America’s population size is standing still, according to new data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Population growth over the 12-month period from July 1, 2020 through July 1, 2021 stood at unprecedented low of just 0.12%. This is the lowest annual growth since the Bureau began collecting such statistics in 1900, and reflects how all components of population change—deaths, births, and immigration levels—were impacted during a period when the COVID-19 pandemic became most prevalent.[i]

The new estimates show that during this period, population growth declined from the previous year in 31 of 50 states as well as Washington, D.C., with 18 states sustaining absolute population losses. In some states, especially California and New York, population losses were exacerbated by inflated out-migration during the pandemic, just as other states such as Florida and Texas benefitted from greater population in-flows.

While COVID-19 clearly played a role in this near-zero population growth, that growth had begun to plummet even before the pandemic. The 2020 census showed that from 2010 to 2020, the U.S. registered the second-lowest decade growth in its history—a consequence, in large part, of the aging of its population, which led to more deaths and fewer births. Nonetheless, the new data shows that pandemic-related demographic forces have left an indelible mark on the nation.

Historic dips and spikes in population growth follow pandemics and economic trends

The unprecedented near cessation of U.S. population growth is depicted in Figure 1, which charts annual growth rates in the 121-year period from 1900 to 2021. Over this time, the nation experienced wide variations in growth, resulting from wars, economic booms and busts, as well as changing fertility and immigration patterns.

The unprecedented near cessation of U.S. population growth is depicted in Figure 1, which charts annual growth rates in the 121-year period from 1900 to 2021. Over this time, the nation experienced wide variations in growth, resulting from wars, economic booms and busts, as well as changing fertility and immigration patterns.

Noteworthy are the sharp dips in growth: in 1918-19, due largely to the Spanish Flu pandemic, and in the late 1920s and early 1930s as a result of the Great Depression. Growth rose to levels approaching 2% during the prosperous post-World War II “baby boom” years of the 1950s and 1960s. And after a lull in the 1970s and 1980s, population growth rose again in the 1990s due to rising immigration and millennial generation births.

The 21st century ushered in another population growth downturn, exacerbated by the 2007-09 Great Recession. This spilled into a 2010s decade-wide growth slowdown that provided a backdrop for the nearly flat growth of 0.12% in 2020-21. This most recent statistic reflects more deaths and fewer births associated with an aging population along with greater restrictions in immigration near the end of the decade, even before the pandemic hit.

The factors that led to today’s unprecedented flat growth rate

The demographic components of reduced population growth in 2020-21 are depicted in Figure 2, which contrasts year-by-year changes since 2000 in what demographers call “natural increase”—the excess of births over deaths as well as net international migration.

As indicted above, declines in the nation’s natural increase levels during the 2010s reflected more deaths associated with an aging population as well as the after-effects of the Great Recession in the postponement of childbearing for young adult women. Immigration trends were more uneven due to changing economic circumstances, including the recession and immediate post-recession downturn, as well as immigration policies that became more restrictive during the Trump administration.

Both natural increase and immigration contributions to population growth became markedly reduced in 2020-21, in large part due to the pandemic. (Pandemic impacts were partially evident already in 2019-20 data.) Population gains attributable to natural increase rose as high as 1.1 million in 2016-17, but dropped to 677,000 in 2019-20 and then again to 148,000 in 2020-21. Over the past two years, the number of deaths in the U.S. rose by 363,000 (from 3.07 million to 3.43 million) and the number of births declined by 166,000 (from 3.74 million to 3.58 million)—reflecting, in part, pandemic-related decisions to postpone having children.

Immigration levels plummeted as well, exacerbating the impacts of earlier policy restrictions. The new estimates showed a net international migration of just 256,000 in 2020-21—down from an already low 477,000 in 2019-20 and from over 1 million per year in the middle of the 2010s decade.

Despite this decline in immigration, it was the dip in natural increase—propelled by deaths during the pandemic—that drove much of the nation’s dramatic growth slowdown. In contrast to earlier years, the contribution of natural increase to the nation’s growth was even less than that of immigration.

