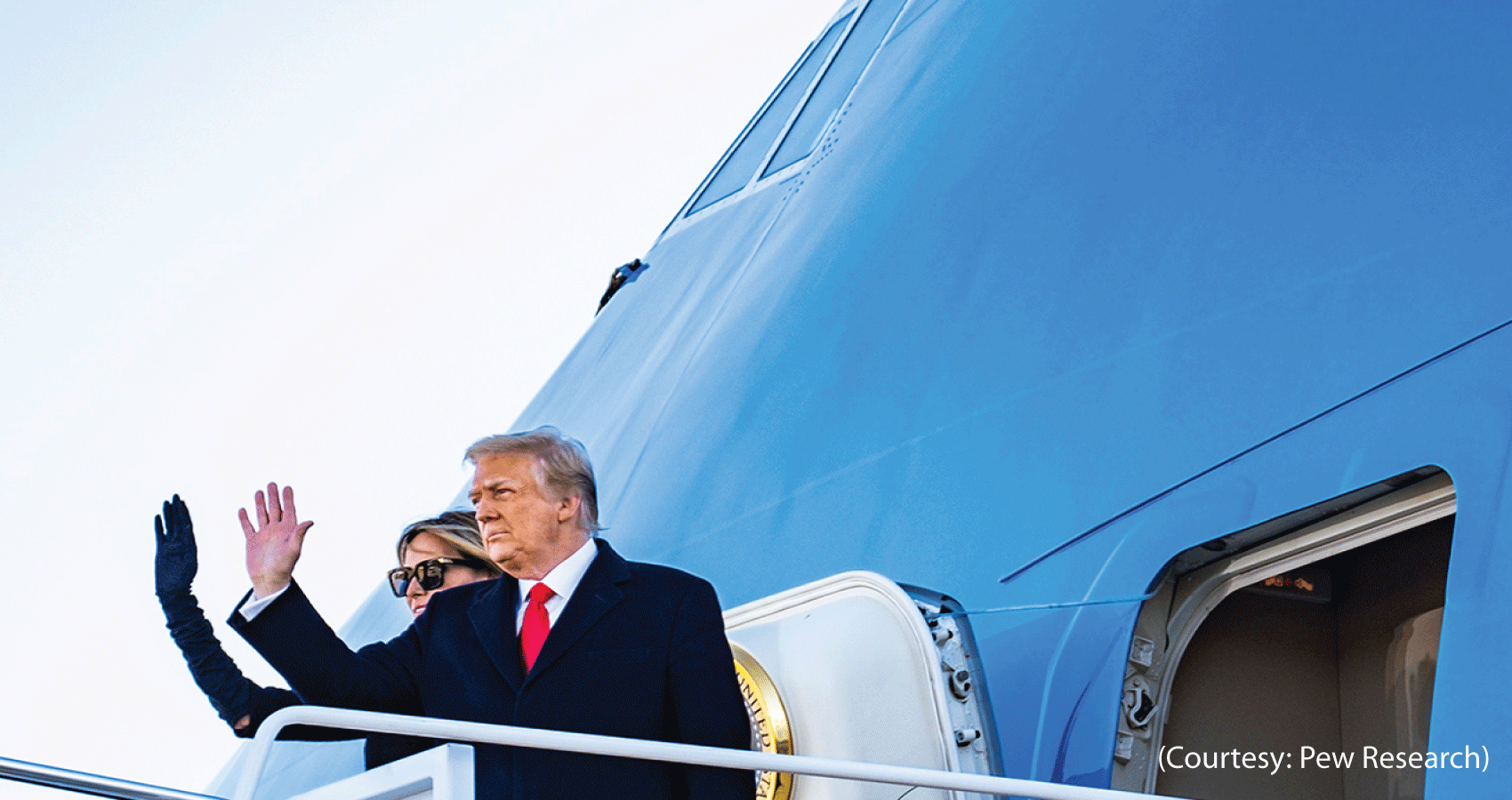

Other presidents tried to unify the nation after turning from the campaign trail to the White House. From his first days in Washington to his last, Trump seemed to revel in the political fight. He used his presidential megaphone to criticize a long list of perceived adversaries, from the news media to members of his own administration, elected officials in both political parties and foreign heads of state. The more than 26,000 tweets he sent as president provided an unvarnished, real-time account of his thinking on a broad spectrum of issues and eventually proved so provocative that Twitter permanently banned him from its platform. In his final days in office, Trump became the first president ever to be impeached twice – the second time for inciting an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol during the certification of the election he lost – and the nation’s first chief executive in more than 150 years to refuse to attend his successor’s inauguration.

