Pummeled by the pandemic, at least 40% of rural U.S. hospitals are in danger of shutting down and leaving millions of people in smaller and less affluent communities without a nearby emergency and critical care facility.

That’s the conclusion of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, whose recent study sees 500 hospitals at immediate risk for closing within two years and more than 300 others at high risk within five years. The grim assessment by the policy center found the problems spread across the country, and that the threats will persist even if the pandemic ends because rising costs are outrunning revenue.

All told, there are about 38 million Americans in the at-risk areas; they’d have to drive at least 20 minutes farther if their local hospitals close, with half adding at least 30 minutes, said Harold Miller, the center’s chief executive and author of the report. Many of the facilities are in sparsely populated but important farming, mining or ranching communities.

Hospital Emergency

Negative margins are putting smaller hospitals at high risk of failure

“The myth is that these are hospitals that should no longer exist in communities that should no longer exist,” Miller said in an interview. Keeping those facilities open would cost $3.4 billion, or less than 1% of total annual spending on hospitals, said Miller, an adjunct public policy and management professor and former associate dean at Carnegie Mellon University.

“The myth is that these are hospitals that should no longer exist in communities that should no longer exist,” Miller said in an interview. Keeping those facilities open would cost $3.4 billion, or less than 1% of total annual spending on hospitals, said Miller, an adjunct public policy and management professor and former associate dean at Carnegie Mellon University.

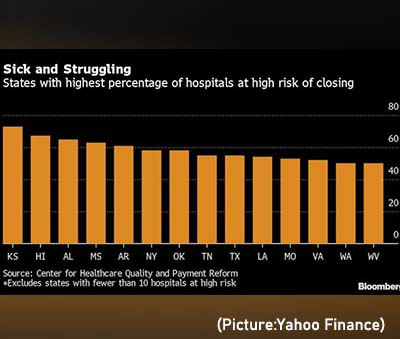

Fifteen states have more than half of their rural hospitals at risk of closing because of persistent losses, including Texas and a large swath of the South and Midwest such as Kansas and Mississippi, the study shows. But rural hospitals in New York, Connecticut and Washington State are also in trouble.

More than 130 rural hospitals have closed in the last decade, according to the University of North Carolina’s Sheps Center, and they’re often the only option for health care in their communities.

Higher costs for labor and supplies and lower revenue have trounced hospitals as they shut down elective procedures to care for critically ill Covid-19 patients. Even with billions in federal money, operating margins at U.S. hospitals were negative 3.3% in January, health-care consultancy Kaufman Hall said, and that’s including the strongest operators. Meanwhile, they’re facing pending cuts in Medicare payments along with repayments of funds advanced earlier in the pandemic.

Sick and Struggling: States with highest percentage of hospitals at high risk of closing

What’s really hurting the smaller providers, Miller said, is a longstanding inability to negotiate the same rates as their larger counterparts for the roughly half of their patients who have private insurance. Bigger facilities rely on higher payments from private insurers to offset lower reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid. On top of that, the sparser populations mean costs per patient are higher so the hospitals can’t always count on a flow of patients to finance essential services like emergency care.

“The problem is, they don’t get paid if you don’t go,” Miller said. This means that state and local governments — and their taxpayers — pick up more of the tab, he said. His research shows margins declining with hospital size.

A representative for health-insurance trade group AHIP didn’t provide an immediate comment.

Emergency Rooms

Some rural hospitals do get federal reimbursements that cover their costs, and a new program that takes effect next year will increase payments to qualifying facilities that eliminate in-patient beds, which often sit empty. But Miller said most of the hospitals aren’t losing money on in-patient services, but rather on their emergency rooms and clinics.

Increasing payments can help, but the system also needs more coordinated planning to ensure all communities have care, said Kenneth Kaufman, Kaufman Hall’s chair. “We have a reimbursement problem of course, but we also have a structural problem,” he said in an interview. “There’s just not enough patients to sustain a lot of these hospitals.”

A handful of states like California are experimenting with different methods of financing struggling hospitals, Kaufman said. “There’s nothing likely to get done at the federal level.”

The hospital study examined finances over a three-year period using publicly available data and didn’t rely on commercial funding, according to Miller. Miller suggests that insurers fund rural hospitals through monthly payments in addition to reimbursement for services in a manner similar to other public services. “We don’t pay the fire department based on the fire,” he said.