Eighteen states lost population in the past year

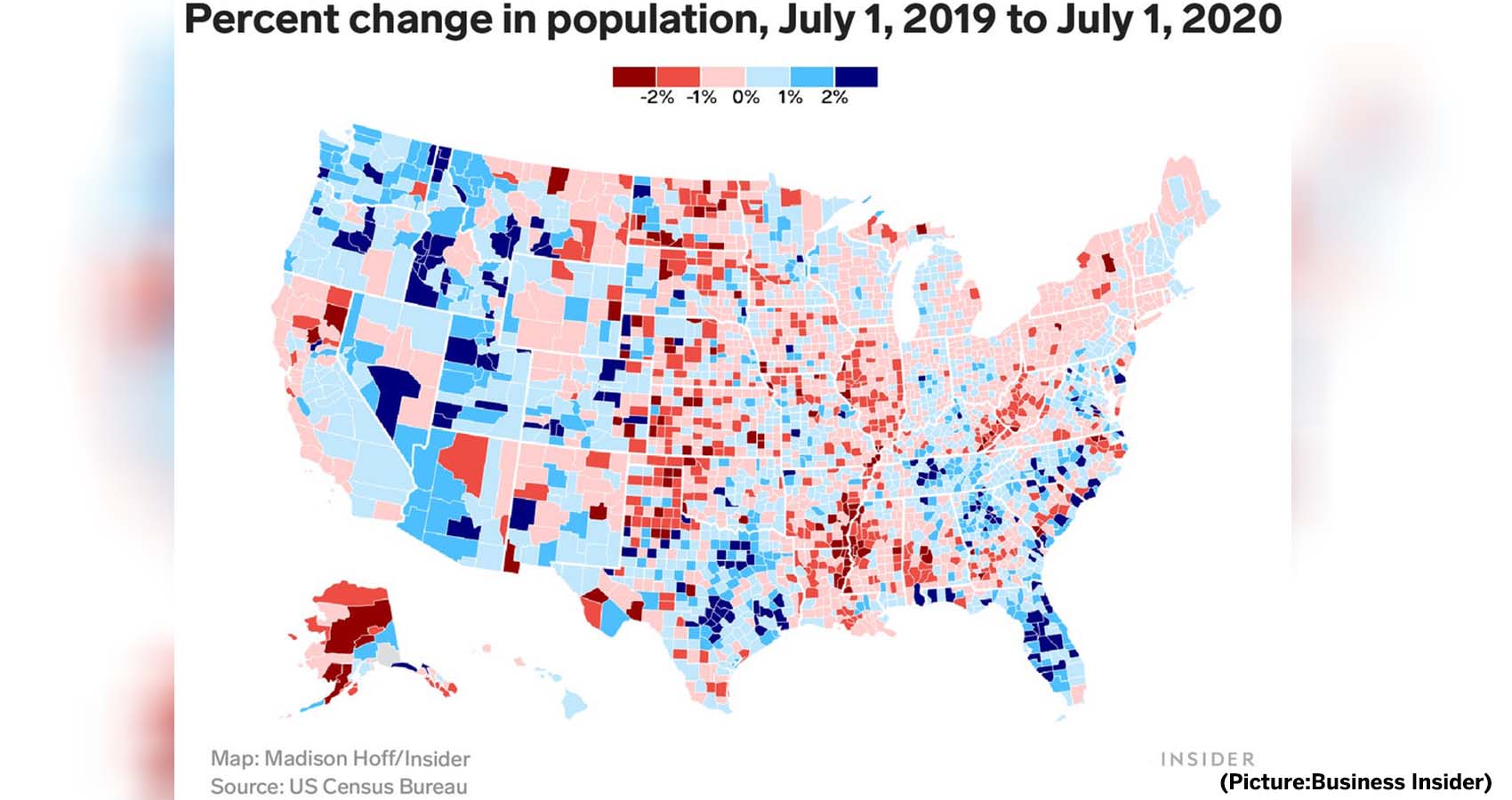

The national growth slowdown exerted a broad impact across the nation’s states. Among the nation’s 50 states and Washington, D.C., 31 showed lower growth (or greater losses) in 2020-21 than in 2019-20 (see downloadable Table B).