Trump’s policy record included major changes at home and abroad. He achieved a string of long-sought conservative victories domestically, including the biggest corporate tax cuts on record, the elimination of scores of environmental regulations and a reshaping of the federal judiciary. In the international arena, he imposed tough new immigration restrictions, withdrew from several multilateral agreements, forged closer ties with Israel and launched a tit-for-tat trade dispute with China as part of a wider effort to address what he saw as glaring imbalances in America’s economic relationship with other countries.

Many questions about Trump’s legacy and his role in the nation’s political future will take time to answer. But some takeaways from his presidency are already clear from Pew Research Center’s studies in recent years. In this essay, we take a closer look at a few of the key societal shifts that accelerated – or emerged for the first time – during the tenure of the 45th president.

Deeply partisan and personal divides

Trump’s status as a political outsider, his outspoken nature and his willingness to upend past customs and expectations of presidential behavior made him a constant focus of public attention, as well as a source of deep partisan divisions.

Even before he took office, Trump divided Republicans and Democrats more than any incoming chief executive in the prior three decades.1 The gap only grew more pronounced after he became president. An average of 86% of Republicans approved of Trump’s handling of the job over the course of his tenure, compared with an average of just 6% of Democrats – the widest partisan gap in approval for any president in the modern era of polling.2 Trump’s overall approval rating never exceeded 50% and fell to a low of just 29% in his final weeks in office, shortly after a mob of his supporters attacked the Capitol.

Republicans and Democrats weren’t just divided over Trump’s handling of the job. They also interpreted many aspects of his character and personality in fundamentally opposite ways. In a 2019 survey, at least three-quarters of Republicans said the president’s words sometimes or often made them feel hopeful, entertained, informed, happy and proud. Even larger shares of Democrats said his words sometimes or often made them feel concerned, exhausted, angry, insulted and confused.

The strong reactions that Trump provoked appeared in highly personal contexts, too. In a 2019 survey, 71% of Democrats who were single and looking for a relationship said they would definitely or probably not consider being in a committed relationship with someone who had voted for Trump in 2016. That far exceeded the 47% of single-and-looking Republicans who said they would not consider being in a serious relationship with a Hillary Clinton voter.

Many Americans opted not to talk about Trump or politics at all. In 2019, almost half of U.S. adults (44%) said they wouldn’t feel comfortable talking about Trump with someone they didn’t know well. A similar share (45%) said later that year that they had stopped talking politics with someone because of something that person had said.

In addition to the intense divisions that emerged over Trump personally, his tenure saw a further widening of the gulf between Republicans and Democrats over core political values and issues, including in areas that weren’t especially partisan before his arrival.

In 1994, when Pew Research Center began asking Americans a series of 10 “values questions” on subjects including the role of government, environmental protection and national security, the average gap between Republicans and Democrats was 15 percentage points. By 2017, the first year of Trump’s presidency, the average partisan gap on those same questions had more than doubled to 36 points, the result of a steady, decades-long increase in polarization.

On some issues, there were bigger changes in thinking among Democrats than among Republicans during Trump’s presidency. That was especially the case on topics such as race and gender, which gained new attention amid the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements. In a 2020 survey that followed months of racial justice protests in the U.S., for instance, 70% of Democrats said it is “a lot more difficult” to be a Black person than to be a White person in the U.S. today, up from 53% who said the same thing just four years earlier. Republican attitudes on the same question changed little during that span, with only a small share agreeing with the Democratic view.

On other issues, attitudes changed more among Republicans than among Democrats. One notable example related to views of higher education: Between 2015 and 2017, the share of Republicans who said colleges and universities were having a negative effect on the way things were going in the U.S. rose from 37% to 58%, even as around seven-in-ten Democrats continued to say these institutions were having a positive effect.

One of the few things that Republicans and Democrats could agree on during Trump’s tenure is that they didn’t share the same set of facts. In a 2019 survey, around three-quarters of Americans (73%) said most Republican and Democratic voters disagreed not just over political plans and policies, but over “basic facts.”

Much of the disconnect between the parties involved the news media, which Trump routinely disparaged as “fake news” and the “enemy of the people.” Republicans, in particular, expressed widespread and growing distrust of the press. In a 2019 survey, Republicans voiced more distrust than trust in 2o of the 30 specific news outlets they were asked about, even as Democrats expressed more trust than distrust in 22 of those same outlets. Republicans overwhelmingly turned to and trusted one outlet included in the study – Fox News – even as Democrats used and expressed trust in a wider range of sources. The study concluded that the two sides placed their trust in “two nearly inverse media environments.”

Some of the media organizations Trump criticized most vocally saw the biggest increases in GOP distrust over time. The share of Republicans who said they distrusted CNN rose from 33% in a 2014 survey to 58% by 2019. The proportion of Republicans who said they distrusted The Washington Post and The New York Times rose 17 and 12 percentage points, respectively, during that span.3

In addition to their criticisms of specific news outlets, Republicans also questioned the broader motives of the media. In surveys fielded over the course of 2018 and 2019, Republicans were far less likely than Democrats to say that journalists act in the best interests of the public, have high ethical standards, prevent political leaders from doing things they shouldn’t and deal fairly with all sides. Trump’s staunchest GOP supporters often had the most negative views: Republicans who strongly approved of Trump, for example, were much more likely than those who only somewhat approved or disapproved of him to say journalists have very low ethical standards.

Apart from the growing partisan polarization over the news media, Trump’s time in office also saw the emergence of misinformation as a concerning new reality for many Americans. Half of U.S. adults said in 2019 that made-up news and information was a very big problem in the country, exceeding the shares who said the same thing about racism, illegal immigration, terrorism and sexism. Around two-thirds said made-up news and information had a big impact on public confidence in the government (68%), while half or more said it had a major effect on Americans’ confidence in each other (54%) and political leaders’ ability to get work done (51%).

Misinformation played an important role in both the coronavirus pandemic and the 2020 presidential election. Almost two-thirds of U.S. adults (64%) said in April 2020 that they had seen at least some made-up news and information about the pandemic, with around half (49%) saying this kind of misinformation had caused a great deal of confusion over the basic facts of the outbreak. In a survey in mid-November 2020, six-in-ten adults said made-up news and information had played a major role in the just-concluded election.

Conspiracy theories were an especially salient form of misinformation during Trump’s tenure, in many cases amplified by the president himself. For example, nearly half of Americans (47%) said in September 2020 that they had heard or read a lot or a little about the collection of conspiracy theories known as QAnon, up from 23% earlier in the year.4 Most of those aware of QAnon said Trump seemed to support the theory’s promoters.

Trump frequently made disproven or questionable claims as president. News and fact-checking organizations documented thousands of his false statements over four years, on subjects ranging from the coronavirus to the economy. Perhaps none were more consequential than his repeated assertion of widespread fraud in the 2020 election he lost to Democrat Joe Biden. Even after courts around the country had rejected the claim and all 50 states had certified their results, Trump continued to say he had won a “landslide” victory. The false claim gained widespread currency among his voters: In a January 2021 survey, three-quarters of Trump supporters incorrectly said he was definitely or probably the rightful winner of the election.

New concerns over American democracy

Throughout his tenure, Donald Trump questioned the legitimacy of democratic institutions, from the free press to the federal judiciary and the electoral process itself. In surveys conducted between 2016 and 2019, more than half of Americans said Trump had little or no respect for the nation’s democratic institutions and traditions, though these views, too, split sharply along partisan lines.

The 2020 election brought concerns about democracy into much starker relief. Even before the election, Trump had cast doubt on the security of mail-in voting and refused to commit to a peaceful transfer of power in the event that he lost. When he did lose, he refused to publicly concede defeat, his campaign and allies filed dozens of unsuccessful lawsuits to challenge the results and Trump personally pressured state government officials to retroactively tilt the outcome in his favor.

The weeks of legal and political challenges culminated on Jan. 6, 2021, when Trump addressed a crowd of supporters at a rally outside the White House and again falsely claimed the election had been “stolen.” With Congress meeting the same day to certify Biden’s win, Trump supporters stormed the Capitol in an attack that left five people dead and forced lawmakers to be evacuated until order could be restored and the certification could be completed. The House of Representatives impeached Trump a week later on a charge of inciting the violence, with 10 Republicans joining 222 Democrats in support of the decision.

Most Americans placed at least some blame on Trump for the riot at the Capitol, including 52% who said he bore a lot of responsibility for it. Again, however, partisans’ views differed widely: 81% of Democrats said Trump bore a lot of responsibility, compared with just 18% of Republicans.

Even as he repeatedly cast doubt on the democratic process, Trump proved to be an enormously galvanizing figure at the polls. Nearly 160 million Americans voted in 2020, the highest estimated turnout rate among eligible voters in 120 years, despite widespread changes in voting procedures brought on by the pandemic. Biden received more than 81 million votes and Trump received more than 74 million, the highest and second-highest totals in U.S. history. Turnout in the 2018 midterm election, the first after Trump took office, also set a modern-day record.