The states that led in growth rates were mostly in the Mountain West, including Idaho, Utah, Montana, and Arizona, which had annual rates exceeding 1.4%. In terms of numeric growth, the biggest gainers in 2020-21 were Texas (310,000 people), Florida (211,000), Arizona (98,000), and North Carolina (93,000). Still, these gains were smaller than what these states saw in 2019-20 or 2018-19.

Perhaps most noteworthy is the fact that 18 states (including Washington, D.C.) lost population in 2020-21. This is up from 16 population-losing states 2019-20; 14 in 2018-19; and just 10 in the two prior years.

New York and California registered the biggest numeric losses. Both states showed substantially greater losses in 2020-21 than in the prior two years, as was the case for most states that sustained recent population losses.

Twenty-five states registered more deaths than births

The poor growth performance of most states in 2020-21 reflects a combination of lower natural increase and smaller immigration from abroad—components which led to reduced national growth and reduced domestic migration across states (see downloadable Table C).

All 50 states and Washington, D.C. displayed lower natural increase in 2020-21 than in the previous year. Moreover, 25 states showed what demographers call “natural decrease”—an excess of deaths over births. Led by Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and West Virginia, most of these states are in the nation’s Northeast, Midwest, and Southeast. Just eight of these states registered natural decreases in 2019-20; in 2018-19, this was the case for only four (West Virginia, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont).

Similarly, immigration from abroad was lower across all 50 states and Washington, D.C. in 2020-21 than in the previous year. This is especially the case for those with greatest immigrant gains: Florida, Texas, New York, and California.

Domestic migration sharpened state gains and losses

Domestic migration (movement within the U.S.) is the one demographic component which can either worsen or improve state population growth in a slow growth environment. This was especially the case during the past year, when pandemic-related economic, social, and safety factors prompted selective movement flows.

The new census estimates show how domestic migration impacted states which both lost and gained population. For example, the three states with the greatest overall population losses—New York, California, and Illinois—were the three leaders in net out-migration. These states contain major cities and metropolitan areas, which have been associated with out-migration during the pandemic, and registered greater out-migration in 2020-21 than in each of the previous two years. It is also noteworthy that Washington, D.C. lost 23,000 domestic migrants—a huge outlier from earlier years, when the city experienced far smaller migration losses or gains (see downloadable Table C).

Similarly, states with the greatest overall population gains—Texas, Florida, and Arizona—were leaders in 2020-21 domestic in-migration. Just as most migrant-losing states shed greater numbers of migrants during the pandemic than earlier, it is the case that most migrant-gaining states (Arizona and Nevada were among the exceptions) gained more migrants than before.

A historic demographic low point

Among the many consequences the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted on the nation, its impact on the nation’s demographic stagnation is likely to be consequential. The new census estimates make plain that as a result of more deaths, fewer births, and a recent low in immigration, America has achieved something close to zero growth in the 2020-21 period. This trend has affected most states, and will lead to sharp changes in how many Americans make decisions about childbearing as well as where and how they live.

While it is true that the rise in pandemic-period deaths—especially among the older population—contributed much to this slow growth, declines in fertility and immigration also added a great deal. Because the latter demographic components contribute most to any future rise in the nation’s youth and labor-force-age population, it is vital that we examine public policies that can overcome barriers to the bearing and raising of children and, probably most important, stimulate immigration in ways that will reinvigorate the nation’s population growth.

Even before the onset of the pandemic, Census Bureau projections foresaw the onset of slower growth, increased aging, and continued stagnation of our labor force. Among the many ways that are needed to recover from the pandemic, a focus on reactivating the nation’s population growth should be given high priority.