Pew Research Center surveys catalogued the high stakes that voters perceived, particularly in the run-up to the 2020 election. Just before the election, around nine-in-ten Trump and Biden supporters said there would be “lasting harm” to the nation if the other candidate won, and around eight-in-ten in each group said they disagreed with the other side not just on political priorities, but on “core American values and goals.”

Earlier in the year, 83% of registered voters said it “really mattered” who won the election, the highest percentage for any presidential election in at least two decades. Trump himself was a clear motivating factor for voters on both sides: 71% of Trump supporters said before the election that their choice was more of a vote for the president than against Biden, while 63% of Biden supporters said their choice was more of a vote against Trump than for his opponent.

A reckoning over racial inequality

Racial tensions were a constant undercurrent during Trump’s presidency, often intensified by the public statements he made in response to high-profile incidents.

The death of George Floyd, in particular, brought race to the surface in a way that few other recent events have. The videotaped killing of the unarmed, 46-year-old Black man by a White police officer in Minneapolis was among several police killings that sparked national and international protests in 2020 and led to an outpouring of public support for the Black Lives Matter movement, including from corporations, universities and other institutions. In a survey shortly after Floyd’s death in May, two-thirds of U.S. adults – including majorities across all major racial and ethnic groups – voiced support for the movement, and use of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag surged to a record high on Twitter.

Attitudes began to change as the protests wore on and sometimes turned violent, drawing sharp condemnation from Trump. By September, support for the Black Lives Matter movement had slipped to 55% – largely due to decreases among White adults – and many Americans questioned whether the nation’s renewed focus on race would lead to changes to address racial inequality or improve the lives of Black people.

Race-related tensions erupted into public view earlier in Trump’s tenure, too. In 2017, White nationalists rallied in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of a Confederate statue amid a broader push to eliminate such memorials from public spaces across the country. The rally led to violent clashes in the city’s streets and the death of a 32-year-old woman when a White nationalist deliberately drove a car into a crowd of people. Tensions also arose in the National Football League as some players protested racial injustices in the U.S. by kneeling during the national anthem. The display prompted a backlash among some who saw it as disrespectful to the American flag.

In all of these controversies and others, Trump weighed in from the White House, but typically not in a way that most Americans saw as helpful. In a summer 2020 survey, for example, six-in-ten U.S. adults said Trump had delivered the wrong message in response to the protests over Floyd’s killing. That included around four-in-ten adults (39%) who said Trump had delivered the completely wrong message.

More broadly, Americans viewed Trump’s impact on race relations as far more negative than positive. In an early 2019 poll, 56% of adults said Trump had made race relations worse since taking office, compared with only 15% who said he had made progress toward improving relations. In the same survey, around two-thirds of adults (65%) said it had become more common for people in the U.S. to express racist or racially insensitive views since his election.

The public also perceived Trump as too close with White nationalist groups. In 2019, a majority of adults (56%) said he had done too little to distance himself from these groups, while 29% said he had done about the right amount and 7% said he had done too much. These opinions were nearly the same as in December 2016, before he took office.

While Americans overall gave Trump much more negative than positive marks for his handling of race relations, there were consistent divisions along racial, ethnic and partisan lines. Black, Hispanic and Asian adults were often more critical of Trump’s impact on race relations than White adults, as were Democrats when compared with Republicans. For example, while an overwhelming majority of Democrats (83%) said in 2019 that Trump had done too little to distance himself from White nationalist groups, a majority of Republicans (56%) said he had done about the right amount.

White Republicans, in particular, rejected the idea of widespread structural racism in the U.S. and saw too much emphasis on race. In September 2020, around eight-in-ten White Republicans (79%) said the bigger problem was people seeing racial discrimination where it doesn’t exist, rather than people not seeing discrimination where it really does exist. The opinions of White Democrats on the same question were nearly the reverse.

A defining public health and economic crisis

Every presidency is shaped by outside events, and Trump’s will undoubtedly be remembered for the enormous toll the coronavirus pandemic took on the nation’s public health and economy.

More than 400,000 Americans died from COVID-19 between the beginning of the pandemic and when Trump left office, with fatality counts sometimes exceeding 4,000 people a day – a toll more severe than the overall toll of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, or the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Trump himself contracted the coronavirus in the home stretch of his campaign for reelection, as did dozens of White House and campaign staff and members of his family.

The far-reaching public health effects of the virus were reflected in a survey in November 2020, when more than half of U.S. adults (54%) said they personally knew someone who had been hospitalized or died due to COVID-19. The shares were even higher among Black (71%) and Hispanic (61%) adults.

Nurses and health care workers mourn and remember colleagues who had died of COVID-19 outside Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan in April 2020. (Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images)

At the same time, the pandemic had a disastrous effect on the economy. Trump and Barack Obama together had presided over the longest economic expansion in American history, with the U.S. unemployment rate at a 50-year low of 3.5% as recently as February 2020. By April 2020, with businesses around the country closing their doors to prevent the spread of the virus, unemployment had soared to a post-World War II high of 14.8%. Even after considerable employment gains later in the year, Trump was the first modern president to leave the White House with fewer jobs in the U.S. than when he took office.

The economic consequences of the virus, like its public health repercussions, hit some Americans harder than others. Many upper-income workers were able to continue doing their jobs remotely during the outbreak, even as lower-income workers suffered widespread job losses and pay cuts. The remarkable resiliency of U.S. stock markets was a rare bright spot during the downturn, but one that had its own implications for economic inequality: Going into the outbreak, upper-income adults were far more likely than lower-income adults to be invested in the market.

The pandemic clearly underscored and exacerbated America’s partisan divisions. Democrats were consistently much more likely than Republicans to see the virus as a major threat to public health, while Republicans were far more likely than Democrats to see it as exaggerated and overblown. The two sides disagreed on public health strategies ranging from mask wearing to contact tracing.

The outbreak also had important consequences for America’s image in the world. International views of the U.S. had already plummeted after Trump took office in 2017, but attitudes turned even more negative amid a widespread perception that the U.S. had mishandled the initial outbreak. The share of people with a favorable opinion of the U.S. fell in 2020 to record or near-record lows in Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and other countries. Across all 13 nations surveyed, a median of just 15% of adults said the U.S. had done a good job responding to COVID-19, well below the median share who said the same thing about their own country, the World Health Organization, the European Union and China.

At a much more personal level, many Americans expected the coronavirus outbreak to have a lasting impact on them. In an August 2020 survey, 51% of U.S. adults said they expected their lives to remain changed in major ways even after the pandemic is over.

Looking ahead

The aftershocks of Donald Trump’s one-of-a-kind presidency will take years to place into full historical context. It remains to be seen, for example, whether his disruptive brand of politics will be adopted by other candidates for office in the U.S., whether other politicians can activate the same coalition of voters he energized and whether his positions on free trade, immigration and other issues will be reflected in government policy in the years to come.

Some of the most pressing questions, particularly in the aftermath of the attack on the Capitol and Trump’s subsequent bipartisan impeachment, concern the future of the Republican Party. Some Republicans have moved away from Trump, but many others have continued to fight on his behalf, including by voting to reject the electoral votes of two states won by Biden.

The GOP’s direction could depend to a considerable degree on what Trump does next. Around two-thirds of Americans (68%) said in January 2021 that they would not like to see Trump continue to be a major political figure in the years to come, but Republicans were divided by ideology. More than half of self-described moderate and liberal Republicans (56%) said they preferred for him to exit the political stage, while 68% of conservatives said they wanted him to remain a national political figure for many years to come.

Joe Biden, newly sworn in as the 46th president, signs documents at the U.S. Capitol formalizing his Cabinet and sub-Cabinet nominations on Jan. 20, 2021. (Jim Lo Scalzo/Pool/AFP via Getty Images)

For his part, Joe Biden has some advantages as he begins his tenure. Democrats have majorities – albeit extraordinarily narrow ones – in both legislative chambers of Congress. Other recent periods of single-party control in Washington have resulted in the enactment of major legislation, such as the $1.5 trillion tax cut package that Trump signed in 2017 or the health care overhaul that Obama signed in 2010. Biden begins his presidency with generally positive assessments from the American public about his Cabinet appointments and the job he has done explaining his policies and plans for the future. Early surveys show that he inspires broad confidence among people in three European countries that have long been important American allies: France, Germany and the UK.

Still, the new administration faces obvious challenges on many fronts. The coronavirus pandemic will continue in the months ahead as the vast majority of Americans remain unvaccinated. The economy is likely to struggle until the outbreak is under control. Polarization in the U.S. is not likely to change dramatically, nor is the partisan gulf in views of the news media or the spread of misinformation in the age of social media. The global challenges of climate change and nuclear proliferation remain stark.

The nation’s 46th president has vowed to unite the country as he moves forward with his policy agenda. Few would question the formidable nature of the task.

(Courtesy: Pew Research)